Anak Tomb No. 3

| Anak Tomb No. 3 | |

| |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 안악삼호무덤 |

| Hancha | 安岳三號墳 |

| Revised Romanization | Anak-samho-mudeom |

| McCune–Reischauer | Anak-samho-mudŏm |

Anak Tomb No. 3 is a chamber tomb of Goguryeo located in Anak, South Hwanghae, North Korea. It is known for mural paintings and an epitaph. It is part of the Complex of Koguryo Tombs.

It was discovered in 1949 with valuable treasures stolen, but murals in good condition.

Epitaph and its interpretation

[edit]The Anak Tomb No.3 is one of few Goguryeo tombs that have epitaphs so that their dates can be determined. Its seven-lined epitaph contains the date 357, the personal name Dong Shou (冬壽), his title, his birthplace and his age at death.[1] Accordingly, some scholars generally regard this site as the tomb of Dong Shou.[1][2] The inscription of Dong Shou relates that he was a general from the Xianbei state of Former Yan in Liaodong (modern Liaoning, China), who fled to Goguryeo in 336 and was given a position in the former territory of the Lelang commandery.[3] Chinese scholar Yeh Pai who deciphered the inscription in 1951 and published his findings in North Korea's Institute of Archeology report and argued that the man was the same Dong Shou, a refugee from Liaodong who fled the Xianbei invasions in 337, as the one who appeared in two Chinese histories, the Chin shu and Tzu-chih t'ung-chien.[2] Yeh Pai's conclusions were accepted in the 1958 formal Korean report; however some Korean scholars still maintained that the tomb belongs to King Mi-chon.[2] While K. H. J. Gardiner and Wonyong Kim believe this to be a Chinese tomb of excellent quality, North and other South Korean scholars believe that Dong Shou was an emigre official. Moreover, the quality of these paintings and the size of the tomb indicate that it is a royal tomb of Koguryo—a theory advocated recently by Hwi-joon Ahn and Youngsook Pak.[3] North Korean scholars claim that it is the mausoleum of King Micheon or King Gogugwon.

The epitaph reflects a complex situation in which Dong Shou, and Goguryeo, were put. He claimed various titles including "Minister of Lelang" and "Governor of Changli, Xuantu and Daifang." It is not clear whether these titles were given by the Eastern Jin or just self-designation. Scholars associate one of his title "Minister of Lelang" with the title "Duke of Lelang", which was bestowed on King Gogugwon by Murong Jun of the Former Yan in 354.

Murals

[edit]-

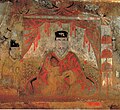

Man (owner of the tomb)

-

Woman (wife of the owner)

-

Procession Scene

-

Indoor Life Painting

The Anak Tomb No. 3 is the host to multiple famous mural paintings, each giving a greater insight to the life and hierarchy of the Goguryeo people.[4] It contains two portraits, one on the front wall of the west side chamber and one on the southern wall, portraying a man and a woman, respectively.[4] Scholars have disputed the owner of this tomb and thus the identity of people portrayed in these murals; because of the epitaph, many believe that the images depict Dong Shou, a refugee from Former Yan, and his wife, while others believe that the person depicted was the Goguryeo king, King Gogukwon.[4][5] The man in the mural is shown to be sitting upright and is flanked by other men who are smaller than him. He is dressed in red silk clothes with a white kwan[6] over a black inner kwan [4] and is staring straight out with an impersonal expression.[5] The painting of the woman resides on the southern wall of the tomb, next to that of the man, and her sitting position is slightly turned in to face him.[4] The woman also wears an impersonal expression, but with a notable face shape; her face, as well as the faces of the women who flank her, is round and full, different from the typical facial structure of the Goguryeo people, who had long and oval faces.[5] The woman is however wearing Chinese set of attire called guiyi, which is a multi-lap swallow-tail clothing;[7][8] this reflects Chinese influences in the tomb and may indicate the clothing style worn in the Chinese six dynasties.[3] The woman's hairstyle is identical to the hairstyle in Northern Wei.[8]

The next mural in this tomb is a procession scene and resides in the corridor. It contains 250 people, including the owner of the tomb who is sitting in a cow-pulled wagon.[4] Other Goguryeo people displayed in this mural include members of a marching band, flag bearers, maids and civil officials.[4] The large number of people suggests the high social status of the owner.[4] It is also important to note the seemingly identical, impersonal facial structure of the people included in this scene. This can be attributed to the fact that at the time when this mural was developed, the expression of individuality was not yet a developed technique in Goguryeo paintings.[5]

The inside of the eastern chamber contains a colorful mural illustrating the typical life of the Goguryeo people. The scene includes a kitchen, a meat storage room, a barn, a carriage shed, and household staff, along with other commonplace features.[4][5] This mural allows scholars to analyze the daily rituals of the Goguryeo culture, and gain insight on what the house of the tomb's owner may have looked like.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "冬壽墓蓮花紋研究" Archived January 13, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c John Whitney Hall; et al., eds. (1988–1999). The Cambridge history of Japan. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 300. ISBN 0-521-22352-0. OCLC 17483588.

- ^ a b c Junghee Lee. "The Evolution of Koguryo Tomb Murals". Buddhapia. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i http://contents.nahf.or.kr/goguryeo/anak3/an_html_en/int1.html%7Ctitle=contents.nahf.or.kr/goguryeo/anak3/an_html_en/int1.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Jeon, Ho-Tae. Artistic Creation, Borrowing, Adaptation, and Assimilation in Koguryǒ Tomb Murals of the Fourth to Seventh Century. Duke University Press.

- ^ "Kwan | The World of Hat Museum in Riga, Latvia". worldhat.net. Archived from the original on 2018-01-14. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- ^ Xun Zhou; Chunming Gao (1987). 5000 years of Chinese costumes. San Francisco, CA: China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 0-8351-1822-3. OCLC 19814728.

- ^ a b Chung, Young Yang (2005). Silken threads : a history of embroidery in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. New York: H.N. Abrams. p. 294. ISBN 0-8109-4330-1. OCLC 55019211.

- Okazaki Takashi (岡崎敬), Anagaku sangōhun (Tō Ju bo) no kenkyū (安岳三号墳 (冬寿墓) の研究), Shien (史淵), No.93, pp. 37–84, 1964.

- Takeda Yukio (武田幸男), Kyūryōiki no shihai keitai (旧領域の支配形態), Kōkuri shi to Higashi Ajia (高句麗史と東アジア), pp. 78–107, 1989.

External links

[edit] Media related to Anak Tomb No.3 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Anak Tomb No.3 at Wikimedia Commons