Wonder Stories

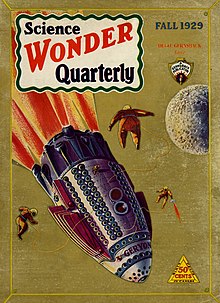

The first issue of Air Wonder Stories, July 1929. The cover is by Frank R. Paul. | |

| Publisher | Stellar Publishing |

|---|---|

| Founder | Hugo Gernsback |

| First issue | July 1929 |

| Final issue | January 1955 |

| Country | USA |

| Based in | New York City |

| Language | English |

Wonder Stories was an early American science fiction magazine which was published under several titles from 1929 to 1955. It was founded by Hugo Gernsback in 1929 after he had lost control of his first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, when his media company Experimenter Publishing went bankrupt. Within a few months of the bankruptcy, Gernsback launched three new magazines: Air Wonder Stories, Science Wonder Stories, and Science Wonder Quarterly.

Air Wonder Stories and Science Wonder Stories were merged in 1930 as Wonder Stories, and the quarterly was renamed Wonder Stories Quarterly. The magazines were not financially successful, and in 1936 Gernsback sold Wonder Stories to Ned Pines at Beacon Publications, where, retitled Thrilling Wonder Stories, it continued for nearly 20 years. The last issue was dated Winter 1955, and the title was then merged with Startling Stories, another of Pines' science fiction magazines. Startling itself lasted only to the end of 1955 before finally succumbing to the decline of the pulp magazine industry.

The editors under Gernsback's ownership were David Lasser, who worked hard to improve the quality of the fiction, and, from mid-1933, Charles Hornig. Both Lasser and Hornig published some well-received fiction, such as Stanley Weinbaum's "A Martian Odyssey", but Hornig's efforts in particular were overshadowed by the success of Astounding Stories, which had become the leading magazine in the new field of science fiction. Under its new title, Thrilling Wonder Stories was initially unable to improve its quality. For a period in the early 1940s it was aimed at younger readers, with a juvenile editorial tone and covers that depicted beautiful women in implausibly revealing spacesuits. Later editors began to improve the fiction, and by the end of the 1940s, in the opinion of science fiction historian Mike Ashley, the magazine briefly rivaled Astounding.

Publication history

[edit]By the end of the 19th century, stories centered on scientific inventions and set in the future, in the tradition of Jules Verne, were appearing regularly in popular fiction magazines.[1] Magazines such as Munsey's Magazine and The Argosy, launched in 1889 and 1896 respectively, carried a few science fiction stories each year. Some upmarket "slicks" such as McClure's, which paid well and were aimed at a more literary audience, also carried scientific stories, but by the early years of the 20th century, science fiction (though it was not yet called that) was appearing more often in the pulp magazines than in the slicks.[2][3][4] The first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, was launched in 1926 by Hugo Gernsback at the height of the pulp magazine era. It helped to form science fiction as a separately marketed genre, and by the end of the 1930s a "Golden Age of Science Fiction" had begun, inaugurated by the efforts of John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding Science Fiction. Wonder Stories was launched in the pulp era, not long after Amazing Stories, and lasted through the Golden Age and well into the 1950s.[5][6] The publisher was Stellar Publishing company based in New York City.[7]

Gernsback era

[edit]| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/6 | ||||||

| 1930 | 1/7 | 1/8 | 1/9 | 1/10 | 1/11 | |||||||

| Volume and issue numbers of Air Wonder Stories. The editor was David Lasser throughout. | ||||||||||||

Gernsback's new magazine, Amazing Stories, was successful, but Gernsback lost control of the publisher when it went bankrupt in February 1929. By April he had formed a new company, Gernsback Publications Incorporated, and created two subsidiaries: Techni-Craft Publishing Corporation and Stellar Publishing Corporation. Gernsback sent out letters advertising his plans for new magazines; the mailing lists he used almost certainly were compiled from the subscription lists of Amazing Stories. This would have been illegal, as the lists were owned by Irving Trust, the receiver of the bankruptcy. Gernsback denied using the lists under oath, but historians have generally agreed that he must have done so. The letters also asked potential subscribers to decide the name of the new magazine; they voted for "Science Wonder Stories", which became the name of one of Gernsback's new magazines.[8][9]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/6 | 1/7 | |||||

| 1930 | 1/8 | 1/9 | 1/10 | 1/11 | 1/12 | |||||||

| Volume and issue numbers of Science Wonder Stories. The editor was David Lasser throughout. | ||||||||||||

Gernsback's recovery from the bankruptcy judgment was remarkably quick. By early June he had launched three new magazines, two of which published science fiction.[10] The June 1929 issue of Science Wonder Stories appeared on newsstands on 5 May 1929, and was followed on 5 June by the July 1929 issue of Air Wonder Stories.[8][11] Both magazines were monthly, with Gernsback as editor-in-chief and David Lasser as editor.[12][13][14] Lasser had no prior editing experience and knew little about science fiction, but his recently acquired degree from MIT convinced Gernsback to hire him.[15]

