John Maynard Keynes

The Lord Keynes | |

|---|---|

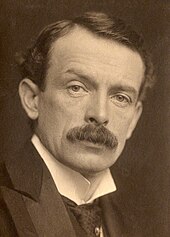

Keynes in 1933 | |

| Born | 5 June 1883 Cambridge, England |

| Died | 21 April 1946 (aged 62) Tilton, near Firle in Sussex, England |

| Education | |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | |

| Parents |

|

| Academic career | |

| Field | |

| Institution | King's College, Cambridge |

| School or tradition | Keynesian economics |

| Influences | |

| Contributions | |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| In office 7 July 1942 – 21 April 1946 Hereditary peerage | |

| Succeeded by | Peerage abolished |

| Preceded by | Peerage created |

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes[3] CB, FBA (/keɪnz/ KAYNZ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in mathematics, he built on and greatly refined earlier work on the causes of business cycles.[4] One of the most influential economists of the 20th century,[5][6][7] he produced writings that are the basis for the school of thought known as Keynesian economics, and its various offshoots.[8] His ideas, reformulated as New Keynesianism, are fundamental to mainstream macroeconomics. He is known as the "father of macroeconomics".[9]

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Keynes spearheaded a revolution in economic thinking, challenging the ideas of neoclassical economics that held that free markets would, in the short to medium term, automatically provide full employment, as long as workers were flexible in their wage demands. He argued that aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) determined the overall level of economic activity, and that inadequate aggregate demand could lead to prolonged periods of high unemployment, and since wages and labour costs are rigid downwards the economy will not automatically rebound to full employment.[10] Keynes advocated the use of fiscal and monetary policies to mitigate the adverse effects of economic recessions and depressions. He detailed these ideas in his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in early 1936. By the late 1930s, leading Western economies had begun adopting Keynes's policy recommendations. Almost all capitalist governments had done so by the end of the two decades following Keynes's death in 1946. As a leader of the British delegation, Keynes participated in the design of the international economic institutions established after the end of World War II but was overruled by the American delegation on several aspects.

Keynes's influence started to wane in the 1970s, partly as a result of the stagflation that plagued the British and American economies during that decade, and partly because of criticism of Keynesian policies by Milton Friedman and other monetarists,[11] who disputed the ability of government to favourably regulate the business cycle with fiscal policy.[12] The 2007–2008 financial crisis sparked the 2008–2009 Keynesian resurgence. Keynesian economics provided the theoretical underpinning for economic policies undertaken in response to the 2007–2008 financial crisis by President Barack Obama of the United States, Prime Minister Gordon Brown of the United Kingdom, and other heads of governments.[13]

When Time magazine included Keynes among its Most Important People of the Century in 1999, it reported that "his radical idea that governments should spend money they don't have may have saved capitalism".[14] The Economist has described Keynes as "Britain's most famous 20th-century economist".[15] In addition to being an economist, Keynes was also a civil servant, a director of the Bank of England, and a part of the Bloomsbury Group of intellectuals.[16]

Early life and education

[edit]

John Maynard Keynes was born in Cambridge, England, in June 1883 to an upper-middle-class family. His father, John Neville Keynes, was an economist and a lecturer in moral sciences at the University of Cambridge and his mother, Florence Ada Keynes, a local social reformer. Keynes was the firstborn and was followed by two more children – Margaret Neville Keynes in 1885 and Geoffrey Keynes in 1887. Geoffrey became a surgeon and Margaret married the Nobel Prize-winning physiologist Archibald Hill.

According to the economic historian and biographer Robert Skidelsky, Keynes's parents were loving and attentive. They attended a Congregational Church[17] and remained in the same house throughout their lives, where the children were always welcome to return. Keynes received considerable support from his father, including expert coaching to help him pass his scholarship exams and financial help both as a young man and when his assets were nearly wiped out at the onset of Great Depression in 1929. Keynes's mother made her children's interests her own, and according to Skidelsky, "because she could grow up with her children, they never outgrew home".[18]

In January 1889, at the age of five and a half, Keynes started at the kindergarten of the Perse School for Girls for five mornings a week. He quickly showed a talent for arithmetic, but his health was poor leading to several long absences. He was tutored at home by a governess, Beatrice Mackintosh, and his mother. In January 1892, at eight and a half, he started as a day pupil at St Faith's preparatory school. By 1894, Keynes was top of his class and excelling at mathematics. In 1896, St Faith's headmaster, Ralph Goodchild, wrote that Keynes was "head and shoulders above all the other boys in the school" and was confident that Keynes could get a scholarship to Eton.[19]

In 1897, Keynes won a King's Scholarship to Eton College, where he displayed talent in a wide range of subjects, particularly mathematics, classics and history: in 1901, he was awarded the Tomline Prize for mathematics. At Eton, Keynes experienced the first "love of his life" in Dan Macmillan, older brother of the future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.[20] Despite his middle-class background, Keynes mixed easily with upper-class pupils.

In 1902, Keynes left Eton for King's College, Cambridge, after receiving a scholarship for this also, to read mathematics. Alfred Marshall begged Keynes to become an economist,[21] although Keynes's own inclinations drew him towards philosophy, especially the ethical system of G. E. Moore. Keynes was elected to the University Pitt Club[22] and was an active member of the semi-secretive Cambridge Apostles society, a debating club largely reserved for the brightest students. Like many members, Keynes retained a bond to the club after graduating and continued to attend occasional meetings throughout his life. Before leaving Cambridge, Keynes became the president of the Cambridge Union Society and Cambridge University Liberal Club. He was said to be an atheist.[23][24]

In May 1904, he received a first-class BA in mathematics. Aside from a few months spent on holidays with family and friends, Keynes continued to involve himself with the university over the next two years. He took part in debates, further studied philosophy and attended economics lectures informally as a graduate student for one term, which constituted his only formal education in the subject. He took civil service exams in 1906.

The economist Harry Johnson wrote that the optimism imparted by Keynes's early life is a key to understanding his later thinking.[25] Keynes was always confident he could find a solution to whatever problem he turned his attention to and retained a lasting faith in the ability of government officials to do good.[26] Keynes's optimism was also cultural, in two senses: he was of the last generation raised by an empire still at the height of its power and was also of the last generation who felt entitled to govern by culture, rather than by expertise. According to Skidelsky, the sense of cultural unity current in Britain from the 19th century to the end of World War I provided a framework with which the well-educated could set various spheres of knowledge in relation to each other and life, enabling them to confidently draw from different fields when addressing practical problems.[18]

Career

[edit]In October 1906 Keynes began his Civil Service career as a clerk in the India Office.[27] He enjoyed his work at first, but by 1908 had become bored and resigned his position to return to Cambridge and work on probability theory, through a lectureship in economics at first funded personally by economists Alfred Marshall and Arthur Pigou; he became a fellow of King's College in 1909.[28]

By 1909 Keynes had also published his first professional economics article in The Economic Journal, about the effect of a recent global economic downturn on India.[29] He founded the Political Economy Club, a weekly discussion group. Keynes's earnings rose further as he began to take on pupils for private tuition.

In 1911 Keynes was made the editor of The Economic Journal. By 1913 he had published his first book, Indian Currency and Finance.[30] He was then appointed to the Royal Commission on Indian Currency and Finance[31] – the same topic as his book – where Keynes showed considerable talent at applying economic theory to practical problems. His written work was published under the name "J M Keynes", though to his family and friends he was known as Maynard. (His father, John Neville Keynes, was also always known by his middle name).[32]

First World War

[edit]The British Government called on Keynes's expertise during the First World War. While he did not formally rejoin the civil service in 1914, Keynes travelled to London at the government's request a few days before hostilities started. Bankers had been pushing for the suspension of specie payments – the gold equivalent of banknotes – but with Keynes's help, the Chancellor of the Exchequer (then Lloyd George) was persuaded that this would be a bad idea, as it would hurt the future reputation of the city if payments were suspended before it was necessary.

