Saint George and the Dragon

In a legend, Saint George—a soldier venerated in Christianity—defeats a dragon. The story goes that the dragon originally extorted tribute from villagers. When they ran out of livestock and trinkets for the dragon, they started giving up a human tribute once a day. And, one day, the princess herself was chosen as the next offering. As she was walking towards the dragon's cave, St. George saw her and asked her why she was crying. The princess told the saint about the dragon's atrocities and asked him to flee immediately, in fear that he might be killed too. But the saint refused to flee, slayed the dragon, and rescued the princess. The narrative was first set in Cappadocia in the earliest sources of the 11th and 12th centuries, but transferred to Libya in the 13th-century Golden Legend.[1]

The narrative has pre-Christian origins (Jason and Medea, Perseus and Andromeda, Typhon, etc.),[1] and is recorded in various saints' lives prior to its attribution to Saint George specifically. It was particularly attributed to Saint Theodore Tiro in the 9th and 10th centuries, and was first transferred to Saint George in the 11th century. The oldest known record of Saint George slaying a dragon is found in a Georgian text of the 11th century.[2][3]

The legend and iconography spread rapidly through the Byzantine cultural sphere in the 12th century. It reached Western Christian tradition still in the 12th century, via the crusades. The knights of the First Crusade believed that Saint George, along with his fellow soldier-saints Demetrius, Maurice, Theodore and Mercurius, had fought alongside them at Antioch and Jerusalem. The legend was popularised in Western tradition in the 13th century based on its Latin versions in the Speculum Historiale and the Golden Legend. At first limited to the courtly setting of chivalric romance, the legend was popularised in the 13th century and became a favourite literary and pictorial subject in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, and it has become an integral part of the Christian traditions relating to Saint George in both Eastern and Western tradition.

Origins

[edit]Pre-Christian predecessors

[edit]The iconography of military saints Theodore, George and Demetrius as horsemen is a direct continuation of the Roman-era "Thracian horseman" type iconography. The iconography of the dragon appears to grow out of the serpent entwining the "tree of life" on one hand, and with the draco standard used by late Roman cavalry on the other. Horsemen spearing serpents and boars are widely represented in Roman-era stelae commemorating cavalry soldiers. A carving from Krupac, Serbia, depicts Apollo and Asclepius as Thracian horsemen, shown besides the serpent entwined around the tree. Another stele shows the Dioscuri as Thracian horsemen on either side of the serpent-entwined tree, killing a boar with their spears.[4]

The development of the hagiographical narrative of the dragon-fight parallels the development of iconography. It draws from pre-Christian dragon myths. The Coptic version of the Saint George legend, edited by E. A. Wallis Budge in 1888, and estimated by Budge to be based on a source of the 5th or 6th century, names "governor Dadianus", the persecutor of Saint George as "the dragon of the abyss", a greek myth with similar elements of the legend is the battle between Bellerophon and the Chimera. Budge makes explicit the parallel to pre-Christian myth:

I doubt much of the whole story of Saint George is anything more than one of the many versions of the old-world story of the conflict between Light and Darkness, or Ra and Apepi, and Marduk and Tiamat, woven upon a few slender threads of historical fact. Tiamat, the scaly, winged, foul dragon, and Apepi the powerful enemy of the glorious Sungod, were both destroyed and made to perish in the fire which he sent against them and their fiends: and Dadianus, also called the 'dragon', with his friends the sixty-nine governors, was also destroyed by fire called down from heaven by the prayer of Saint George.[5]

In anticipation of the Saint George iconography, first noted in the 1870s, a Coptic stone fenestrella shows a mounted hawk-headed figure fighting a crocodile, interpreted by the Louvre as Horus killing a metamorphosed Setekh.[6]

-

Thracian horseman with serpent-entwined tree (2nd century)

-

Funerary relief of a Roman cavalryman trampling a barbarian warrior (4th or 5th century).

