Sneakers (1992 film)

| Sneakers | |

|---|---|

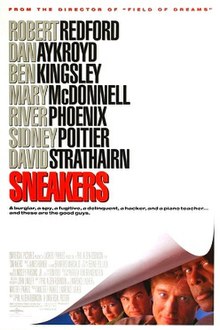

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Phil Alden Robinson |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Lindley |

| Edited by | Tom Rolf |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 126 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $23 million[1] |

| Box office | $105.2 million[2] |

Sneakers is a 1992 American caper thriller film directed by Phil Alden Robinson from a screenplay co-written with Walter Parkes and Lawrence Lasker. It stars Robert Redford, Dan Aykroyd, Ben Kingsley, Mary McDonnell, River Phoenix, Sidney Poitier, and David Strathairn. In the film, Martin (Redford) and his group of security specialists are hired to steal a black box but soon realize the job has nefarious and far-reaching consequences.

Lasker and Parkes first conceived Sneakers in 1981 during pre-production on WarGames (1983). Redford was the first actor attached to the project, and he helped recruit the remaining cast members, as well as Robinson. Several of the characters were inspired by members of the hacking and national defense communities, and the actors improvised several scenes during filming. Principal photography took place on location across California, with filming taking place in San Francisco, Oakland, Simi Valley, and the Courthouse Square backlot at Universal Studios, Hollywood.

Sneakers was theatrically released in the United States on September 11, 1992, by Universal Pictures. The film received generally positive reviews from critics, with praise for its humor, tone, and plot. It grossed $105.2 million worldwide, becoming the 20th highest-grossing film of 1992.[3][2]

Plot

[edit]In 1969, student hackers and long-time friends Martin Brice and Cosmo use their skills to reallocate money from causes they consider evil to noble but underfunded causes designed to help the world. Martin leaves for food just before the police arrive, arresting Cosmo and forcing Martin into hiding.

Decades later, in San Francisco, Martin, using the alias Martin Bishop, heads a penetration testing security specialist team that includes former CIA operative Donald Crease, technician and conspiracy theorist Darren "Mother" Roskow, hacking prodigy Carl Arbogast, and blind phone phreak Irwin "Whistler" Emery. After the team successfully infiltrates a bank to demonstrate their inadequate security, Martin is approached by two NSA agents. The men are aware of Martin's true identity and offer to clear his name and pay him $175,000 to recover a Russian-funded black box device codenamed "Setec Astronomy" from mathematician Gunter Janek. With assistance from his ex-girlfriend Liz, Martin and his team secure the box. However, they discover the device is a code breaker capable of infiltrating the most secure computer networks including financial and government systems. Martin realizes "Setec Astronomy" is an anagram of "too many secrets" and locks everyone down in their office until the device can be delivered to the NSA.

The following day, Martin hands the box to the agents, but Crease warns him to run after learning that Janek was murdered the night before. The team learns the box was actually funded by the NSA and the agents are imposters. Martin's friend Gregor, a spy in the Russian consulate, identifies one of them as a former NSA agent now working for a powerful crime organization. Men impersonating FBI agents arrive and kill Gregor, framing Martin by using his gun, before recovering Martin to an unknown location where it is revealed they are working for Cosmo. Because of his hacking talents, Cosmo had secured an early release from prison and was recruited by a crime organization to manage their illicit finances. Although the box could infiltrate their illegal networks, Cosmo wants it so he can finish what he and Martin started in 1969, destroying financial and ownership records to render the rich and poor as equals. He asks Martin to join him, but he refuses, considering Cosmo's plan extreme. Cosmo uses the box to access the FBI's systems and link Martin's current and former identities, making him a fugitive again. Martin is knocked unconscious and returned to the city.

To conceal their presence, Martin relocates his team to Liz's apartment. They contact NSA director of operations Bernard Abbott who will assist them if they recover the box. Whistler uses the sounds Martin can recall from his abduction to identify Cosmo's office in the PlayTronics toy company. Researching the building's security, the team identifies Werner Brandes, an employee, and manipulate a dating service to connect him with Liz. During the date she steals his access codes which allows Martin to infiltrate PlayTronics, but Brandes becomes suspicious of Liz and takes her to his office. Cosmo realizes she is involved with Martin and locks down the facility, taking Liz hostage. Martin surrenders and Cosmo pleads with Martin to join him, but he refuses after turning over the box. Unable to kill his friend, Cosmo allows Martin and his team to leave, but discovers Martin gave him an empty box.