In January 1915 Keynes took up an official government position at the Treasury. Among his responsibilities were the design of terms of credit between Britain and its continental allies during the war and the acquisition of scarce currencies. According to economist Robert Lekachman, Keynes's "nerve and mastery became legendary" because of his performance of these duties, as in the case where he managed to assemble a supply of Spanish pesetas.

The secretary of the Treasury was delighted to hear Keynes had amassed enough to provide a temporary solution for the British Government. But Keynes did not hand the pesetas over, choosing instead to sell them all to break the market: his boldness paid off, as pesetas then became much less scarce and expensive.[33]

On the introduction of military conscription in 1916, he applied for exemption as a conscientious objector, which was effectively granted conditional upon continuing his government work.

In the 1917 King's Birthday Honours, Keynes was appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath for his wartime work,[34] and his success led to the appointment that had a huge effect on Keynes's life and career; Keynes was appointed financial representative for the Treasury to the 1919 Versailles peace conference. He was also appointed Officer of the Belgian Order of Leopold.[35]

Versailles peace conference

[edit]

Keynes's experience at Versailles was influential in shaping his future outlook, yet it was not a successful one. Keynes's main interest had been in trying to prevent Germany's compensation payments being set so high it would traumatise innocent German people, damage the nation's ability to pay and sharply limit its ability to buy exports from other countries – thus hurting not just Germany's economy but that of the wider world.

Unfortunately for Keynes, conservative powers in the coalition that emerged from the 1918 coupon election were able to ensure that both Keynes himself and the Treasury were largely excluded from formal high-level talks concerning reparations. Their place was taken by the Heavenly Twins – the judge Lord Sumner and the banker Lord Cunliffe, whose nickname derived from the "astronomically" high war compensation they wanted to demand from Germany. Keynes was forced to try to exert influence mostly from behind the scenes.

The three principal players at the Paris conferences were Britain's Lloyd George, France's Georges Clemenceau and America's President Woodrow Wilson.[36] It was only Lloyd George to whom Keynes had much direct access; until the 1918 election he had some sympathy with Keynes's view but while campaigning had found his speeches were well received by the public only if he promised to harshly punish Germany, and had therefore committed his delegation to extracting high payments.

Lloyd George did, however, win some loyalty from Keynes with his actions at the Paris conference by intervening against the French to ensure the dispatch of much-needed food supplies to German civilians. Clemenceau also pushed for substantial reparations, though not as high as those proposed by the British, while on security grounds, France argued for an even more severe settlement than Britain.

Wilson initially favoured relatively lenient treatment of Germany – he feared too harsh conditions could foment the rise of extremism and wanted Germany to be left sufficient capital to pay for imports. To Keynes's dismay, Lloyd George and Clemenceau were able to pressure Wilson to agree to include pensions in the reparations bill.

Towards the end of the conference, Keynes came up with a plan that he argued would not only help Germany and other impoverished central European powers but also be good for the world economy as a whole. It involved the radical writing down of war debts, which would have had the possible effect of increasing international trade all round, but at the same time thrown over two-thirds of the cost of European reconstruction on the United States.[37]

Lloyd George agreed it might be acceptable to the British electorate. However, America was against the plan; the US was then the largest creditor, and by this time Wilson had started to believe in the merits of a harsh peace and thought that his country had already made excessive sacrifices. Hence despite his best efforts, the result of the conference was a treaty which disgusted Keynes both on moral and economic grounds and led to his resignation from the Treasury.[38]

In June 1919 he turned down an offer to become chairman of the British Bank of Northern Commerce, a job that promised a salary of £2,000 in return for a morning per week of work.[citation needed]

Keynes's analysis on the predicted damaging effects of the treaty appeared in the highly influential book, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, published in 1919.[39] This work has been described as Keynes's best book, where he was able to bring all his gifts to bear – his passion as well as his skill as an economist. In addition to economic analysis, the book contained appeals to the reader's sense of compassion:

I cannot leave this subject as though its just treatment wholly depended either on our pledges or on economic facts. The policy of reducing Germany to servitude for a generation, of degrading the lives of millions of human beings, and of depriving a whole nation of happiness should be abhorrent and detestable, – abhorrent and detestable, even if it was possible, even if it enriched ourselves, even if it did not sow the decay of the whole civilized life of Europe.

— [citation needed]

Also present was striking imagery such as "year by year Germany must be kept impoverished and her children starved and crippled" along with bold predictions which were later justified by events:

If we aim deliberately at the impoverishment of Central Europe, vengeance, I dare predict, will not limp. Nothing can then delay for very long that final war between the forces of Reaction and the despairing convulsions of Revolution, before which the horrors of the late German war will fade into nothing.

— [citation needed]

Keynes's followers assert that his predictions of disaster were borne out when the German economy suffered the hyperinflation of 1923, and again by the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the outbreak of the Second World War. However, historian Ruth Henig claims that "most historians of the Paris peace conference now take the view that, in economic terms, the treaty was not unduly harsh on Germany and that, while obligations and damages were inevitably much stressed in the debates at Paris to satisfy electors reading the daily newspapers, the intention was quietly to give Germany substantial help towards paying her bills, and to meet many of the German objections by amendments to the way the reparations schedule was in practice carried out".[40][41]

Only a small fraction of reparations was ever paid. In fact, historian Stephen A. Schuker demonstrates in American 'Reparations' to Germany, 1919–33, that the capital inflow from American loans substantially exceeded German out payments so that, on a net basis, Germany received support equal to four times the amount of the post-Second World War Marshall Plan.[42]

Schuker also shows that, in the years after Versailles, Keynes became an informal reparations adviser to the German government, wrote one of the major German reparation notes, and supported hyperinflation on political grounds. Nevertheless, The Economic Consequences of the Peace gained Keynes international fame, even though it also caused him to be regarded as anti-establishment – it was not until after the outbreak of the Second World War that Keynes was offered a directorship of a major British Bank, or an acceptable offer to return to government with a formal job. However, Keynes was still able to influence government policy-making through his network of contacts, his published works and by serving on government committees; this included attending high-level policy meetings as a consultant.[38]

In the 1920s

[edit]Keynes had completed his A Treatise on Probability before the war but published it in 1921.[38] The work was a notable contribution to the philosophical and mathematical underpinnings of probability theory, championing the important view that probabilities were no more or less than truth values intermediate between simple truth and falsity. Keynes developed the first upper-lower probabilistic interval approach to probability in chapters 15 and 17 of this book, as well as having developed the first decision weight approach with his conventional coefficient of risk and weight, c, in chapter 26. In addition to his academic work, the 1920s saw Keynes active as a journalist selling his work internationally and working in London as a financial consultant. In 1924 Keynes wrote an obituary for his former tutor Alfred Marshall which Joseph Schumpeter called "the most brilliant life of a man of science I have ever read".[43] Mary Paley Marshall was "entranced" by the memorial, while Lytton Strachey rated it as one of Keynes's "best works".[38]