Grosvenor Museum, Chester

Christianised iconography

[edit]Depictions of "Christ militant" trampling a serpent is found in Christian art of the late 5th century. Iconography of the horseman with spear overcoming evil becomes current in the early medieval period. Iconographic representations of St Theodore as dragon-slayer are dated to as early as the 7th century, certainly by the early 10th century (the oldest certain depiction of Theodore killing a dragon is at Aghtamar, dated c. 920).[7] Theodore is reported as having destroyed a dragon near Euchaita in a legend not younger than the late 9th century. Early depictions of a horseman killing a dragon are unlikely to represent Saint George, who in the 10th century was depicted as killing a human figure, not a dragon.[8]

The earliest image of St Theodore as a horseman (named in Latin) is from Vinica, North Macedonia and, if genuine, dates to the 6th or 7th century. Here, Theodore is not slaying a dragon, but holding a draco standard. One of the Vinica icons also has the oldest representation of Saint George with a dragon: George stands besides a cynocephalous Saint Christopher, both saints treading on snakes with human heads, and aiming at their heads with spears.[9] Maguire (1996) has connected the shift from unnamed equestrian heroes used in household magic to the more regulated iconography of named saints to the closer regulation of sacred imagery following the iconoclasm of the 730s.[4]

In the West, a Carolingian-era depiction of a Roman horseman trampling and piercing a dragon between two soldier saints with lances and shields was put on the foot of a crux gemmata, formerly in the Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius in Maastricht (lost since the 18th c.). The representation survives in a 17th-century drawing, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

The "Christianisation" of the Thracian horseman iconography can be traced to the Cappadocian cave churches of Göreme, where frescoes of the 10th century show military saints on horseback confronting serpents with one, two or three heads. One of the earliest examples is from the church known as Mavrucan 3 (Güzelöz, Yeşilhisar), generally dated to the 10th century,[10] which portrays two "sacred riders" confronting two serpents twined around a tree, in a striking parallel to the Dioskuroi stela, except that the riders are now attacking the snake in the "tree of life" instead of a boar. In this example, at least, there appear to be two snakes with separate heads, but other examples of 10th-century Cappadocia show polycephalous snakes.[4] A poorly preserved wall-painting at the Yılanlı Kilise ("Snake Church") that depicts the two saints Theodore and George attacking a dragon has been tentatively dated to the 10th century,[11] or alternatively even to the mid-9th.[12][need quotation to verify]

A similar example, but showing three equestrian saints, Demetrius, Theodore and George, is from the "Zoodochos Pigi" chapel in central Macedonia in Greece, in the prefecture of Kilkis, near the modern village of Kolchida, dated to the 9th or 10th century.[13]

A 12th-century depiction of the mounted dragon-slayer, presumably depicting Theodore, not George, is found in four muqarna panels in the nave of the Cappella Palatina in Palermo.[7]

Transfer to Saint George

[edit]

The dragon motif was transferred to the George legend from that of his fellow soldier saint, Saint Theodore Tiro.[14]

The transfer of the dragon iconography from Theodore, or Theodore and George as "Dioskuroi" to George on his own, first becomes tangible in the early 11th century. [15] The oldest certain images of Saint George combatting the serpent are still found in Cappadocia.

Golden Legend

[edit]In the well-known version from Jacobus de Voragine's Legenda aurea (The Golden Legend, 1260s), the narrative episode of Saint George and the Dragon took place somewhere he called "Silene" in what in medieval times was referred to as "Libya" (basically anywhere in North Africa, west of the Nile).[16][17] Silene was being plagued by a venom-spewing dragon dwelling in a nearby pond, poisoning the countryside. To prevent it from affecting the city itself, the people offered it two sheep daily, then a man and a sheep, and finally their children and youths, chosen by lottery. One time the lot fell on the king's daughter. The king offered all his gold and silver to have his daughter spared, but the people refused. The daughter was sent out to the lake, dressed as a bride, to be fed to the dragon.

Saint George arrived at the spot. The princess tried to send him away, but he vowed to remain. The dragon emerged from the pond while they were conversing. Saint George made the Sign of the Cross and charged it on horseback, seriously wounding it with his lance.[a] He then called to the princess to throw him her girdle (zona), and he put it around the dragon's neck. Wherever she walked, the dragon followed the girl like a "meek beast" on a leash.[b]

The princess and Saint George led the dragon back to the city of Silene, where it terrified the population. Saint George offered to kill the dragon if they consented to become Christians and be baptized. Fifteen thousand men including the king of Silene converted to Christianity.[c] George then killed the dragon, beheading it with his sword, and the body was carted out of the city on four ox-carts. The king built a church to the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint George on the site where the dragon died and a spring flowed from its altar with water that cured all disease.[18] Only the Latin version involves the saint striking the dragon with the spear, before killing it with the sword.[19]