Gernsback claimed that science fiction was educational. He repeatedly made this assertion in Amazing Stories, and continued to do so in his editorials for the new magazines, stating, for example, that "teachers encourage the reading of this fiction because they know that it gives the pupil a fundamental knowledge of science and aviation."[16] He also recruited a panel of "nationally known educators [who] pass upon the scientific principles of all stories". Science fiction historian Everett Bleiler describes this as "fakery, pure and simple", asserting that there is no evidence that the men on the panel—some of whom, such as Lee De Forest, were well-known scientists—had any editorial influence.[17] However, Donald Menzel, the astrophysicist on the panel, said that Gernsback sent him manuscripts and made changes to stories as a result of Menzel's commentary.[18]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 2/5 | 2/6 | 2/7 | |||||

| 1931 | 2/8 | 2/9 | 2/10 | 2/11 | 2/12 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 3/5 | 3/6 | 3/7 |

| 1932 | 3/8 | 3/9 | 3/10 | 3/11 | 3/12 | 4/1 | 4/2 | 4/3 | 4/4 | 4/5 | 4/6 | 4/7 |

| 1933 | 4/8 | 4/9 | 4/10 | 4/11 | 4/12 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 5/5 | ||

| 1934 | 5/6 | 5/7 | 5/8 | 5/9 | 5/10 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | 6/5 | 6/6 | 6/7 |

| 1935 | 6/8 | 6/9 | 6/10 | 6/11 | 6/12 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 7/4 | 7/5 | 7/6 | |

| 1936 | 7/7 | 7/8 | ||||||||||

| Issues of Wonder Stories from the merger of Science Wonder and Air Wonder to the acquisition by Beacon Publications, indicating editors: Lasser (blue, 1930–1933), and Hornig (yellow, 1933–1936) | ||||||||||||

In 1930, Gernsback decided to merge Science Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories into Wonder Stories. The reason for the merger is unknown, although it may have been that he needed the space in the printing schedule for his new Aviation Mechanics magazine.[19] Bleiler has suggested that the merger was caused by poor sales and a consequent need to downsize. In addition, Air Wonder Stories was probably focused on too specialized a niche to succeed.[11] In an editorial just before Science Wonder Stories changed its name, Gernsback commented that the word "Science" in the title "has tended to retard the progress of the magazine, because many people had the impression that it is a sort of scientific periodical rather than a fiction magazine".[20] Ironically, the inclusion of "science" in the title was the reason that science fiction writer Isaac Asimov began reading the magazine; when he saw the August 1929 issue he obtained permission to read it from his father on the grounds that it was clearly educational.[21] Concerns about the marketability of titles seem to have surfaced in the last two issues of Science Wonder, which had the word "Science" printed in a color that made it difficult to read. On the top of the cover appeared the words "Mystery-Adventure-Romance", the last of which was a surprising way to advertise a science fiction magazine.[8]

The first issue of the merged magazine appeared in June 1930, still on a monthly schedule, with Lasser as editor.[13][14] The volume numbering continued that of Science Wonder Stories, therefore Wonder Stories is sometimes regarded as a retitling of Science Wonder Stories.[22] Gernsback had also produced a companion magazine for Science Wonder Stories, titled Science Wonder Quarterly, the first issue of which was published in the fall of 1929. Three issues were produced under this title, but after the merger Gernsback changed the companion magazine's title to Wonder Stories Quarterly, and produced a further eleven issues under that title.[23][24]

| Winter | Spring | Summer | Fall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | 1/1 | |||||||||||

| 1930 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 2/1 | ||||||||

| 1931 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 3/1 | ||||||||

| 1932 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 4/1 | ||||||||

| 1933 | 4/2 | |||||||||||

| Science Wonder Quarterly (first three issues) and Wonder Stories Quarterly (all subsequent issues). The editor was David Lasser throughout. | ||||||||||||

In July 1933, Gernsback dismissed Lasser as editor. Lasser had become active in promoting workers' rights and was spending less time on his editorial duties. According to Lasser, Gernsback told him "if you like working with the unemployed so much, I suggest you go and join them".[25] It is likely that cost-cutting was also a consideration, as Lasser was paid $65 per week, a substantial salary in those days.[26][27] Soon after Lasser was let go, Gernsback received a fanzine, The Fantasy Fan, from a reader, Charles Hornig. Gernsback called Hornig to his office to interview him for the position of editor; Hornig turned out to be only 17, but Gernsback asked him to proofread a manuscript and decided that the results were satisfactory. Hornig was hired at an initial salary of $20 per week.[28][29] That same year, Gernsback dissolved Stellar Publications and created Continental Publications as the new publisher for Wonder Stories.[28] The schedule stuttered for the first time, missing the July and September 1933 issues;[28] the recent bankruptcy of the company's distributor, Eastern Distributing Corporation, may have been partly responsible for this disruption.[30][31] The first issue with Continental on the masthead, and the first listing Hornig as editor, was November 1933.[28]