In 1922 Keynes continued to advocate reduction of German reparations with A Revision of the Treaty.[38] He attacked the post-World War I deflation policies with A Tract on Monetary Reform in 1923[38] – a trenchant argument that countries should target stability of domestic prices, avoiding deflation even at the cost of allowing their currency to depreciate. Britain suffered from high unemployment through most of the 1920s, leading Keynes to recommend the depreciation of sterling to boost jobs by making British exports more affordable. From 1924 he was also advocating a fiscal response, where the government could create jobs by spending on public works.[38] During the 1920s Keynes's pro-stimulus views had only limited effect on policymakers and mainstream academic opinion – according to Hyman Minsky one reason was that at this time his theoretical justification was "muddled".[29] The Tract had also called for an end to the gold standard. Keynes advised it was no longer a net benefit for countries such as Britain to participate in the gold standard, as it ran counter to the need for domestic policy autonomy. It could force countries to pursue deflationary policies at exactly the time when expansionary measures were called for to address rising unemployment. The Treasury and Bank of England were still in favour of the gold standard and in 1925 they were able to convince the then Chancellor Winston Churchill to re-establish it, which had a depressing effect on British industry. Keynes responded by writing The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill and continued to argue against the gold standard until Britain finally abandoned it in 1931.[38]

During the Great Depression

[edit]

Keynes had begun a theoretical work to examine the relationship between unemployment, money and prices back in the 1920s.[44] The work, Treatise on Money, was published in 1930 in two volumes. A central idea of the work was that if the amount of money being saved exceeds the amount being invested – which can happen if interest rates are too high – then unemployment will rise. This is in part a result of people not wanting to spend too high a proportion of what employers pay out, making it difficult, in aggregate, for employers to make a profit. Another key theme of the book is the unreliability of financial indices for representing an accurate – or indeed meaningful – indication of general shifts in purchasing power of currencies over time. In particular, he criticised the justification of Britain's return to the gold standard in 1925 at pre-war valuation by reference to the wholesale price index. He argued that the index understated the effects of changes in the costs of services and labour.

Keynes was deeply critical of the British government's austerity measures during the Great Depression. He believed that budget deficits during recessions were a good thing and a natural product of an economic slump. He wrote, "For Government borrowing of one kind or another is nature's remedy, so to speak, for preventing business losses from being, in so severe a slump as the present one, so great as to bring production altogether to a standstill."[45]

At the height of the Great Depression, in 1933, Keynes published The Means to Prosperity, which contained specific policy recommendations for tackling unemployment in a global recession, chiefly counter-cyclical public spending. The Means to Prosperity contains one of the first mentions of the multiplier effect. While it was addressed chiefly to the British Government, it also contained advice for other nations affected by the global recession. A copy was sent to the newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other world leaders. The work was taken seriously by both the American and British governments, and according to Robert Skidelsky, helped pave the way for the later acceptance of Keynesian ideas, though it had little immediate practical influence. In the 1933 London Economic Conference opinions remained too diverse for a unified course of action to be agreed upon.[46]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Keynesian-like policies were adopted by Sweden and Germany, but Sweden was seen as too small to command much attention, and Keynes was deliberately silent about the successful efforts of Germany as he was dismayed by its imperialist ambitions and its treatment of Jews.[46] Apart from Great Britain, Keynes's attention was primarily focused on the United States. In 1931, he received considerable support for his views on counter-cyclical public spending in Chicago, then America's foremost center for economic views alternative to the mainstream.[29][46] However, orthodox economic opinion remained generally hostile regarding fiscal intervention to mitigate the depression, until just before the outbreak of war.[29] In late 1933 Keynes was persuaded by Felix Frankfurter to address President Roosevelt directly, which he did by letters and face-to-face in 1934, after which the two men spoke highly of each other.[46] However, according to Skidelsky, the consensus is that Keynes's efforts began to have a more than marginal influence on US economic policy only after 1939.[46]

Keynes's magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money was published in 1936.[10] It was researched and indexed by one of Keynes's favourite students, and later economist, David Bensusan-Butt.[47] The work served as a theoretical justification for the interventionist policies Keynes favoured for tackling a recession. Although Keynes stated in his preface that his General Theory was only secondarily concerned with the "applications of this theory to practice," the circumstances of its publication were such that his suggestions shaped the course of the 1930s.[48] In addition, Keynes introduced the world to a new interpretation of taxation: since the legal tender is now defined by the state, inflation becomes "taxation by currency depreciation". This hidden tax meant a) that the standard of value should be governed by deliberate decision; and (b) that it was possible to maintain a middle course between deflation and inflation.[49] This novel interpretation was inspired by the desperate search for control over the economy which permeated the academic world after the Depression. The General Theory challenged the earlier neoclassical economic paradigm, which had held that provided it was unfettered by government interference, the market would naturally establish full employment equilibrium. In doing so Keynes was partly setting himself against his former teachers Marshall and Pigou. Keynes believed the classical theory was a "special case" that applied only to the particular conditions present in the 19th century, his theory being the general one. Classical economists had believed in Say's law, which, simply put, states that "supply creates its demand", and that in a free-market workers would always be willing to lower their wages to a level where employers could profitably offer them jobs.[50]

An innovation from Keynes was the concept of price stickiness – the recognition that in reality workers often refuse to lower their wage demands even in cases where a classical economist might argue that it is rational for them to do so. Due in part to price stickiness, it was established that the interaction of "aggregate demand" and "aggregate supply" may lead to stable unemployment equilibria – and in those cases, it is on the state, not the market, that economies must depend for their salvation. In contrast, Keynes argued that demand is what creates supply and not the other way around. He questioned Say's Law by asking what would happen if the money that is being given to individuals is not finding its way back into the economy and is saved instead. He suggested the result would be a recession. To tackle the fear of a recession Say's Law suggests government intervention. This government intervention can be used to prevent any further increase in savings in the form of a decreased interest rate. Decreasing the interest rate will encourage people to start spending and investing again, or so it is stated by Say's Law. The reason behind this is that when there is little investing, savings start to accumulate and reach a stopping point in the flow of money. During the normal economic activity, it would be justified to have savings because they can be given out as loans but in this case, there is little demand for them, so they are doing no good for the economy. The supply of savings then exceeds the demand for loans and the result is lower prices or lower interest rates. Thus, the idea is that the money that was once saved is now re-invested or spent, assuming lower interest rates appeal to consumers. To Keynes, however, this was not always the case, and it couldn't be assumed that lower interest rates would automatically encourage investment and spending again since there is no proven link between the two.[50]

The General Theory argues that demand, not supply, is the key variable governing the overall level of economic activity. Aggregate demand, which equals total un-hoarded income in a society, is defined by the sum of consumption and investment. In a state of unemployment and unused production capacity, one can enhance employment and total income only by first increasing expenditures for either consumption or investment. Without government intervention to increase expenditure, an economy can remain trapped in a low-employment equilibrium. The demonstration of this possibility has been described as the revolutionary formal achievement of the work.[51] The book advocated activist economic policy by government to stimulate demand in times of high unemployment, for example by spending on public works. "Let us be up and doing, using our idle resources to increase our wealth," he wrote in 1928. "With men and plants unemployed, it is ridiculous to say that we cannot afford these new developments. It is precisely with these plants and these men that we shall afford them."[45]

The General Theory is often viewed as the foundation of modern macroeconomics. Few senior American economists agreed with Keynes through most of the 1930s.[52] Yet his ideas were soon to achieve widespread acceptance, with eminent American professors such as Alvin Hansen agreeing with the General Theory before the outbreak of World War II.[53][54][55]

Keynes himself had only limited participation in the theoretical debates that followed the publication of the General Theory as he suffered a heart attack in 1937, requiring him to take long periods of rest. Among others, Hyman Minsky and Post-Keynesian economists have argued that as a result, Keynes's ideas were diluted by those keen to compromise with classical economists or to render his concepts with mathematical models like the IS–LM model (which, they argue, distort Keynes's ideas).[29][55] Keynes began to recover in 1939, but for the rest of his life his professional energies were directed largely towards the practical side of economics: the problems of ensuring optimum allocation of resources for the war efforts, post-war negotiations with America, and the new international financial order that was presented at the Bretton Woods Conference.