The Golden Legend narrative is the main source of the story of Saint George and the Dragon as received in Western Europe, and is therefore relevant for Saint George as patron saint of England. The princess remains unnamed in the Golden Legend version, and the name "Sabra" is supplied by Elizabethan era writer Richard Johnson in his Seven Champions of Christendom (1596). In the work, she is recast as a princess of Egypt.[20][21] This work takes great liberties with the material, and makes Saint George marry Sabra[d] and have English children, one of whom becomes Guy of Warwick.[22] Alternative names given to the princess in Italian sources still of the 13th century are Cleolinda and Aia.[23] Johnson also supplied the name of Saint George's sword: "Ascalon".[24] The story of Saint George, as the Red Cross Knight and the patron saint of England, slaying the dragon, which represents sin, and Princess Una as George's true love and an allegory representing the Protestant church as the one true faith, was told in altered fashion in Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene.[25] [26]

-

Princess Sabra (the King's Daughter), by Edward Burne-Jones, 1865.

-

Princess Sabra Led to the Dragon by Edward Burne-Jones, 1866

-

The Princess Sabra Taken to the Dragon, by Henry Treffry Dunn, 1896.

-

The Princess Tied to the Tree by Edward Burne-Jones, 1866.

-

The Fight: Saint George Kills the Dragon, by Edward Burne-Jones, 1866.

-

Saint George Slaying The Dragon, With Una Praying In The Background, by Phoebe Anna Traquair, 1904.

-

Una and the Lion by William Bell Scott, 1860.

-

Una and the Red Cross Knight by George Frederic Watts, 1860.

-

Saint George and Princess Sabra by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1862.

-

The Wedding of Saint George and Princess Sabra by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1857.

Iconography

[edit]Medieval iconography

[edit]

Eastern

[edit]The saint is depicted in the style of a Roman cavalryman in the tradition of the "Thracian Heros". There are two main iconographic types, the "concise" form showing only George and the dragon, and the "detailed" form also including the princess and the city walls or towers of Lacia (Lasia) with spectators witnessing the miracle. The "concise" type originates in Cappadocia, in the 10th to 11th century (transferred from the same iconography associated with Saint Theodore of Tiro in the 9th to 10th century). The earliest certain example of the "detailed" form may be a fresco from Pavnisi (dated c. 1160), although the examples from Adishi, Bochorma and Ikvi may be slightly earlier.[28]

- Georgian

-

Saint George of Parakheti, Georgia, late 10th century

-

Saint George of Labechina, Racha, Georgia, early 11th century

-

Icon of Saint George and the dragon from Likhauri (Ozurgeti Municipality), Georgia, 12th century

-

A 15th-century Georgian cloisonné enamel icon

- Greek

-

Byzantine bas-relief of Saint George and the Dragon (steatite), 12th century

-

Monumental vita icon at Sinai, first half of the 13th century, likely by a Greek artist. The dragon episode is shown in one of twenty panels depicting the saint's life.

-

Icon by Angelos Akotandos, Crete (first half of the 15th century)

-

"Pedestrian" St George, Crete, second half of the 15th century

-

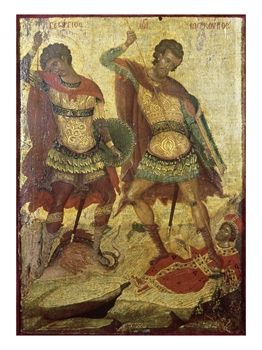

Michael Damaskinos (16th century), Saint George killing the dragon, alongside Saint Mercurius killing Julian.

- Russian

The oldest example in Russia found on walls of the church of St George in Staraya Ladoga, dated c. 1167. In Russian tradition, the icon is known as Чудо Георгия о змие; i.e., "the miracle of George and the dragon". The saint is mostly shown on a white horse, facing right, but sometimes also on a black horse, or facing left.[29] [30] The princess is usually not included. Another motif shows George on horseback with the youth of Mytilene sitting behind him.

-

The Staraya Ladoga fresco, c. 1167

-

14th-century icon from Novgorod

-

14th-century icon from Rostov

-

Novgorod vita icon, 14th century; the "detailed" dragon iconography takes the central panel.

-

Russian icon of the "detailed" type, Moscow, early 15th century

-

Novgorod icon, late 15th century

-

Northern Russian icon of the "detailed" type, the saint is exceptionally slaying the dragon with his sword (c. 1500).