Wonder Stories had a circulation of about 25,000 in 1934, comparable to that of Amazing Stories, which had declined from an early peak of about 100,000.[32][33] Gernsback considered issuing a reprint magazine in 1934, Wonder Stories Reprint Annual, but it never appeared.[34] That year he experimented with other fiction magazines—Pirate Stories and High Seas Adventures—but neither was successful.[35] Wonder Stories was also failing, and in November 1935 it started publishing bimonthly instead of monthly. Gernsback had a reputation for paying slowly and was therefore unpopular with many authors; by 1936 he was even failing to pay Laurence Manning, one of his most reliable authors.[36] Staff were sometimes asked to delay cashing their paychecks for weeks at a time.[37] Gernsback felt the blame lay with dealers who were returning magazine covers as unsold copies, and then selling the stripped copies at a reduced rate. To bypass the dealers, he made a plea in the March 1936 issue to his readers, asking them to subscribe, and proposing to distribute Wonder Stories solely by subscription. There was little response, and Gernsback decided to sell. He made a deal with Ned Pines of Beacon Magazines and on 21 February 1936 Wonder Stories was sold.[35]

Thrilling Wonder Stories

[edit]| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1936 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | |||||||||

| 1937 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 10/1 | 10/2 | 10/3 | ||||||

| 1938 | 11/1 | 11/2 | 11/3 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | ||||||

| 1939 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | ||||||

| 1940 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 16/1 | 16/2 | 16/3 | 17/1 | 17/2 | 17/3 | 18/1 | 18/2 | 18/3 |

| 1941 | 19/1 | 19/2 | 19/3 | 20/1 | 20/2 | 20/3 | 21/1 | 21/2 | ||||

| 1942 | 21/3 | 22/1 | 22/2 | 22/3 | 23/1 | 23/2 | ||||||

| 1943 | 23/3 | 24/1 | 24/2 | 24/3 | 25/1 | |||||||

| 1944 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 26/1 | 26/2 | ||||||||

| 1945 | 26/3 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/3 | ||||||||

| Issues of Thrilling Wonder Stories from 1936 to 1945. Editors are Mort Weisinger (green, 1936–1941), Oscar Friend (pink, 1941–1944), and Sam Merwin (purple, 1945). Underlining indicates that an issue was titled as a quarterly (e.g. "Winter 1944") rather than as a monthly. | ||||||||||||

Pines' magazines included several with "Thrilling" in the title, such as Thrilling Detective and Thrilling Love Stories. These were run by Leo Margulies, who had hired Mort Weisinger (among others) as the workload increased in the early 1930s. Weisinger was already an active science fiction fan, and when Wonder Stories was acquired, Margulies involved him in the editorial work. Margulies' group worked as a team, with Margulies listed as editor-in-chief on the magazines and having final say. However, since Weisinger knew science fiction well, Weisinger was quickly given more leeway, and bibliographers generally list Weisinger as the editor for this period of the magazine's history.[38]

The title was changed to Thrilling Wonder Stories to match the rest of the "Thrilling" line. The first issue appeared in August 1936—four months after the last Gernsback Wonder Stories appeared.[14][38] Wonder Stories had been monthly until the last few Gernsback issues; Thrilling Wonder was launched on a bimonthly schedule.[14] In February 1938 Weisinger asked for reader feedback regarding the idea of a companion magazine; the response was positive, and in January 1939 the first issue of Startling Stories appeared, alternating months with Thrilling Wonder.[39] A year later Thrilling Wonder went monthly; this lasted fewer than eighteen months, and the bimonthly schedule resumed after April 1941. Weisinger left that summer and was replaced at both Startling and Thrilling Wonder by Oscar J. Friend, a pulp writer with more experience in Westerns than science fiction, though he had published a novel, The Kid from Mars, in Startling Stories just the year before.[40] In mid-1943 both magazines went to a quarterly schedule, and at the end of 1944 Friend was replaced in his turn by Sam Merwin, Jr. The quarterly schedule lasted until well after World War II ended: Thrilling Wonder returned to a bimonthly schedule with the December 1946 issue and again alternated with Startling which went bimonthly in January 1947.[14][41] Merwin left in 1951 in order to become a freelance editor,[42] and was replaced by Samuel Mines, who had worked for Ned Pines since 1942.[43]

The Thrilling Wonder logo, a winged man against the background of a glass mountain was taken from the Noel Loomis story, "The Glass Mountain."

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1946 | 28/1 | 28/2 | 28/3 | 29/1 | 29/2 | |||||||

| 1947 | 29/3 | 30/1 | 30/2 | 30/3 | 31/1 | 31/2 | ||||||

| 1948 | 31/3 | 32/1 | 32/2 | 32/3 | 33/1 | 33/2 | ||||||

| 1949 | 33/3 | 34/1 | 34/2 | 34/3 | 35/1 | 35/2 | ||||||

| 1950 | 35/3 | 36/1 | 36/2 | 36/3 | 37/1 | 37/2 | ||||||

| 1951 | 37/3 | 38/1 | 38/2 | 38/3 | 39/1 | 39/2 | ||||||

| 1952 | 39/3 | 40/1 | 40/2 | 40/3 | 41/1 | 41/2 | ||||||

| 1953 | 41/3 | 42/1 | 42/2 | 42/3 | 43/1 | |||||||

| 1954 | 43/2 | 43/3 | 44/1 | 44/2 | ||||||||

| 1955 | 44/3 | |||||||||||

| Issues of Thrilling Wonder Stories from 1946 to 1955. Editors are Sam Merwin (purple, 1946–1951), Samuel Mines (orange, 1951–1954), and Alexander Samalman (gray, 1954–1955). Underlining indicates that an issue was titled as a quarterly (e.g. "Winter 1946") rather than as a monthly. | ||||||||||||