In the General Theory and later, Keynes responded to the socialists who argued, especially during the Great Depression of the 1930s, that capitalism caused war. He argued that if capitalism were managed domestically and internationally (with coordinated international Keynesian policies, an international monetary system that did not pit the interests of countries against one another, and a high degree of freedom of trade), then this system of managed capitalism could promote peace rather than conflict between countries. His plans during World War II for post-war international economic institutions and policies (which contributed to the creation at Bretton Woods of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and later to the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and eventually the World Trade Organization) were aimed to give effect to this vision.[56]

Although Keynes has been widely criticised – especially by members of the Chicago school of economics – for advocating irresponsible government spending financed by borrowing, in fact he was a firm believer in balanced budgets and regarded the proposals for programmes of public works during the Great Depression as an exceptional measure to meet the needs of exceptional circumstances.[57]

Second World War

[edit]

During the Second World War, Keynes argued in How to Pay for the War, published in 1940, that the war effort should be largely financed by higher taxation and especially by compulsory saving (essentially workers lending money to the government), rather than deficit spending, to avoid inflation. Compulsory saving would act to dampen domestic demand, assist in channelling additional output towards the war efforts, would be fairer than punitive taxation and would have the advantage of helping to avoid a post-war slump by boosting demand once workers were allowed to withdraw their savings. In September 1941 he was proposed to fill a vacancy in the Court of Directors of the Bank of England, and subsequently carried out a full term from the following April.[58] In June 1942, Keynes was rewarded for his service with a hereditary peerage in the King's Birthday Honours.[59] On 7 July his title was gazetted as "Baron Keynes, of Tilton, in the County of Sussex" and he took his seat in the House of Lords on the Liberal Party benches.[60]

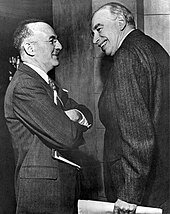

As the Allied victory began to look certain, Keynes was heavily involved, as leader of the British delegation and chairman of the World Bank commission, in the mid-1944 negotiations that established the Bretton Woods system. The Keynes plan, concerning an international clearing-union, argued for a radical system for the management of currencies. He proposed the creation of a common world unit of currency, the bancor and new global institutions – a world central bank and the International Clearing Union. Keynes envisaged these institutions as managing an international trade and payments system with strong incentives for countries to avoid substantial trade deficits or surpluses.[61] The USA's greater negotiating strength, however, meant that the outcomes accorded more closely to the more conservative plans of Harry Dexter White. According to US economist J. Bradford DeLong, on almost every point where he was overruled by the Americans, Keynes was later proven correct by events.[62]

The two new institutions, later known as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), were founded as a compromise that primarily reflected the American vision. There would be no incentives for states to avoid a large trade surplus; instead, the burden for correcting a trade imbalance would continue to fall only on the deficit countries, which Keynes had argued were least able to address the problem without inflicting economic hardship on their populations. Yet, Keynes was still pleased when accepting the final agreement, saying that if the institutions stayed true to their founding principles, "the brotherhood of man will have become more than a phrase."[63][64]

Postwar

[edit]After the war, Keynes continued to represent the United Kingdom in international negotiations despite his deteriorating health. He succeeded in obtaining preferential terms from the United States for new and outstanding debts to facilitate the rebuilding of the British economy.[65]

Just before his death in 1946, Keynes told Henry Clay, a professor of social economics and advisor to the Bank of England,[66] of his hopes that Adam Smith's "invisible hand" could help Britain out of the economic hole it was in: "I find myself more and more relying for a solution of our problems on the invisible hand which I tried to eject from economic thinking twenty years ago."[67]

Influence and legacy

[edit]

Keynesian ascendancy 1939–79

[edit]From the end of the Great Depression to the mid-1970s, Keynes provided the main inspiration for economic policymakers in Europe, America and much of the rest of the world.[55] While economists and policymakers had become increasingly won over to Keynes's way of thinking in the mid and late 1930s, it was only after the outbreak of World War II that governments started to borrow money for spending on a scale sufficient to eliminate unemployment. According to the economist John Kenneth Galbraith (then a US government official charged with controlling inflation), in the rebound of the economy from wartime spending, "one could not have had a better demonstration of the Keynesian ideas".[68]

The Keynesian Revolution was associated with the rise of modern liberalism in the West during the post-war period.[69] Keynesian ideas became so popular that some scholars point to Keynes as representing the ideals of modern liberalism, as Adam Smith represented the ideals of classical liberalism.[70] After the war, Winston Churchill attempted to check the rise of Keynesian policy-making in the United Kingdom and used rhetoric critical of the mixed economy in his 1945 election campaign. Despite his popularity as a war hero, Churchill suffered a landslide defeat to Clement Attlee, whose government's economic policy continued to be influenced by Keynes's ideas.[68]

Neo-Keynesian economics

[edit]

In the late 1930s and 1940s, economists (notably John Hicks, Franco Modigliani and Paul Samuelson) attempted to interpret and formalise Keynes's writings in terms of formal mathematical models. In what had become known as the neoclassical synthesis, they combined Keynesian analysis with neoclassical economics to produce neo-Keynesian economics, which came to dominate mainstream macroeconomic thought for the next 40 years.

By the 1950s, Keynesian policies were adopted by almost the entire developed world and similar measures for a mixed economy were used by many developing nations. By then, Keynes's views on the economy had become mainstream in the world's universities. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the developed and emerging free capitalist economies enjoyed exceptionally high growth and low unemployment.[71][72] Professor Gordon Fletcher has written that the 1950s and 1960s, when Keynes's influence was at its peak, appear in retrospect as a golden age of capitalism.[55]

In late 1965 Time magazine ran a cover article with a title comment from Milton Friedman (later echoed by US President Richard Nixon), "We are all Keynesians now". The article described the exceptionally favourable economic conditions then prevailing and reported that "Washington's economic managers scaled these heights by their adherence to Keynes's central theme: the modern capitalist economy does not automatically work at top efficiency, but can be raised to that level by the intervention and influence of the government." The article also states that Keynes was one of the three most important economists who ever lived, and that his General Theory was more influential than the magna opera of other famous economists, such as Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations.[73]

Multiplier

[edit]The concept of the multiplier was first developed by R. F. Kahn[74] in his article "The relation of home investment to unemployment"[75] in The Economic Journal of June 1931. The Kahn multiplier was the employment multiplier; Keynes took the idea from Kahn and formulated the investment multiplier.[76]

Keynesian economics out of favour 1979–2007

[edit]Keynesian economics were officially discarded by the British Government in 1979, but forces had begun to gather against Keynes's ideas over 30 years earlier. Friedrich Hayek had formed the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, with the explicit intention of nurturing intellectual currents to one day displace Keynesianism and other similar influences. Its members included the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises along with the then-young Milton Friedman. Initially, the society had little impact on the wider world – according to Hayek it was as if Keynes had been raised to sainthood after his death and that people refused to allow his work to be questioned.[77][78] Friedman, however, began to emerge as a formidable critic of Keynesian economics from the mid-1950s, and especially after his 1963 publication of A Monetary History of the United States.