-

Chełm school, 16th century

- Ethiopian

-

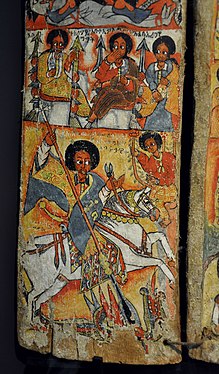

Great Triptych, Ethiopia, c. 1700, tempera on fabric on wood; Museum Rietberg, Zurich, Switzerland

-

Alwan Codex 27 Ethiopian Biblical Icon - Saint George (20th century)

Western

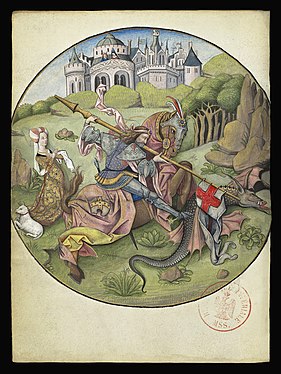

[edit]The motif of Saint George as a knight on horseback slaying the dragon first appears in western art in the second half of the 13th century. The tradition of the saint's arms being shown as the red-on-white Saint George's Cross develops in the 14th century.

-

13th-century fresco in Ankershagen, Mecklenburg

-

Miniature from a Passio Sancti Georgii manuscript (Verona, second half of 13th century)

-

Miniature from a manuscript of Legenda Aurea, Paris, 1348.

-

Book of Hours (c. 1380?).

-

Miniature from a manuscript of Legenda Aurea, Paris, 1382.

-

De Grey Hours (c. 1400)

-

Fresco of the full legend, Anga Church, Gotland, Sweden (mid 15th century)

-

Miniature from Heures de Charles d'Angoulême, Cognac, France, f.53v (1475–1500)

-

Saint George and the Dragon, tinted alabaster, English, c. 1375–1420 (National Gallery of Art, Washington)

-

Wooden sculpture, c. 1500, Gottorf Castle

Renaissance

[edit]- Donatello, Saint George, c. 1417. Bargello, Florence, Italy.

- Paolo Uccello, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1470. National Gallery, London.

- Giovanni Bellini, Saint George Fighting the Dragon, c. 1471. Pesaro altarpiece.[31]

- Lieven van Lathem, Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1471)

- Bernt Notke, Saint George and the Dragon, Storkyrkan in Stockholm, c. 1484–1489.[32]

- Andrea della Robbia, terracotta, c. 1490

- Albrecht Dürer, woodcut, 1501/4

- Raphael (Raffaello Santi), Saint George, 1504. Oil on wood. Louvre, Paris, France.

- Raphael (Raffaello Santi), Saint George and the Dragon, 1504–1506. Oil on wood. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States.

- Albrecht Altdorfer, Forest Landscape with Saint George Fighting the Dragon, 1510

- Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), Saint George and the Dragon, 1555.[33]

-

]] (1435).

-

Saint George on Horseback, Master of the Döbeln Altarpiece, 1511/13, Hamburger Kunsthalle

-

Woodcut frontispiece of Alexander Barclay, Lyfe of Seynt George (Westminster, 1515).

-

Gillis Coignet – Saint George the Great (1581).

Early modern and modern art

[edit]Paintings

- Peter Paul Rubens, Saint George and the Dragon, 1620.

- Salvator Rosa, Saint George and the Dragon

- Mattia Preti, Saint George Triumphant over the Dragon, 1678, at St. George's Basilica, Malta in Victoria, Gozo.

- Edward Burne-Jones, Saint George and the Dragon, 1866.[34]

- Gustave Moreau, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1870. Oil on canvas. The National Gallery, London.

- Briton Rivière, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1914.

- Uroš Predić, St George Killing the Dragon, 1930.

- Giorgio de Chirico, Saint George Killing the Dragon, 1940.[35]

Sculptures

- The sculptures which form part of the clock of Liberty's store in Regent Street, London (19th century).[36]

- Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm, Saint George and the Dragon, bronze, State Library of Victoria, 1889[37]

- Salvador Dalí, Saint George and the Dragon, Open Air Museum in Cosenza, 1947

- Edward Seago, Saint George and the Dragon, silver, automobile mascot used for the British monarch's cars, 1952.[38]

- Zurab Tsereteli, sculpture in front of the Victory Monument at Victory Park, Moscow, 1995

- Zurab Tsereteli, Saint George Statue, Tbilisi, 2005

- Marcus Canning and Christian de Vietri, Ascalon, abstract sculpture in front of St George's Cathedral, Perth, 2011[39]

Mosaic

- Edward Poynter, Saint George for England, 1869. Central Lobby in the Palace of Westminster.