By the summer of 1949 Street & Smith, one of the largest pulp publishers, had shut down every one of their pulps. This format was dying out, though it took several more years before the pulps completely disappeared from the newsstands.[44] Both Thrilling Wonder and Startling went quarterly in 1954, and at the end of that year Mines left. The magazines did not survive him for long; only two more issues of Thrilling Wonder appeared, both edited by Alexander Samalman. After the beginning of 1955, Thrilling Wonder was merged with Startling, which itself ceased publication at the end of 1955.[45]

After the demise of Thrilling Wonder Stories the old Wonder Stories title was revived for two issues, published in 1957 and 1963. These were both edited by Jim Hendryx Jr. They were numbered vol. 45, no. 1 and 2, continuing the volume numbering of Thrilling Wonder. Both were selections from past issues of Thrilling Wonder; the second one convinced Ned Pines, the publisher who had bought Wonder Stories from Gernsback in 1936 and who still owned the rights to the stories, to start a reprint magazine called Treasury of Great Science Fiction Stories in 1964; a companion, Treasury of Great Western Stories, was added the next year.[46][47]

In 2007, Winston Engle published a new magazine in book format, titled Thrilling Wonder Stories, with a cover date of Summer 2007.[48] Engle commented that it was "not a pastiche or nostalgia exercise as much as modern SF with the entertainment, inspirational value, and excitement of the golden age".[49] A second volume appeared in 2009.[50]

IF —!: a picture feature

[edit]Six months after the debut of Thrilling Wonder Stories, its June 1937 issue contained a picture feature by Jack Binder entitled IF —!.[51] Binder's earlier training as a fine artist[52] helped him create detailed renderings of space ships, lost cities, future cities, landscapes, indigenous peoples, and even ancient Atlantins. IF —!'s pen and ink drawings are hand-lettered and rendered in black and white. These one-to-two page studies presented readers with possible outcomes to early 20th-century scientific quandaries. These included:

- IF Another Ice Age Grips the Earth![53] (June 1937) – Binder's first picture feature is tucked in between "The Chessboard of Mars" by Eando Binder and J. Harvey Haggard's "Renegade: The Ways of the Ether are Strange When a Spaceman Seeks to Betray." Ice Age offered renderings of glaciated cities, infra-red ray guns, and a floating city alongside underground habitations—"the safest and most practicable retreat!" for chilly humans. It ends with the announcement: "Next Issue: If Atomic Power were Harnessed!"

- IF the Oceans Dried![54] (April 1938) – Sailing vessels are museum pieces enshrined in huge bubble cases since the ocean floor is now home to meandering train tracks. All manner of minerals are mined to the benefit of mankind and the lost city of Atlantis (if real) is exposed. All ocean life becomes extinct and the Earth's climate undergoes dramatic, yet positive, change.

- IF Science Reached the Earth's Core[55] (Oct. 1938) – Neutronium allows humans to penetrate to the Earth's core, which is not molten, but a gravity-free haven where "vacationers enjoy the thrill of being weightless." IF —! is credited with the first use of the phrase "zero-gravity," a science fiction mainstay,[56] where "Space Travel is solved. Starting at the zero-gravity of Earth's core, accumulative acceleration is easily built up in a four-thousand-mile tube. The ship's reach Earth's surface where gravitation !|is strongest with an appreciable velocity that makes the take-off a simple process of continuation!"

- IF Earth's Axis Shifted[57] (April 1940) – An astronomical telescope points towards the night sky revealing that the planets have aligned and caused the Earth's axis to shift. Tidal waves sweep cities away. North America in now a tropic zone, while Siberia is balmy and Antarctica swarms with immigrants wanting to harvest the now accessible coal and metal. "Next Issue: IF the World were Ruled by Intelligent Robots!"

Contents and reception

[edit]

When Air Wonder Stories was launched in the middle of 1929 there were already pulp magazines such as Sky Birds and Flying Aces which focused on aerial adventures. Gernsback's first editorial dismissed these as being of the "purely 'Wild West'-world war adventure-sky busting type".[58] By contrast, Gernsback said he planned to fill Air Wonder solely with "flying stories of the future, strictly along scientific-mechanical-technical lines, full of adventure, exploration and achievement."[58] Non-fiction material on aviation was printed, including quizzes, short popular articles, and book reviews. The letters column made it clear that the readership comprised more science fiction fans than aviation fans, and Gernsback later commented that the overlap with Science Wonder readers was 90% (a figure that presumably referred only to the subscription base, not to newsstand sales).[11]

Gernsback frequently ran reader contests,[59] one of which, announced in the February 1930 issue of Air Wonder Stories, asked for a slogan for the magazine. John Wyndham, later to become famous as the author of The Day of the Triffids, won with "Future Flying Fiction", submitted under his real name of John Beynon Harris. Later that year a contest in Science Wonder Quarterly asked readers for an answer to the question "What I Have Done to Spread Science Fiction". The winner was Raymond Palmer who later became editor of Gernsback's original magazine, Amazing Stories. He won the contest for his role in founding a "Science Correspondence Club".[60]