On the practical side of economic life, "big government" had appeared to be firmly entrenched in the 1950s, but the balance began to shift towards the power of private interests in the 1960s. Keynes had written against the folly of allowing "decadent and selfish" speculators and financiers the kind of influence they had enjoyed after World War I. For two decades after World War II public opinion was strongly against private speculators, the disparaging label "Gnomes of Zurich" being typical of how they were described during this period. International speculation was severely restricted by the capital controls in place after Bretton Woods. According to the journalists Larry Elliott and Dan Atkinson, 1968 was the pivotal year when power shifted in favour of private agents such as currency speculators. As the key 1968 event Elliott and Atkinson picked out America's suspension of the conversion of the dollar into gold except on request of foreign governments, which they identified as the beginning of the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system.[79]

Criticisms of Keynes's ideas had begun to gain significant acceptance by the early 1970s, as they were then able to make a credible case that Keynesian models no longer reflected economic reality. Keynes himself included few formulas and no explicit mathematical models in his General Theory. For economists such as Hyman Minsky, Keynes's limited use of mathematics was partly the result of his scepticism about whether phenomena as inherently uncertain as economic activity could ever be adequately captured by mathematical models. Nevertheless, many models were developed by Keynesian economists, with a famous example being the Phillips curve which predicted an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. It implied that unemployment could be reduced by government stimulus with a calculable cost to inflation. In 1968, Milton Friedman published a paper arguing that the fixed relationship implied by the Philips curve did not exist.[80] Friedman suggested that sustained Keynesian policies could lead to both unemployment and inflation rising at once – a phenomenon that soon became known as stagflation. In the early 1970s stagflation appeared in both the US and Britain just as Friedman had predicted, with economic conditions deteriorating further after the 1973 oil crisis. Aided by the prestige gained from his successful forecast, Friedman led increasingly successful criticisms against the Keynesian consensus, convincing not only academics and politicians but also much of the general public with his radio and television broadcasts. The academic credibility of Keynesian economics was further undermined by additional criticism from other monetarists trained in the Chicago school of economics, by the Lucas critique and by criticisms from Hayek's Austrian School.[55] So successful were these criticisms that by 1980 Robert Lucas claimed economists would often take offence if described as Keynesians.[81]

Keynesian principles fared increasingly poorly on the practical side of economics – by 1979 they had been displaced by monetarism as the primary influence on Anglo-American economic policy.[55] However, many officials on both sides of the Atlantic retained a preference for Keynes, and in 1984 the Federal Reserve officially discarded monetarism, after which Keynesian principles made a partial comeback as an influence on policy-making.[82] Not all academics accepted the criticism against Keynes – Minsky has argued that Keynesian economics had been debased by excessive mixing with neoclassical ideas from the 1950s, and that it was unfortunate that this branch of economics had even continued to be called "Keynesian".[29] Writing in The American Prospect, Robert Kuttner argued it was not so much excessive Keynesian activism that caused the economic problems of the 1970s but the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of capital controls, which allowed capital flight from regulated economies into unregulated economies in a fashion similar to Gresham's law phenomenon (where weak currencies undermine strong ones).[83] Historian Peter Pugh has stated that a key cause of the economic problems afflicting America in the 1970s was the refusal to raise taxes to finance the Vietnam War, which was against Keynesian advice.[84]

A more typical response was to accept some elements of the criticisms while refining Keynesian economic theories to defend them against arguments that would invalidate the whole Keynesian framework – the resulting body of work largely composing New Keynesian economics. In 1992 Alan Blinder wrote about a "Keynesian Restoration", as work based on Keynes's ideas had to some extent become fashionable once again in academia, though in the mainstream it was highly synthesised with monetarism and other neoclassical thinking. In the world of policy making, free market influences broadly sympathetic to monetarism have remained very strong at government level – in powerful normative institutions like the World Bank, the IMF and US Treasury, and in prominent opinion-forming media such as the Financial Times and The Economist.[85]

Keynesian resurgence 2008–09

[edit]

The 2007–2008 financial crisis led to public skepticism about the free market consensus even from some on the economic right. In March 2008, Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, announced the death of the dream of global free-market capitalism.[87] In the same month macroeconomist James K. Galbraith used the 25th Annual Milton Friedman Distinguished Lecture to launch a sweeping attack against the consensus for monetarist economics and argued that Keynesian economics were far more relevant for tackling the emerging crises.[88] Economist Robert J. Shiller had begun advocating robust government intervention to tackle the financial crises, specifically citing Keynes.[89][90][91] Nobel laureate Paul Krugman also actively argued the case for vigorous Keynesian intervention in the economy in his columns for The New York Times.[92][93][94] Other prominent economic commentators who have argued for Keynesian government intervention to mitigate the 2007–2008 financial crisis included George Akerlof,[95] J. Bradford DeLong,[96] Robert Reich[97] and Joseph Stiglitz.[98] Newspapers and other media have also cited work relating to Keynes by Hyman Minsky,[29] Robert Skidelsky,[18] Donald Markwell[99] and Axel Leijonhufvud.[100]

A series of major bailouts were pursued during the 2007–2008 financial crisis, starting on 7 September 2008 with the announcement that the US Government was to nationalise the two government-sponsored enterprises which oversaw most of the US subprime mortgage market – Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In October, Alistair Darling, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, referred to Keynes as he announced plans for substantial fiscal stimulus to head off the worst effects of recession, in accordance with Keynesian economic thought.[101][102] Similar policies have been adopted by other governments worldwide.[103][104] This was in stark contrast to the action imposed on Indonesia during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, when it was forced by the IMF to close 16 banks at the same time, prompting a bank run.[105] Much of the post-crisis discussion reflected Keynes's advocacy of international coordination of fiscal or monetary stimulus, and of international economic institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, which many had argued should be reformed as a "new Bretton Woods", and should have been even before the crises broke out.[106] The IMF and United Nations economists advocated a coordinated international approach to fiscal stimulus.[107] Donald Markwell argued that in the absence of such an international approach, there would be a risk of worsening international relations and possibly even world war arising from economic factors similar to those present during the depression of the 1930s.[99]

By the end of December 2008, the Financial Times reported that "the sudden resurgence of Keynesian policy is a stunning reversal of the orthodoxy of the past several decades."[108] In December 2008, Paul Krugman released his book The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008, arguing that economic conditions similar to those that existed during the earlier part of the 20th century had returned, making Keynesian policy prescriptions more relevant than ever. In February 2009 Robert J. Shiller and George Akerlof published Animal Spirits, a book where they argue the current US stimulus package is too small as it does not take into account Keynes's insight on the importance of confidence and expectations in determining the future behaviour of businesspeople and other economic agents.

In the March 2009 speech entitled Reform the International Monetary System, Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People's Bank of China, came out in favour of Keynes's idea of a centrally managed global reserve currency. Zhou argued that it was unfortunate that part of the reason for the Bretton Woods system breaking down was the failure to adopt Keynes's bancor. Zhou proposed a gradual move towards increased use of IMF special drawing rights (SDRs).[109][110] Although Zhou's ideas had not been broadly accepted, leaders meeting in April at the 2009 G-20 London summit agreed to allow $250 billion of special drawing rights to be created by the IMF, to be distributed globally. Stimulus plans were credited for contributing to a better-than-expected economic outlook by both the OECD[111] and the IMF,[112][113] in reports published in June and July 2009. Both organisations warned global leaders that recovery was likely to be slow, so counter-recessionary measures ought not be rolled back too early.

While the need for stimulus measures was broadly accepted among policymakers, there had been much debate over how to fund the spending. Some leaders and institutions, such as Angela Merkel[114] and the European Central Bank,[115] expressed concern over the potential impact on inflation, national debt and the risk that a too-large stimulus will create an unsustainable recovery.