- Sergey Chekhonin, Sergey Vasilyevich Gerasimov, Central maiolica panel about the battle of Saint George the Victorious with the Serpent 1911–1913, Moscow, Russia.

- Anatoly Alexandrovich Ostrogradsky, A small image of Saint George, with the plot of the fresco of the Church of St. George in Staraya Ladoga in a stylized icon case on the façade, above the main porches, the maiolica was made in 1911–1913, Moscow, Russia.

Engravings

- Benedetto Pistrucci, engraving for coin dies, 1817.

- On kopecks issued by the Central Bank of Russia.

Prints

- On banknotes issued by the Bank of England:

-

17th-century statue in Église Saint-Georges de Châtenois, France

-

18th-century statue in Église Saint-Georges de Châtenois, France

-

Unknown painter from Ukraine, 18th century.

-

Pendant with Saint George by Lluís Masriera i Rosés (1902), Barcelona.

-

St. George and the Dragon by Briton Reviere (c. 1914).

-

1914 sovereign with Benedetto Pistrucci's engraving.

-

WWI British recruitment poster.

-

Edward Seago's St. George and the Dragon automobile mascot used by the British monarch (1952)

-

Central maiolica panel about the battle of St. George the Victorious with the Serpent 1911–1913, artists Sergey Chekhonin, Sergey Vasilyevich Gerasimov

-

A small image of St. George, with the plot of the fresco of the Church of St. George in Staraya Ladoga in a stylized icon case on the facade, above the main porches, the maiolica was made in 1911–1913 by Anatoly Alexandrovich Ostrogradsky.

-

Zurab Tsereteli's St. George and the Dragon on the top of the Okhotny Ryad shopping center (1997) in Moscow, Russia

Literary adaptations

[edit]Edmund Spenser expands on the Saint George and the Dragon story in Book I of the Fairy Queen, initially referring to the hero as the Redcross Knight. William Shakespeare refers to Saint George and the Dragon in Richard III ( Advance our standards, set upon our foes Our ancient world of courage fair St. George Inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons act V, sc. 3), Henry V ( The game's afoot: follow your spirit, and upon this charge cry 'God for Harry, England, and Saint George!' act III, sc. 1), and also in King Lear (act I).

A 17th-century broadside ballad paid homage to the feat of George's dragon slaying. Titled "St. George and the Dragon", the ballad considers the importance of Saint George in relation to other heroes of epic and Romance, ultimately concluding that all other heroes and figures of epic or romance pale in comparison to the feats of George.[41]

The Banner of St George by Edward Elgar is a ballad for chorus and orchestra, words by Shapcott Wensley (1879). The 1898 Dream Days by Kenneth Grahame includes a chapter entitled "The Reluctant Dragon", in which an elderly Saint George and a benign dragon stage a mock battle to satisfy the townsfolk and get the dragon introduced into society. Later made into a film by Walt Disney Productions, and set to music by John Rutter as a children's operetta.

In 1935 Stanley Holloway recorded a humorous retelling of the tale as St. George and the Dragon written by Weston and Lee. In the 1950s, Stan Freberg and Daws Butler wrote and performed St. George and the Dragon-Net (a spoof of the tale and of Dragnet) for Freberg's radio show. The story's recording became the first comedy album to sell over a million copies.

Margaret Hodges retold the legend in a 1984 children's book (Saint George and the Dragon) with Caldecott Medal-winning illustrations by Trina Schart Hyman.

The Forever Knights that serve as a recurring antagonist faction in the Ben 10 are revealed in the third series Ben 10: Ultimate Alien to have been founded by Sir George from the legend of Saint George and the Dragon, with the tale directly referenced by name. The dragon that George fought is depicted as a shapeshifting extradimensional demon named Dagon, worshipped by a cult called the Flame Keepers’ Circle that goes to war against the Forever Knights. Series main antagonist Vilgax takes advantage of his true form’s coincidental resemblance to Dagon’s true appearance to manipulate the Flame Keepers’ Circle into helping him find the heart of Dagon, which George had cut out and sealed with the Ascalon, depicted here as a sword of alien origin created by Azmuth prior to inventing the Omnitrix.

Samantha Shannon describes her 2019 novel The Priory of the Orange Tree as a "feminist retelling" of Saint George and the Dragon.[42]

Heraldry and vexillology

[edit]Coats of arms

[edit]Reggio Calabria used Saint George and the dragon in its coat of arms since at least 1757, derived from earlier (15th-century) iconography used on the city seal. Saint George and the dragon has been depicted in the coat of arms of Moscow since the late 18th century, and in the coat of arms of Georgia since 1991 (based on a coat of arms introduced in 1801 for Georgia within the Russian Empire).