On arriving back at their office, Martin's team is surrounded by Abbott and his agents. Martin realizes that the box can only be used by the NSA to hack into systems belonging to the USA, such as the FBI and White House. To ensure their silence on the matter, Abbott acquiesces to the team's demands, including clearing Martin's record, sending Crease on a long holiday with his wife, buying Mother a Winnebago, and giving Carl the telephone number of an attractive NSA agent. After the agents leave, Martin reveals the box is useless because he has removed the core component.

A news report announces the sudden bankruptcy of the Republican National Committee and the simultaneous receipt of large anonymous donations to Amnesty International, Greenpeace, and the United Negro College Fund.

Cast

[edit]- Robert Redford as Martin Bishop / Martin Brice

- Gary Hershberger as younger Bishop

- Ben Kingsley as Cosmo

- Jo Marr as younger Cosmo

- Sidney Poitier as Donald Crease

- David Strathairn as Irwin "Whistler" Emery

- Dan Aykroyd as Darren "Mother" Roskow

- River Phoenix as Carl Arbogast

- Mary McDonnell as Liz Ogilvy

- Stephen Tobolowsky as Werner Brandes

- Timothy Busfield as Dick Gordon

- Eddie Jones as Buddy Wallace

- George Hearn as Gregor Ivanovich

- Donal Logue as Dr. Gunter Janek

- Lee Garlington as Dr. Elena Rhyzkov

- James Earl Jones as NSA Agent Bernard Abbott

Production

[edit]Lawrence Lasker and Walter F. Parkes first conceived the idea for Sneakers in 1981, while doing research for WarGames.[4] In early drafts, the character of Liz was a bank employee, rather than Martin's ex-girlfriend. The role was changed because Lasker and Parkes believed that it took too long for her character to develop.[4]

Once Robert Redford was attached to the picture, his name was used to recruit other members of the cast and crew, including the director Robinson, who had little initial interest in the project but had always wanted to work with Redford.[4]

At one point during the project, Robinson received a visit from men claiming to be representatives of the Office of Naval Intelligence, who indicated that for reasons of national security, the film could not include any references to "a hand-held device that can decode codes". Robinson was highly concerned, as such a device was a key to the film's plot, but after consulting with a lawyer from the film studio he realized that the "visit" had been a prank instigated by a member of the cast, possibly Aykroyd or Redford.[4]

Leonard Adleman was the mathematical consultant on this movie.[5] The character of "Bernard Abbott" was named after Robert Abbott, the so-called "Father of Information Security," who was also a consultant for the film. The character "Whistler" was based on Josef "Joybubbles" Engressia and John "Cap'n Crunch" Draper, well-known figures in the phone phreaks and hacking communities.[6] "Donald Crease" was based on John Strauchs, a former CIA officer who founded the security consulting firm Systech Group.[7]

Filming

[edit]Filming took place mainly on-location in San Francisco, Oakland, and other parts of the Bay Area.[7] The opening scene was shot at the "Courthouse Square" set on the Universal Studios Hollywood backlot, better known as "Hill Valley" in the Back to the Future films.[7] The "Playtronics" building was a former headquarters for Gibraltar Savings and Loan in Simi Valley, California.[7]

"I can't remember having so much fun on a movie," Stephen Tobolowsky recalled in 2012 for a 20th-anniversary piece about the film for Slate. He had initially scoffed at the script based on its title alone, but his agent persuaded him to read it, and he reconsidered. Afterward, he told his agent, "Now I know what a hundred million dollars at the box office reads like."[8] "It was one of the most spectacular casts I've ever been lucky enough to be a part of," Tobolowsky wrote. When he was shooting the scene where he and McDonnell eat at a Chinese restaurant, Robinson told him he could do anything he wanted to make her laugh. "Dangerous words. It set the tone for the rest of the shoot," he recalls. "I played with my food. I made up lines (including one about pounding chicken breasts in the kitchen during our second date)." The rest of the cast and crew felt similarly. Near the end of the shoot, Robinson said the only way it could have been better would have been if the lab lost the film, so they would have had to do it all over again.[8]