Science Wonder's first issue included the first part of a serial, The Reign of the Ray, by Fletcher Pratt and Irwin Lester, and short stories by Stanton Coblentz and David H. Keller. Air Wonder began with a reprinted serial, Victor MacClure's Ark of the Covenant. Writers who first appeared in the pages of these magazines include Neil R. Jones, Ed Earl Repp, Raymond Z. Gallun and Lloyd Eshbach.[61] The quality of published science fiction at the time was generally low, and Lasser was keen to improve it. On 11 May 1931 he wrote to his regular contributors to tell them that their science fiction stories "should deal realistically with the effect upon people, individually and in groups, of a scientific invention or discovery. ... In other words, allow yourself one fundamental assumption—that a certain machine or discovery is possible—and then show what would be its logical and dramatic consequences upon the world; also what would be the effect upon the group of characters that you pick to carry your theme."[62]

After the merger

[edit]Lasser provided ideas to his authors and commented on their drafts, attempting to improve both the level of scientific literacy and the quality of the writing.[63] Some of his correspondence has survived, including an exchange with Jack Williamson, whom Lasser commissioned in early 1932 to write a story based on a plot provided by a reader—the winning entry in one of the magazine's competitions. Lasser emphasized to Williamson the importance of scientific plausibility, citing as an example a moment in the story where the earthmen have to decipher a written Martian language: "You must be sure and make it convincing how they did it; for they have absolutely no method of approach to a written language of another world."[64] On one occasion Lasser's work with his authors extended to collaboration: "The Time Projector", a story which appeared in the July 1931 issue of Wonder Stories, was credited to David H. Keller and David Lasser.[63] Both Lasser and, later, Hornig, were given almost complete editorial freedom by Gernsback, who reserved only the right to give final approval to the contents. This was in contrast to the more detailed control Gernsback had exerted over the content of Amazing Stories in the first years of its existence. Science fiction historian Sam Moskowitz has suggested that the reason was the poor financial state of Wonder Stories—Gernsback perhaps avoided corresponding with authors as he owed many of them money.[65][66]

Lasser allowed the letter column to become a free discussion of ideas and values, and published stories dealing with topics such as the relationship between the sexes. One such story, Thomas S. Gardner's "The Last Woman", portrayed a future in which men, having evolved beyond the need for love, keep the last woman in a museum. In "The Venus Adventurer", an early story by John Wyndham, a spaceman corrupts the innocent natives of Venus. Lasser avoided printing space opera, and several stories from Wonder in the early 1930s were more realistic than most contemporary space fiction. Examples include Edmond Hamilton's "A Conquest of Two Worlds", P. Schuyler Miller's "The Forgotten Man of Space", and several stories by Frank K. Kelly, including "The Moon Tragedy".[67]

Lasser was one of the founders of the American Rocket Society which, under its initial name of the "Interplanetary Society", announced its existence in the pages of the June 1930 Wonder Stories.[68] Several of Wonder's writers were also members of the Interplanetary Society, and perhaps as a consequence of the relationship Wonder Stories Quarterly began to focus increasingly on fiction with interplanetary settings. A survey of the last eight issues of Wonder Stories Quarterly by Bleiler found almost two-thirds of the stories were interplanetary adventures, while only a third of the stories in the corresponding issues of Wonder Stories could be so described. Wonder Stories Quarterly added a banner reading "Interplanetary Number" to the cover of the Winter 1931 issue, and retained it, as "Interplanetary Stories", for subsequent issues.[24] Lasser and Gernsback were also briefly involved with the fledgling Technocracy movement. Gernsback published two issues of Technocracy Review, which Lasser edited, commissioning stories based on technocratic ideas from Nat Schachner. These appeared in Wonder Stories during 1933, culminating in a novel, The Revolt of the Scientists.[69][70]

Reviews of fiction and popular science books were published, and there was a science column which endeavored to answer readers' questions. These features were at first of good quality, but deteriorated after Lasser's departure, although it is not certain that Lasser wrote the content of either one. An influential non-fiction initiative was the creation of the Science Fiction League, an organization that brought together local science fiction fan clubs across the country. Gernsback took the opportunity to sell items such as buttons and insignia, and it was undoubtedly a profitable enterprise for him as well as a good source of publicity. It was ultimately more important in becoming one of the foundations of science fiction fandom.[22][71]

Hornig

[edit]When Hornig took over from Lasser at the end of 1933 he attempted to continue and expand Lasser's approach. Hornig introduced a "New Policy" in the January 1934 issue, emphasizing originality and barring stories that merely reworked well-worn ideas.[72] He asked for stories that included good science, although "not enough to become boring to those readers who are not primarily interested in the technicalities of the science".[22] However, Astounding was moving into the lead position in the science fiction magazine field at this time, and Hornig had difficulty in competing. His rates of payment were lower than Astounding's one cent per word; sometimes his writers were paid very late, or not at all. Despite these handicaps, Hornig managed to find some good material, including Stanley G. Weinbaum's "A Martian Odyssey", which appeared in the July 1934 Wonder and has been frequently reprinted.[72]