-

Coat of arms of Reggio Calabria (1896)

-

Coat of arms of Moscow (1781)

-

Coat of arms of Moscow (1993 design)

-

Coat of arms of Russia (1993)

-

Coat of arms of Kyiv Oblast (1999)

-

Coat of arms of Georgia (2004)

- Provincial coats of arms

- Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine (1999)

- Moscow Oblast, Russia (2005)

- Municipal coats of arms

- Australia: Hurstville

- Austria: Pitten, Sankt Georgen an der Gusen, Sankt Georgen an der Leys, Sankt Georgen an der Stiefing, Sankt Georgen im Attergau, Sankt Georgen ob Murau.

- Croatia: Kaštel Sućurac, Vis.

- Czech Republic: Brušperk.

- Denmark: Holstebro.

- France: Aydoilles, Couilly-Pont-aux-Dames, Ligsdorf, Maulan, Mussidan, Saint-Georges (Moselle), Saint-Georges-Armont, Saint-Georges-d'Espéranche, Saint-Georges-d'Oléron, Saint-Georges-d'Orques, Saint-Georges-de-Reintembault, Saint-Georges-du-Bois, Saint-Georges-du-Vièvre, Saint-Georges-sur-Baulche, Saint-Georges-sur-Loire, Saint-Jurs, Saorge, Sospel, Villeneuve-Saint-Georges.

- Germany: Bürgel, Hattingen, Mansfeld, Rittersbach, St. Georgen im Schwarzwald, Schwarzenberg.

- Hungary: Bácsszentgyörgy, Balatonszentgyörgy, Borsodszentgyörgy, Dunaszentgyörgy, Homokszentgyörgy, Pécsvárad, Szentgyörgyvár, Szentgyörgyvölgy, Tatárszentgyörgy.

- Italy: Reggio Calabria

- Lithuania: Marijampolė, Prienai, Varniai.

- Netherlands: Ridderkerk, Terborg.

- Poland: Brzeg Dolny, Dzierżoniów, Milicz, Ostróda.

- Romania: Suceava, Sfântu Gheorghe.

- Russia: Moscow

- Serbia: Srpski Krstur.

- Slovakia: Svätý Jur.

- Slovenia: Šenčur, Šentjur

- Spain: Alcalá de los Gazules, Golosalvo, Puentedura.

- Switzerland: Castiel, Kaltbrunn, Ruschein, Saint-George, Schlans, Stein am Rhein, Waltensburg/Vuorz.

- Ukraine: Holoby, Liuboml, Nizhyn, Taikury, Volodymyr, Vyshneve, Zbarazh.

Flags

[edit]-

Standard of Greek general Markos Botsaris

-

Imperial standard of Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia (reverse)

Military insignia

[edit]- Regimental flags of the Hellenic Army (1864)

- Badge of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers (1968)

- Flag of the Russian Orthodox Army (2014)

See also

[edit]- Bakasura

- Saint George

- Saint George in devotions, traditions and prayers

- Princess and dragon

- Ducasse de Mons

- Dragon Hill, Uffington

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Caxton gives "with his spear", but Latin text gives lanceam fortiter vibrans.

- ^ Caxton gives "meek beast", but Latin text gives "mansuetissima canis (tamest dog)".

- ^ Latin text gives XX thousand.

- ^ Saint George is supposed to have been martyred as a virgin according to his hagiography.

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ a b St. George and the Dragon: Introduction in: E. Gordon Whatley, Anne B. Thompson, Robert K. Upchurch, eds. (2004). Saints' Lives in Middle Spanish Collections.

- ^ Privalova, E. L. (1977). Pavnisi (in Russian). Tbilisi: Metsniereba. p. 73.

- ^ Tuite, Kevin (2022). "The Old Georgian Version of the Miracle of St George, the Princess and the Dragon: Text, Commentary and Translation". In Dorfmann-Lazarev, Igor (ed.). Sharing Myths, Texts and Sanctuaries in the South Caucasus: Apocryphal Themes in Literatures, Arts and Cults from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages (PDF). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 60–94. ISBN 9789042947146.

- ^ a b c Paul Stephenson, The Serpent Column: A Cultural Biography, Oxford University Press (2016), 179–182.