Among professional economists the revival of Keynesian economics has been even more divisive. Although many economists, such as George Akerlof, Paul Krugman, Robert Shiller and Joseph Stiglitz, supported Keynesian stimulus, others did not believe higher government spending would help the United States economy recover from the Great Recession. Some economists, such as Robert Lucas, questioned the theoretical basis for stimulus packages.[116] Others, like Robert Barro and Gary Becker, say that empirical evidence for beneficial effects from Keynesian stimulus does not exist.[117] However, there is a growing academic literature that shows that fiscal expansion helps an economy grow in the near term, and that certain types of fiscal stimulus are particularly effective.[118][119]

New Keynesian economics

[edit]New Keynesian economics developed in the 1990s and early 2000s as a response to the critique that macroeconomics lacked microeconomic foundations. New Keynesianism developed models to provide microfoundations for Keynesian economics. It incorporated parts of new classical macroeconomics to develop the new neoclassical synthesis, which forms the basis for mainstream macroeconomics today.[120][121][122][123]

Two main assumptions define the New Keynesian approach to macroeconomics. Like the New Classical approach, New Keynesian macroeconomic analysis usually assumes that households and firms have rational expectations. However, the two schools differ in that New Keynesian analysis usually assumes a variety of market failures. In particular, New Keynesians assume that there is imperfect competition[124] in price and wage setting to help explain why prices and wages can become "sticky", which means they do not adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.

Wage and price stickiness, and the other market failures present in New Keynesian models, imply that the economy may fail to attain full employment. Therefore, New Keynesians argue that macroeconomic stabilisation by the government (using fiscal policy) and the central bank (using monetary policy) can lead to a more efficient macroeconomic outcome than a laissez faire policy would.

Overall views

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Praise

[edit]On a personal level, Keynes's charm was such that he was generally well received wherever he went – even those who found themselves on the wrong side of his occasionally sharp tongue rarely bore a grudge.[125] Keynes's speech at the closing of the Bretton Woods negotiations was received with a lasting standing ovation, rare in international relations, as the delegates acknowledged the scale of his achievements made despite poor health.[26]

Austrian School economist Friedrich Hayek was Keynes's most prominent contemporary critic, with sharply opposing views on the economy.[51] Yet after Keynes's death, he wrote: "He was the one really great man I ever knew, and for whom I had unbounded admiration. The world will be a very much poorer place without him."[126] A colleague Nicholas Davenport recalled, "There were deep emotional forces about Maynard ... One could sense his humanity. There was nothing of the cold intellectual about him."[127]

Lionel Robbins, former head of the economics department at the London School of Economics, who engaged in many heated debates with Keynes in the 1930s, had this to say after observing Keynes in early negotiations with the Americans while drawing up plans for Bretton Woods:[51]

This went very well indeed. Keynes was in his most lucid and persuasive mood: and the effect was irresistible. At such moments, I often find myself thinking that Keynes must be one of the most remarkable men that have ever lived – the quick logic, the birdlike swoop of intuition, the vivid fancy, the wide vision, above all the incomparable sense of the fitness of words, all combine to make something several degrees beyond the limit of ordinary human achievement.

Douglas LePan, an official from the Canadian High Commission,[51] wrote:

I am spellbound. This is the most beautiful creature I have ever listened to. Does he belong to our species? Or is he from some other order? There is something mythic and fabulous about him. I sense in him something massive and sphinx like, and yet also a hint of wings.

Bertrand Russell named Keynes one of the most intelligent people he had ever known,[128] commenting:[129]

Keynes's intellect was the sharpest and clearest that I have ever known. When I argued with him, I felt that I took my life in my hands, and I seldom emerged without feeling something of a fool.

Keynes's obituary in The Times included the comment: "There is the man himself – radiant, brilliant, effervescent, gay, full of impish jokes ... He was a humane man genuinely devoted to the cause of the common good."[53]

Critiques

[edit]As a man of the centre described by some as having the greatest impact of any 20th-century economist,[44] Keynes attracted considerable criticism from both sides of the political spectrum. In the 1920s, Keynes was seen as anti-establishment and was mainly attacked from the right. In the "red 1930s", many young economists favoured Marxist views, even in Cambridge,[29] and while Keynes was engaging principally with the right to try to persuade them of the merits of more progressive policy, the most vociferous criticism against him came from the left, who saw him as a supporter of capitalism. From the 1950s and onwards, most of the attacks against Keynes have again been from the right.

In 1931, Friedrich Hayek extensively critiqued Keynes's 1930 Treatise on Money.[130] After reading Hayek's The Road to Serfdom, Keynes wrote to Hayek: "Morally and philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it."[131] He concluded the letter with the recommendation:

What we need therefore, in my opinion, is not a change in our economic programmes, which would only lead in practice to disillusion with the results of your philosophy; but perhaps even the contrary, namely, an enlargement of them. Your greatest danger is the probable practical failure of the application of your philosophy in the United States.

On the pressing issue of the time, whether deficit spending could lift a country from depression, Keynes replied to Hayek's criticism[132] in the following way:

I should... conclude rather differently. I should say that what we want is not no planning, or even less planning, indeed I should say we almost certainly want more. But the planning should take place in a community in which as many people as possible, both leaders and followers wholly share your moral position. Moderate planning will be safe enough if those carrying it out are rightly oriented in their minds and hearts to the moral issue.

Asked why Keynes expressed "moral and philosophical" agreement with Hayek's Road to Serfdom, Hayek stated:[133]

Because he believed that he was fundamentally still a classical English liberal and wasn't quite aware of how far he had moved away from it. His basic ideas were still those of individual freedom. He did not think systematically enough to see the conflicts. He was, in a sense, corrupted by political necessity.

According to some observers,[who?] Hayek felt that the post-World War II "Keynesian orthodoxy" gave too much power to the state, and that such policies would lead toward socialism.[134]

While Milton Friedman described The General Theory as "a great book", he argues that its implicit separation of nominal from real magnitudes is neither possible nor desirable. Macroeconomic policy, Friedman argues, can reliably influence only the nominal.[135] He and other monetarists have consequently argued that Keynesian economics can result in stagflation, the combination of low growth and high inflation that developed economies suffered in the early 1970s. More to Friedman's taste was the Tract on Monetary Reform (1923), which he regarded as Keynes's best work because of its focus on maintaining domestic price stability.[135]

Joseph Schumpeter was an economist of the same age as Keynes and one of his main rivals. He was among the first reviewers to argue that Keynes's General Theory was not a general theory, but a special case.[136] He said the work expressed "the attitude of a decaying civilisation". After Keynes's death Schumpeter wrote a brief biographical piece Keynes the Economist – on a personal level he was very positive about Keynes as a man, praising his pleasant nature, courtesy and kindness. He assessed some of Keynes's biographical and editorial work as among the best he'd ever seen. Yet Schumpeter remained critical of Keynes's economics, linking Keynes's childlessness to what Schumpeter saw as an essentially short-term view. He considered Keynes to have a kind of unconscious patriotism that caused him to fail to understand the problems of other nations. For Schumpeter, "Practical Keynesianism is a seedling which cannot be transplanted into foreign soil: it dies there and becomes poisonous as it dies."[137] He "admired and envied Keynes, but when Keynes died in 1946, Schumpeter's obituary gave Keynes this same off-key, perfunctory treatment he would later give Adam Smith in the History of Economic Analysis, the "discredit of not adding a single innovation to the techniques of economic analysis."[138]