In the December 1934 – January 1935 issue of Hornig's fanzine, Fantasy Magazine, he took the unusual step of listing several stories that he had rejected as lacking novelty, but which had subsequently appeared in print in other magazines. The list includes several by successful writers of the day, such as Raymond Z. Gallun and Miles Breuer. The most prominent story named is Triplanetary by E. E. Smith, which appeared in Amazing.[22]

Both Lasser and Hornig printed fiction translated from French and German writers, including Otfrid von Hanstein and Otto Willi Gail. With the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany in the 1930s a few readers (including Donald Wollheim) wrote letters complaining about the inclusion of German stories. The editorial response was a strong defense of the translations; Gernsback argued that events in Germany were irrelevant to the business of selecting fiction.[73]

The covers for almost every issue of Air Wonder, Science Wonder, Wonder Stories and Wonder Stories Quarterly were painted by Frank R. Paul, who had followed Gernsback from Amazing Stories. The only exception was a cover image composed of colored dots, which appeared on the November 1932 issue.[14][74]

Weisinger and Friend

[edit]When the magazine moved to Beacon Publications, as Thrilling Wonder, the fiction began to focus more on action than on ideas. The covers, often by Earle K. Bergey, typically depicted bizarre aliens and damsels in distress. In 1939, a reader, Martin Alger, coined the phrase "bug-eyed monster" to describe one such cover; the phrase subsequently entered the dictionary as a word for an alien. Several well-known writers contributed, including Ray Cummings, and John W. Campbell, whose "Brain-Stealers of Mars" series began in Thrilling Wonder in the December 1936 issue. A comic-strip began in August 1936, the first issue of the Beacon Publications version. It was illustrated and possibly written by Max Plaisted.[75] The strip, titled Zarnak, was not a success, and was cancelled after eight issues.[76]

Weisinger's successor, Friend, gave the magazine a significantly more juvenile feel. He used the alias "Sergeant Saturn" and was generally condescending to the readers; this may not have been his fault as Margulies, who was still the editorial director, probably wanted him to attract a younger readership. Under Friend's direction, Earle K. Bergey transformed the look of Thrilling Wonder Stories by foregrounding human figures in space, focusing on the anatomy of women in implausibly revealing spacesuits and his trademark "brass brassières".[77]

Merwin and Mines

[edit]Merwin, who took over with the Winter 1945 issue, adopted a more mature approach than Friend's. He obtained fiction from writers who had previously been publishing mainly in John Campbell's Astounding. The Summer 1945 issue of Thrilling Wonder included Jack Vance's first published story, "The World Thinker". Merwin also published several stories by Ray Bradbury, some of which were later included in Bradbury's collection The Martian Chronicles. Other well-known writers that Merwin was able to attract included Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, and Robert A. Heinlein. Thrilling Wonder often published intelligent, thoughtful stories, some of which Campbell would have been unlikely to accept at Astounding: he did not like to publish stories that showed the negative consequences of scientific advances such as nuclear power. In the opinion of science fiction historian Mike Ashley, during the late 1940s Thrilling Wonder became a serious rival to Astounding's long domination of the field.[78] However, this is not a universal opinion, as the magazine is elsewhere described during Merwin's tenure as "evidently secondary to Startling".[79]

Samuel Mines took over from Merwin at the end of 1951, both at Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder.[45][80] He argued against restrictions in science fiction themes, and in 1952 published Philip José Farmer's "The Lovers", a ground-breaking story about inter-species sex, in Startling. He followed this in 1953 with another taboo-breaking story from Farmer, "Mother", in Thrilling Wonder, in which a spaceman makes his home in an alien womb.[79][81][82] In the December 1952 Thrilling Wonder, Mines published Edmond Hamilton's "What's It Like Out There?", a downbeat story about the realities of space exploration that had been considered too bleak for publication when it had originally been written in the 1930s. Sherwood Springer's "No Land of Nod", in the same issue, dealt with incest between a father and his daughter in a world in which they are the only two survivors. These stories were all well received by the readership.[81]

Influence on the field

[edit]For a few years, Lasser was the dominant force in American science fiction.[83] Under him, Wonder Stories was the best of the science fiction magazines of the early 1930s,[84] and the most successful of all Gernsback's forays into the field.[46] Lasser shaped a new generation of writers, who in many cases had no prior writing experience of any kind; Wonder Stories was part of a "forcing ground", according to Isaac Asimov, where young writers learned their trade. The magazine was less constrained by pulp convention than its competitors, and published some novels such as Eric Temple Bell's The Time Stream and Festus Pragnell's The Green Man of Graypec, which were not in the mainstream of development of the science fiction genre.[22]

As Thrilling Wonder the magazine was much less influential. Until the mid-1940s it was focused on younger readers, and by the time Merwin and Mines introduced a more adult approach, Astounding Science Fiction had taken over as the unquestioned leader of the field. Thrilling Wonder could not compete with John Campbell and the Golden Age of science fiction that he brought into being, but it did periodically publish good stories. In the end it was unable to escape its roots in the pulp industry, and died in the carnage that swept away every remaining pulp magazine in the 1950s.[79]

Publication details

[edit]

The editorial duties at Wonder Stories and its related magazines were not always performed by the person who bore the title of "editor" in the magazine's masthead. From the beginning until the sale to Beacon Publications, Gernsback was listed as editor-in-chief; Lasser was variously listed as "literary editor" and "managing editor", while Hornig was always listed as "managing editor".[85][86][87] Similarly, under Beacon Publications, the nominal editor (initially Leo Margulies) was not always the one to work on the magazine.[38] The following list shows who actually performed the editorial duties. More details are given in the publishing history section, above, which focuses on when the editors involved actually obtained control of the magazine contents, instead of when their names appeared on the masthead.