- ^ E. A. Wallis Budge, The Martyrdom and Miracles of Saint George of Cappadocia (1888), xxxi–xxxiii; 206, 223. Budge (1930), 33–44 also likens George against Dadianus to Horos against Set or Ra against Apep. See also Joseph Eddy Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins (1959), p. 518 (fn 8).

- ^ Charles Clermont-Ganneau, "Horus et Saint Georges, d'après un bas-relief inédit du Louvre". Revue archéologique, 1876. "Horus on horseback | Louvre Museum | Paris". louvre.fr..

- ^ a b Johns (2017) p. 170f. Jeremy Johns, "Muslim Artists, Christian Patrons and the Painted Ceilings of the Cappella Palatina (Palermo, Sicily, circa 1143 CE)", Hadiith ad-Dar 40 Archived 2020-07-27 at the Wayback Machine (2016), p. 15.

- ^ Walter (1995), p. 320.

- ^ Jan Bazant, "St. George at Prague Castle and Perseus: an Impossible Encounter?", Studia Hercynia 19.1-2 (2015), 189-201 (fig. 4).

- ^ "Thierry 1972, who dates the fresco to as early as the seventh century. However, this seems unlikely, as it would be three hundred years earlier than any other church fresco in the region." Stephenson (2016), 180 (fn 89). see also: Walter (2003), pp. 56, 125, plate 27.

- ^ Johns (2017) p. 170 "the pairing of the two holy dragon-slayers has no narrative source, and the symbolic meaning of the scene is spelled out in an inscription written on both sides of the central cross, which compares the victory of the two saints over the dragon to Christ's triumph over evil on the cross."

- ^ Walter (2003), p. 128.

- ^ Melina Paissidou, "Warrior Saints as Protectors of the Byzantine Army in the Palaiologan Period: the Case of the Rock-cut Hermitage in Kolchida (Kilkis Prefecture)", in: Ivanka Gergova Emmanuel Moutafov (eds.), ГЕРОИ • КУЛТОВЕ • СВЕТЦИ / Heroes Cults Saints Sofija (2015), 181-198.

- ^ Robertson, Duncan (1998), The Medieval Saints' Lives, pp. 51 f.

- ^ Oya Pancaroğlu, “The Itinerant Dragon-Slayer: Forging Paths of Image and Identity in Medieval Anatolia.” Gesta 43, no. 2 (2004): 153. https://doi.org/10.2307/25067102

- ^ Jacobus (de Voragine) (1890), Graesse, Theodor (ed.), "Cap. LVIII. De sancto Georgio", Legenda aurea: vulgo Historia lombardica dicta, pp. 260–264

- ^ Jacobus (de Voragine) (1900), Caxton, William (tr.) (ed.), "Here followeth the Life of S. George Martyr", The Golden Legend: Or, Lives of the Saints, vol. 3, Dent, p. 126

- ^ Thus Jacobus de Voragine, in William Caxton's translation (On-line text).

- ^ Johns, Jeremy (2017), Bacile, Rosa (ed.), "Muslim Artists and Christian Moels in the Painted Ceilings of the Cappella Palatina", Romanesque and the Mediterranean, Routledge, ISBN 9781351191050, note 96

- ^ Chambers, Edmund Kerchever, ed. (1878), The Mediaeval Stage: book I. Minstrelsy. book II. Folk drama, Halle: M. Niemeyer, p. 221, note 2

- ^ Graf, Arturo, ed. (1878), Auberon (I complementi della Chanson d'Huon de Bordeaux I), Archivio per lo studio delle tradizioni popolari (10) (in Italian), Halle: M. Niemeyer, p. 261

- ^ Richmond, Velma Bourgeois (1996), The Legend of Guy of Warwick, New York: Garland, p. 221, note 2, ISBN 9780815320852

- ^ Runcini, Romolo (1999), Metamorfosi del fantastico: luoghi e figure nella letteratura, nel cinema, massmedia (in Italian), Lithos, p. 184, note 13, ISBN 9788886584364

- ^ Johnson, Richard (1861). The Seven Champions of Christendom. London: J. Blackwood & Co. p. 7.

- ^ Christian, Margaret (2018). ""The dragon is sin": Spenser's Book I as Evangelical Fantasy". Spenser Studies. 31–32: 349–368. doi:10.1086/695582. S2CID 192276004.

- ^ "Una in the Faerie Queen: An Allegory of the One True Church". 16 May 2022.

- ^ Jonathan David Arthur Good, Saint George for England: Sanctity and National Identity, 1272-1509 (2004), p. 102.