Ludwig von Mises, an Austrian economist, describes a Keynesian system as believing it can solve most problems with "more money and credit" which leads to a system of "inflationism" in which "prices (of goods) rise higher and higher."[139] Murray Rothbard wrote that Keynesian-style governmental regulation of money and credit created a "dismal monetary and banking situation," since it allows for the central bankers that have the exclusive ability to print money to be "unchecked and out of control."[140] Rothbard went on to say in an interview that, "There is one good thing about (Karl) Marx: he was not a Keynesian."[141]

President Harry S. Truman was sceptical of Keynesian theorising. He told Leon Keyserling, a Keynesian economist who chaired Truman's Council of Economic Advisers: "Nobody can ever convince me that government can spend a dollar that it's not got."[45]

Views on race

[edit]Some critics have sought to show that Keynes had sympathies towards Nazism, and a number of writers have described him as antisemitic. Keynes's private letters contain portraits and descriptions, some of which can be characterised as antisemitic, while others as philosemitic.[142][143]

Scholars have suggested that these reflect clichés current at the time that he accepted uncritically, rather than any racism.[144] On several occasions Keynes used his influence to help his Jewish friends, most notably when he successfully lobbied for Ludwig Wittgenstein to be allowed residency in the United Kingdom, explicitly to rescue him from being deported to Nazi-occupied Austria. Keynes was a supporter of Zionism, serving on committees supporting the cause.[144]

Allegations that he was racist or had totalitarian beliefs have been rejected by Robert Skidelsky and other biographers.[26] Professor Gordon Fletcher wrote that "the suggestion of a link between Keynes and any support of totalitarianism cannot be sustained".[55] Once the aggressive tendencies of the Nazis towards Jews and other minorities had become apparent, Keynes made clear his loathing of Nazism. As a lifelong pacifist he had initially favoured peaceful containment of Nazi Germany, yet he began to advocate a forceful resolution while many conservatives were still arguing for appeasement. After the war started, he roundly criticised the Left for losing their nerve to confront Adolf Hitler, saying:

The intelligentsia of the Left were the loudest in demanding that the Nazi aggression should be resisted at all costs. When it comes to a showdown, scarce four weeks have passed before they remember that they are pacifists and write defeatist letters to your columns, leaving the defence of freedom and civilisation to Colonel Blimp and the Old School Tie, for whom Three Cheers.[51]

Views on inflation

[edit]Keynes has been characterised as being indifferent or even positive about mild inflation.[145] He had expressed a preference for inflation over deflation, saying that if one has to choose between the two evils, it is "better to disappoint the rentier" than to inflict pain on working-class families.[146] Keynes was also aware of the dangers of inflation.[55][page range too broad] In The Economic Consequences of the Peace, he wrote:

Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the Capitalist System was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.[145]

Views on free trade and protectionism

[edit]Turning point of the Great Depression

[edit]At the beginning of his career, Keynes was an economist close to Alfred Marshall, deeply convinced of the benefits of free trade. From the crisis of 1929 onwards, noting the commitment of the British authorities to defend the gold parity of the pound sterling and the rigidity of nominal wages, he gradually adhered to protectionist measures.[147]

On 5 November 1929, when heard by the Macmillan Committee to bring the British economy out of the crisis, Keynes indicated that the introduction of tariffs on imports would help to rebalance the trade balance. The committee's report states in a section entitled "import control and export aid", that in an economy where there is not full employment, the introduction of tariffs can improve production and employment. Thus, the reduction of the trade deficit favours the country's growth.[147]

In January 1930, in the Economic Advisory Council, Keynes proposed the introduction of a system of protection to reduce imports. In the autumn of 1930, he proposed a uniform tariff of 10% on all imports and subsidies of the same rate for all exports.[147] In the Treatise on Money, published in the autumn of 1930, he took up the idea of tariffs or other trade restrictions with the aim of reducing the volume of imports and rebalancing the balance of trade.[147]

On 7 March 1931, in the New Statesman and Nation, he wrote an article entitled Proposal for a Tariff Revenue. He pointed out that the reduction in wages led to a reduction in national demand which constrained markets. Instead, he proposed the idea of an expansionary policy combined with a tariff system to neutralise the effects on the balance of trade. The application of customs tariffs seemed to him "unavoidable, whoever the Chancellor of the Exchequer might be". Thus, for Keynes, an economic recovery policy is only fully effective if the trade deficit is eliminated. He proposed a 15% tax on manufactured and semi-manufactured goods and 5% on certain foodstuffs and raw materials, with others needed for exports exempted (wool, cotton).[147]

In 1932, in an article entitled The Pro- and Anti-Tariffs, published in The Listener, he envisaged the protection of farmers and certain sectors such as the automobile and iron and steel industries, considering them indispensable to Britain.[147]

Critique of the theory of comparative advantage

[edit]In the post-crisis situation of 1929, Keynes judged the assumptions of the free trade model unrealistic. He criticised, for example, the neoclassical assumption of wage adjustment.[147][148]

As early as 1930, in a note to the Economic Advisory Council, he doubted the intensity of the gain from specialisation in the case of manufactured goods. While participating in the MacMillan Committee, he admitted that he no longer "believed in a very high degree of national specialisation" and refused to "abandon any industry which is unable, for the moment, to survive". He also criticised the static dimension of the theory of comparative advantage, which, in his view, by fixing comparative advantages definitively, led in practice to a waste of national resources.[147][148]

In the Daily Mail of 13 March 1931, he called the assumption of perfect sectoral labour mobility "nonsense" since it states that a person made unemployed contributes to a reduction in the wage rate until he finds a job. But for Keynes, this change of job may involve costs (job search, training) and is not always possible. Generally speaking, for Keynes, the assumptions of full employment and automatic return to equilibrium discredit the theory of comparative advantage.[147][148]

In July 1933, he published an article in the New Statesman and Nation entitled National Self-Sufficiency, in which he criticised the argument of the specialisation of economies, which is the basis of free trade. He thus proposed the search for a certain degree of self-sufficiency. Instead of the specialisation of economies advocated by the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage, he prefers the maintenance of a diversity of activities for nations.[148] In it he refutes the principle of peacemaking trade. His vision of trade became that of a system where foreign capitalists compete for new markets. He defends the idea of producing on national soil when possible and reasonable and expresses sympathy for the advocates of protectionism.[149] He notes in National Self-Sufficiency:[149][147]

A considerable degree of international specialization is necessary in a rational world in all cases where it is dictated by wide differences of climate, natural resources, native aptitudes, level of culture and density of population. But over an increasingly wide range of industrial products, and perhaps of agricultural products also, I have become doubtful whether the economic loss of national self-sufficiency is great enough to outweigh the other advantages of gradually bringing the product and the consumer within the ambit of the same national, economic, and financial organization. Experience accumulates to prove that most modern processes of mass production can be performed in most countries and climates with almost equal efficiency.

He also writes in National Self-Sufficiency:[147]

I sympathize, therefore, with those who would minimize, rather than with those who would maximize, economic entanglement among nations. Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel – these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national.