Release

[edit]The film's press kit was accompanied by a floppy disk containing a custom program explaining the movie. Parts of the program were quasi-encrypted, requiring the user to enter an easily guessable password to proceed.[9] It was one of the first electronic press kits by a film studio.[10]

Reception

[edit]The film received positive reviews from critics upon its release. Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Kenneth Turan called Sneakers "[a] caper movie with a most pleasant sense of humor," a "twisting plot," and a "witty, hang-loose tone." Turan went on to praise the ensemble cast and director Robinson, who is "surprisingly adept at creating tension at appropriate moments" and "makes good use of the script's air of clever cheerfulness".[11] Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, was less impressed, giving the film two-and-a-half stars out of four, calling it "a sometimes entertaining movie, but thin." He went on to point out numerous clichés and tired plot devices recycled in the film.[12]

Conversely, Vincent Canby, in a negative review for The New York Times, said the film looked like it had "just surfaced after being buried alive for 20 years," calling it "an atrophied version of a kind of caper movie that was so beloved in the early 1970's". He singled out Redford and Poitier as looking and acting too old to be in this kind of film now. He calls the plot "feeble," resulting in a film that is "jokey without being funny, breathless without creating suspense". He calls the ensemble an "all-star gang," but says the "performances are generally quite bad."[13]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 80% based on reviews from 55 critics. The website's consensus states: "There isn't much to Sneakers' plot and that's more than made up for with the film's breezy panache and hi-tech lingo."[3] On Metacritic the film has a score of 65 out of 100 based on reviews from 20 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[14] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade A− on scale of A to F.[15]

The film was a box office success, grossing over $105.2 million worldwide.[2]

Novelization

[edit]A novelization of the film written by Dewey Gram was published in English (Signet, 1992, ISBN 0451174704) and translated into German (Droemer Knaur, 1993, ISBN 3-426-60177-X).

Potential TV series

[edit]In October 2016, NBC was developing a TV series based on the film. Writer Walter Parkes was brought on as an executive producer.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com.

- ^ a b c "Sneakers Races to the Top Spot". Los Angeles Times. 1992-09-15. Archived from the original on 2013-11-06. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ a b "Sneakers (1992)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ^ a b c d Weidman, Sara (October 8, 1992). "A Decade Later, 'Sneakers' is Complete". The Michigan Daily. p. 8.

- ^ "Sneakers". www.usc.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-01. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ McCracken, Elizabeth (2007-12-30). "Dial-Tone Phreak". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ a b c d "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ a b Tobolowsky, Stephen (September 10, 2012). "Memories of the Sneakers Shoot". Slate. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "Sneakers Computer Press Kit". Internet Archive. July 12, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ O'Steen, Kathleen (November 15, 1994). "WB goes interactive for 'Disclosure' push". Daily Variety. p. 5.

- ^ "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Sneakers': A Caper With Lots of Twists". Los Angeles Times. 1992-09-09. Archived from the original on 2013-04-24. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ Roger Ebert (September 9, 1992). "Sneakers". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "Reviews/Film; A 1970's Caper Movie With Heroes of the Time". The New York Times. 1992-09-09. Archived from the original on 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ "Sneakers". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ "SNEAKERS (1992) A-". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018.

- ^ "'Sneaker' Hacker Drama Based On Movie in Works at NBC From Walter Parkes, Laurie Macdonald & Tom Szentgyorgyi". Deadline Hollywood. 2016-10-23. Archived from the original on 2016-10-23. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

External links

[edit]- 1992 films

- 1990s heist films

- 1990s crime comedy films

- 1992 comedy films

- American comedy thriller films

- American crime comedy films

- American heist films

- Fiction about cryptography

- Films about computer hacking

- Films about computing

- Films about mathematics

- Films about security and surveillance

- Films about the National Security Agency

- Films directed by Phil Alden Robinson

- Films produced by Walter F. Parkes

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films set in 1969

- Films set in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Films with screenplays by Walter F. Parkes

- Universal Pictures films

- Works about computer hacking

- Techno-thriller films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- English-language crime comedy films