- ^ Walter (2003:142).

- ^ notably the icon known as "Black George", showing the saint both on a black horse and facing left, made in Novgorod in the first half of the 15th century (BM 1986,0603.1)

- ^ "a few 14th–16th century Novgorod icons such as the 'Miracle of St George', a mid-14th-century icon from the Morozov collection and now in the Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow (Bruk and Iovleva 1995, no. 21), 'St George, Nikita and the Deesis', a 16th-century icon in the Russian Museum, St Petersburg, (Likhachov, Laurina and Pushkariov 1980, fig. 237) and on some Northern Russian icons, for instance, the 'Miracle of St George and his Life' from Ustjuznan and dating from the first half of the 16th century (Rybakov 1995, fig. 214)" British Museum Russian Icon "The Miracle of St George and the Dragon / Black George".

- ^ [1] Archived February 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nordisk familjebok. 1914.

- ^ [2] Archived September 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burne-Jones, Sir Edward. "St. George and the Dragon". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Giorgio de Chirico. "St. George Killing the Dragon - Giorgio de Chirico. Wikiart.com". Wikiart.org. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ The Liberty Clock waymarking.com.

- ^ "Forecourt Statues of The State Library of Victoria". THE GARGAREAN. WordPress.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "The Royal Fleet of Limousines". The Chauffeur. 6 October 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Ascalon | St George's Cathedral". www.perthcathedral.org. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ "Withdrawn Banknotes: Reference Guide" (PDF). Bank of England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "New Ballad of St. George and the Dragon (EBBA 34079)". English Broadside Ballad Archive. National Library of Scotland - Crawford 1349: University of California at Santa Barbara, Department of English. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Shelfie with Samantha Shannon". YouTube. 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ Domènech i Montaner, Lluís (1995) Ensenyes nacionals de Catalunya. Barcelona : Generalitat de Catalunya. ISBN 84-393-3575-X.

- Sources

- Mina, John Louis (1979). Thematic and Poetic Analysis of Russian Religious Oral Epics: Epic Duxovnye Stixi (Thesis). University of California, Berkeley. p. 73.

- Warner, Elizabeth (2002). Russian Myths. University of Texas Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-2927-9158-9.

- MacDermott, Mercia (1998). Bulgarian Folk Customs. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-1-8530-2485-6.

- Bibliography

- Aufhauser, Johannes B. (1911), Das Drachenwunder des Heiligen Georg: nach der meist verbreiteten griechischen Rezension, Leipzig, B.G. Teubner

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy (1959), "Appendix 4: Saint George and the Dragon", Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins, University of California Press, pp. 515–520, ISBN 9780520040915

- Loomis, C. Grant, 1949. White Magic, An Introduction to the Folklore of Christian Legend (Cambridge: Medieval Society of America)

- Thurston, Herbert (1909), "St. George", The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 6, New York: Robert Appleton Company, pp. 453–455

- Walter, C. (1995), "The Origins of the Cult of St. George", Revue des études byzantines, 53: 295–326, doi:10.3406/rebyz.1995.1911, ISSN 0766-5598.

- Walter, Christopher (2003), The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition, Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 9781351880510.

- Whatley, E. Gordon, editor, with Anne B. Thompson and Robert K. Upchurch, 2004. St. George and the Dragon in the South English Legendary (East Midland Revision, c. 1400) Originally published in Saints' Lives in Middle English Collections (on-line text: Introduction).

External links

[edit]- Saint George Legend explained in Javascript by Tomás Corral

- St George and the Dragon Events and Ideas – Official Website for Tourism in England

- St George Unofficial Bank Holiday: St. George and the Dragon, free illustrated book based on 'The Seven Champions' by Richard Johnson (1596)

- St George's Bake and Brew Archived 2012-12-24 at archive.today

![]] (1435).](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/Bernat_Martorell_-_Saint_George_Killing_the_Dragon_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/236px-Bernat_Martorell_-_Saint_George_Killing_the_Dragon_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

![Zurab Tsereteli's St. George and the Dragon on the top of the Okhotny Ryad [ru] shopping center (1997) in Moscow, Russia](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B5%D0%B6%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%8F_%D0%BF%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%89%D0%B0%D0%B4%D1%8C_-_panoramio_%281%29.jpg/360px-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B5%D0%B6%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%8F_%D0%BF%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%89%D0%B0%D0%B4%D1%8C_-_panoramio_%281%29.jpg)