- Air Wonder Stories

- David Lasser (July 1929 – May 1930)[85]

- Science Wonder Stories

- David Lasser (June 1929 – May 1930)[86]

- Science Wonder Quarterly

- David Lasser (Fall 1929 – Spring 1930)[23]

- Wonder Stories

- Wonder Stories Quarterly

- David Lasser (Summer 1930 – Winter 1933)[24]

- Thrilling Wonder Stories

The publisher only changed once through the lifetime of the magazine, when Gernsback sold Wonder Stories in 1936. However, Gernsback changed the name of his company from Stellar Publishing Corporation to Continental Publications, Incorporated, with effect from December 1933. Thrilling Wonder's publisher went by three names: Beacon Publications initially, then Better Publications from the August 1937 issue, and finally, starting with the Fall 1943 issue, Standard Magazines.[85][86][87][88]

Gernsback experimented with the price and format, looking for a profitable combination. Both Air Wonder and Science Wonder were bedsheet-sized (8.5 × 11.75 in, or 216 × 298 mm) and priced at 25 cents, as were the first issues of Wonder Stories. With the November 1930 issue Wonder Stories changed to pulp format, 6.75 × 9.9 in (171 × 251 mm). It reverted to bedsheet after a year, and then in November 1933 became a pulp magazine for good. The pulp issues all had 144 pages; the bedsheet issues generally had 96 pages, though five issues from November 1932 to March 1933 had only 64 pages. Those five issues coincided with a price cut to 15 cents, which was reversed with the April 1933 issue. Gernsback cut the price to 15 cents again from June 1935 until the sale to Beacon Publications in 1936, though this time he did not reduce the page count. The short duration of these price cuts suggests Gernsback rapidly realized that the additional circulation they gained him cost too much in lost revenue.[85][86][87] Under Beacon Publications Thrilling Wonder remained pulp-sized throughout.[88]

There were two British reprint editions of Thrilling Wonder. The earlier edition, from Atlas Publishing, produced three numbered issues from 1949 to 1950, and a further seven from 1952 to 1953. Another four issues appeared from Pemberton between 1953 and 1954; these were numbered from 101 to 104. There were Canadian editions in 1945–1946 and 1948–1951.[79]

References

[edit]- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 7.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 21–25.

- ^ Nicholls, "Pulp Magazines", p. 979.

- ^ Ashley, Transformations, p. 155.

- ^ Stableford, "Amazing Stories", p. 27.

- ^ Nicholls, "Golden Age of SF", p. 258.

- ^ H. W. Hall, ed. (1983). The Science Fiction Magazine Checklist (PDF). Bryan, TX. p. 10. ISBN 0-935064-10-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Bleiler, Gernsback Years, pp. 579–581.

- ^ Perry, "An Amazing Story" pp. 114–115.

- ^ The other was Radio-Craft, which was aimed at radio hobbyists and repairmen. See Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 579.

- ^ a b c Bleiler, Gernsback Years, pp. 541–543.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 64.

- ^ a b Ashley, Time Machines, p. 237.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ashley, Time Machines, p. 254.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 47.

- ^ Gernsback, editorial in Air Wonder Stories, July 1929, p. 5, quoted in Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 542.

- ^ Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 580.

- ^ Carter, Creation of Tomorrow, p. 11.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Gernsback, in Science Wonder, May 1930, p. 1099; quoted in Ashley, Time Machines, p. 71.

- ^ Asimov, Before the Golden Age I, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e Bleiler, Gernsback Years, pp. 586–589.

- ^ a b Bleiler, Gernsback Years, pp. 578–579.

- ^ a b c Bleiler, Gernsback Years, pp. 595–596.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 57.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 57. Bleiler, who cites Davin, gives Lasser's salary as $70 per week, though he does not explain the discrepancy; see Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 588.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 94, note 38.

- ^ a b c d Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 70.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 29.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 43.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 51.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Tuck, Encyclopedia of SF, Vol. 3, p. 609.

- ^ a b Ashley, Time Machines, p. 91.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 64.

- ^ Hornig, quoted in Davin, Pioneers, p. 68; Hornig does not specify whether this happened only towards the end of Gernsback's control of the magazine.

- ^ a b c Ashley, Time Machines, p. 100.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 136.

- ^ Clute & Edwards, "Oscar J. Friend", p. 454.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 250.

- ^ Edwards, "Sam Merwin Jr.", p. 801.

- ^ Edwards, "Samuel Mines", p. 811.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Ashley, Transformations, p. 345.

- ^ a b Nicholls & Stableford, "Wonder Stories", p. 1346.