Later, Keynes had a written correspondence with James Meade centred on the issue of import restrictions. Keynes and Meade discussed the best choice between quota and tariff. In March 1944 Keynes began a discussion with Marcus Fleming after the latter had written an article entitled Quotas versus depreciation. On this occasion, we see that he has definitely taken a protectionist stance after the Great Depression. He considered that quotas could be more effective than currency depreciation in dealing with external imbalances. Thus, for Keynes, currency depreciation was no longer sufficient and protectionist measures became necessary to avoid trade deficits. To avoid the return of crises due to a self-regulating economic system, it seemed essential to him to regulate trade and stop free trade (deregulation of foreign trade).[147]

He points out that countries that import more than they export weaken their economies. When the trade deficit increases, unemployment rises and gross domestic product (GDP) slows down. Furthermore, surplus countries exert a "negative externality" on their trading partners. They get richer at the expense of others and destroy the output of their trading partners. John Maynard Keynes believed that the products of surplus countries should be taxed to avoid trade imbalances.[150]

Views on trade imbalances

[edit]Keynes was the principal author of a proposal – the so-called Keynes Plan – for an International Clearing Union. The two governing principles of the plan were that the problem of settling outstanding balances should be solved by "creating" additional "international money", and that debtor and creditor should be treated almost alike as disturbers of equilibrium. In the event, though, the plans were rejected, in part because "American opinion was naturally reluctant to accept the principle of equality of treatment so novel in debtor-creditor relationships".[151]

The new system is not founded on free-trade (liberalisation[152] of foreign trade[153]) but rather on the regulation of international trade, to eliminate trade imbalances: the nations with a surplus would have an incentive to reduce it, and in doing so they would automatically clear other nations deficits.[154] He proposed a global bank that would issue its currency – the bancor – which was exchangeable with national currencies at fixed rates of exchange and would become the unit of account between nations, which means it would be used to measure a country's trade deficit or trade surplus. Every country would have an overdraft facility in its bancor account at the International Clearing Union. He pointed out that surpluses lead to weak global aggregate demand – countries running surpluses exert a "negative externality" on trading partners, and pose, far more than those in deficit, a threat to global prosperity.[155]

In his 1933 Yale Review article "National Self-Sufficiency",[156][157] he already highlighted the problems created by free trade. His view, supported by many economists and commentators at the time, was that creditor nations may be just as responsible as debtor nations for disequilibrium in exchanges and that both should be under an obligation to bring trade back into a state of balance. Failure for them to do so could have serious consequences. In the words of Geoffrey Crowther, then editor of The Economist, "If the economic relationships between nations are not, by one means or another, brought fairly close to balance, then there is no set of financial arrangements that can rescue the world from the impoverishing results of chaos."[158]

These ideas were informed by events prior to the Great Depression when – in the opinion of Keynes and others – international lending, primarily by the US, exceeded the capacity of sound investment and so got diverted into non-productive and speculative uses, which in turn invited default and a sudden stop to the process of lending.[159]

Influenced by Keynes, economics texts in the immediate post-war period put a significant emphasis on balance in trade. For example, the second edition of the popular introductory textbook, An Outline of Money,[160] devoted the last three of its ten chapters to questions of foreign exchange management and in particular the "problem of balance". However, in more recent years, since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, with the increasing influence of monetarist schools of thought in the 1980s, and particularly in the face of large sustained trade imbalances, these concerns – and particularly concerns about the destabilising effects of large trade surpluses – have largely disappeared from mainstream economics discourse[161][page needed] and Keynes's insights have slipped from view.[162][page needed] They received some attention again after the 2007–2008 financial crisis.[163]

Personal life

[edit]

Relationships

[edit]Keynes's early romantic and sexual relationships were exclusively with men.[164] Keynes had been in relationships while at Eton and Cambridge; significant among these early partners were Dilly Knox and Daniel Macmillan.[20][165] Keynes was open about his affairs, and from 1901 to 1915 kept separate diaries in which he tabulated his many sexual encounters.[166][167] Keynes's relationship and later close friendship with Macmillan was to be fortunate, as Macmillan's company first published his tract Economic Consequences of the Peace.[168]

Attitudes in the Bloomsbury Group, in which Keynes was avidly involved, were relaxed about homosexuality. Keynes, together with writer Lytton Strachey, had reshaped the Victorian attitudes of the Cambridge Apostles: "since [their] time, homosexual relations among the members were for a time common", wrote Bertrand Russell.[169] The artist Duncan Grant has been described as "the supreme male love of Keynes's life", and their sexual relationship lasted from 1908 to 1915.[170] Keynes was also involved with Lytton Strachey,[164] though they were, for the most part, love rivals rather than lovers. Keynes had won the affections of Arthur Hobhouse,[171] and as with Grant, fell out with a jealous Strachey over it.[172] Strachey had previously found himself put off by Keynes, not least because of his manner of "treat[ing] his love affairs statistically".[173]

Political opponents have used Keynes's sexuality to attack his academic work.[174] One line of attack held that he was uninterested in the long-term ramifications of his theories because he had no children.[174] Donald Kagan, in On the Origins of War, quotes Sally Marks and Stephen A. Schuker to suggest that "[Keynes's] passion for Carl Melchior" distorted his position in favor of Germany.[175]

Keynes's friends in the Bloomsbury Group were initially surprised when, in his later years, he began pursuing affairs with women,[176] demonstrating himself to be bisexual.[177] Ray Costelloe (who later married Oliver Strachey) was an early heterosexual interest of Keynes.[178] In 1906, Keynes had written of this infatuation that, "I seem to have fallen in love with Ray a little bit, but as she isn't male I haven't [been] able to think of any suitable steps to take."[179]

Marriage

[edit]

In 1921, Keynes wrote that he had fallen "very much in love" with Lydia Lopokova, a well-known Russian ballerina and one of the stars of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.[180] In the early years of his courtship, he maintained an affair with a younger man, Sebastian Sprott, in tandem with Lopokova, but eventually chose Lopokova exclusively.[181][182] They were married in 1925, with Keynes's former lover Duncan Grant as best man.[128][164] "What a marriage of beauty and brains, the fair Lopokova and John Maynard Keynes" was said at the time. Keynes later commented to Strachey that beauty and intelligence were rarely found in the same person, and that only in Duncan Grant had he found the combination.[183] The union was happy, with biographer Peter Clarke writing that the marriage gave Keynes "a new focus, a new emotional stability and a sheer delight of which he never wearied".[32][184] The couple hoped to have children but this did not happen.[32]

Among Keynes's Bloomsbury friends, Lopokova was, at least initially, subjected to criticism for her manners, mode of conversation and supposedly humble social origins – the last of the ostensible causes being particularly noted in the letters of Vanessa and Clive Bell, and Virginia Woolf.[185][186] In her novel Mrs Dalloway (1925), Woolf bases the character of Rezia Warren Smith on Lopokova.[187] E. M. Forster later wrote in contrition about "Lydia Keynes, every whose word should be recorded";[188] "How we all used to underestimate her".[185]

Keynes had no children, and his wife outlived him by 35 years, dying in 1981.

Support for the arts

[edit]Keynes thought that the pursuit of money for its own sake was a pathological condition, and that the proper aim of work is to provide leisure. He wanted shorter working hours and longer holidays for all.[57]

Keynes was interested in literature in general and drama in particular and supported the Cambridge Arts Theatre financially, which allowed the institution to become one of the major British stages outside London.[128]

Keynes's interest in classical opera and dance led him to support the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden and the Ballet Company at Sadler's Wells. During the war, as a member of CEMA (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts), Keynes helped secure government funds to maintain both companies while their venues were shut. Following the war, Keynes was instrumental in establishing the Arts Council of Great Britain and was its founding chairman in 1946. From the start, the two organisations that received the largest grants from the new body were the Royal Opera House and Sadler's Wells.

Keynes built up a substantial collection of fine art, including works by Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Amedeo Modigliani, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso and Georges Seurat (some of which can now be seen at the Fitzwilliam Museum).[128] He enjoyed collecting books; he collected and protected many of Isaac Newton's papers. In part on the basis of these papers, Keynes wrote of Newton as "the last of the magicians."[190]

Philosophical and spiritual views