- ^ Ashley, Transformations, p. 221.

- ^ Engle, Thrilling Wonder Stories Summer 2007

- ^ Ansible 239, June 2007, David Langford, retrieved November 29, 2008

- ^ Engle, Thrilling Wonder Stories Volume 2

- ^ Nahin, Paul (1999). Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics, and Science Fiction. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 261. ISBN 0-387-98571-9.

- ^ Hamerlinck, P.C. (2001). Fawcett Companion: The Best of FCA. Raleigh, NC: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 1-893905-10-1.

- ^ Binder, Jack (June 1937). "IF Another Ice Age Grips the Earth!". Thrilling Wonder Stories. 9 (3): 87.

- ^ Binder, Jack (April 1938). "IF The Oceans Dried!". Thrilling Wonder Stories. 11 (2): 104–105.

- ^ Binder, Jack (October 1938). "IF Science Reached the Earth's Core!". Thrilling Wonder Stories. 12 (3): 98–99.

- ^ Joyce, C. Allen (2009). Under the Covers and Between the Sheets: The Inside Story behind classic characters, authors, unforgettable phrases, and unexpected endings. New York: Penguin. pp. np. ISBN 978-1-60652-034-5.

- ^ Binder, Jack (April 1940). "IF Earth's Axis Shifted!". Thrilling Wonder Stories. 16 (1): 78–79.

- ^ a b Editorial in Air Wonder Stories, July 1929; quoted in Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 541.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 52.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 39.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 71–73. The quote, from a letter by Lasser dated 11 May 1931, is given by Ashley on p. 73.

- ^ a b Davin, Pioneers, p. 41.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 48.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 73–75.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 37.

- ^ Clute, "Nat Schachner", p. 1056.

- ^ Peter Roberts, "Science Fiction League", p. 1066.

- ^ a b Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Carter, Creation of Tomorrow, p. 119.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 276.

- ^ "Catalog". www.pulpartists.com. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 188–190.

- ^ a b c d Malcolm Edwards, "Thrilling Wonder Stories", pp. 1222–1223.

- ^ Ashley, Transformations, p. 343.

- ^ a b Ashley, Transformations, pp. 13–16.

- ^ Peter Nicholls, "Sex", p. 539.

- ^ Davin, Pioneers, p. 40.

- ^ Clute, Illustrated Encyclopedia, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 543.

- ^ a b c d Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 581.

- ^ a b c d e Bleiler, Gernsback Years, p. 589.

- ^ a b Tuck, Encyclopedia of SF, Vol. 3, p. 599.

Sources

[edit]- Asimov, Isaac (1978), Before the Golden Age: Volume One, London: Orbit, ISBN 0-86007-803-5

- Ashley, Mike (2000), The Time Machines:The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, ISBN 0-85323-865-0

- Ashley, Mike (2005), Transformations:The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, ISBN 0-85323-779-4

- Bleiler, Everett F. (1998), Science-Fiction: The Gernsback Years: A complete coverage of the genre magazines Amazing, Astounding, Wonder, and others from 1926 through 1936, Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, ISBN 0-87338-604-3

- Carter, Paul A. (1977), The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-04211-6

- Clute, John (1981), "Sex", in Nicholls, Peter (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, London: Granada, ISBN 0-586-05380-8

- Clute, John (1993), "Nat Schachner", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Clute, John; Edwards, Malcolm (1993), "Oscar J. Friend", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Davin, Erik Leif (1999), Pioneers of Wonder, Prometheus Books, ISBN 1-57392-702-3

- Edwards, Malcolm (1993), "Sam Merwin Jr.", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Edwards, Malcolm (1993), "Samuel Mines", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Edwards, Malcolm (1993), "Thrilling Wonder Stories", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Edwards, Malcolm; Nicholls, Peter (1993), "SF Magazines", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Engle, Winston (2007), Thrilling Wonder Stories Summer 2007, Thrilling Wonder LLC, ISBN 978-0-9796718-0-7

- Engle, Winston (2009), Thrilling Wonder Stories Volume 2, Thrilling Wonder LLC, ISBN 978-0-9796718-1-4

- Nicholls, Peter (1981), "Golden Age of SF", in Nicholls, Peter (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, London: Granada, ISBN 0-586-05380-8

- Nicholls, Peter; Stableford, Brian (1993), "Wonder Stories", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Perry, Tom "An Amazing Story: Experiment in Bankruptcy" in Amazing Science Fiction vol. 51, no 3 (May 1978)

- Roberts, Peter (1993), "Science Fiction League", in Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Stableford, Brian (1981), "Amazing Stories", in Nicholls, Peter (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, London: Granada, ISBN 0-586-05380-8

- Tuck, Donald H. (1982), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3, Chicago: Advent: Publishers, Inc., ISBN 0-911682-26-0

External links

[edit]- Wonder Stories

- Pulp magazines

- Magazines established in 1929

- Magazines disestablished in 1955

- Defunct science fiction magazines published in the United States

- Science fiction magazines established in the 1920s

- Magazines published by Hugo Gernsback

- 1929 establishments in New York (state)

- 1955 disestablishments in New York (state)

- Defunct magazines published in New York City