Doomsday Clock

| Doomsday Clock | |

|---|---|

The Doomsday Clock pictured at its setting of "90 seconds to midnight", last changed in January 2023 | |

| Frequency | Annually |

| Inaugurated | June 1947 |

| Most recent | January 23, 2024 |

| Website | thebulletin |

The Doomsday Clock is a symbol that represents the likelihood of a human-made global catastrophe, in the opinion of the members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.[1] Maintained since 1947, the Clock is a metaphor, not a prediction, for threats to humanity from unchecked scientific and technological advances. That is, the time on the Clock is not to be interpreted as actual time. A hypothetical global catastrophe is represented by midnight on the Clock, with the Bulletin's opinion on how close the world is to one represented by a certain number of minutes or seconds to midnight, which is then assessed in January of each year. The main factors influencing the Clock are nuclear warfare, climate change, and artificial intelligence.[2][3] The Bulletin's Science and Security Board monitors new developments in the life sciences and technology that could inflict irrevocable harm to humanity.[4]

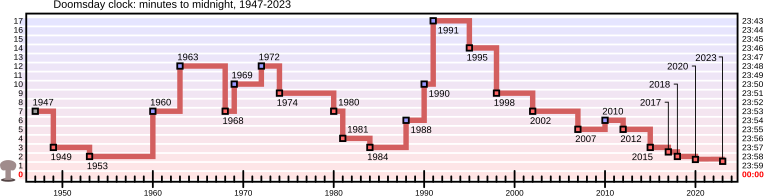

The Clock's original setting in 1947 was 7 minutes to midnight. It has since been set backward 8 times and forward 17 times. The farthest time from midnight was 17 minutes in 1991, and the nearest is 90 seconds, set in January 2023.

The Clock was moved to 150 seconds (2 minutes, 30 seconds) in 2017, then forward to 2 minutes to midnight in January 2018, and left unchanged in 2019.[5] In January 2020, it was moved forward to 100 seconds (1 minute, 40 seconds) before midnight.[6] In January 2023, the Clock was moved forward to 90 seconds (1 minute, 30 seconds) before midnight and remained unchanged in January 2024.[7][8]

History

[edit]

The Doomsday Clock's origin can be traced to the international group of researchers called the Chicago Atomic Scientists, who had participated in the Manhattan Project.[9] After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they began publishing a mimeographed newsletter and then the magazine, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which, since its inception, has depicted the Clock on every cover. The Clock was first represented in 1947, when the Bulletin co-founder Hyman Goldsmith asked artist Martyl Langsdorf (wife of Manhattan Project research associate and Szilárd petition signatory Alexander Langsdorf, Jr.) to design a cover for the magazine's June 1947 issue. As Eugene Rabinowitch, another co-founder of the Bulletin, explained later:

The Bulletin's Clock is not a gauge to register the ups and downs of the international power struggle; it is intended to reflect basic changes in the level of continuous danger in which mankind lives in the nuclear age...[10]

Langsdorf chose a clock to reflect the urgency of the problem: like a countdown, the Clock suggests that destruction will naturally occur unless someone takes action to stop it.[11]

In January 2007, designer Michael Bierut, who was on the Bulletin's Governing Board, redesigned the Doomsday Clock to give it a more modern feel. In 2009, the Bulletin ceased its print edition and became one of the first print publications in the U.S. to become entirely digital; the Clock is now found as part of the logo on the Bulletin's website. Information about the Doomsday Clock Symposium,[12] a timeline of the Clock's settings,[13] and multimedia shows about the Clock's history and culture[14] can also be found on the Bulletin's website.

The 5th Doomsday Clock Symposium[12] was held on November 14, 2013, in Washington, D.C.; it was a day-long event that was open to the public and featured panelists discussing various issues on the topic "Communicating Catastrophe". There was also an evening event at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in conjunction with the Hirshhorn's current exhibit, "Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950".[15] The panel discussions, held at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, were streamed live from the Bulletin's website and can still be viewed there.[16] Reflecting international events dangerous to humankind, the Clock has been adjusted 25 times since its inception in 1947, when it was set to "seven minutes to midnight".[17]

The Doomsday Clock has become a universally recognized metaphor according to The Two-Way, an NPR blog.[18] According to the Bulletin, the Clock attracts more daily visitors to the Bulletin's site than any other feature.[19]

Basis for settings

[edit]"Midnight" has a deeper meaning besides the constant threat of war. There are various elements taken into consideration when the scientists from the Bulletin decide what Midnight and "global catastrophe" really mean in a particular year. They might include "politics, energy, weapons, diplomacy, and climate science";[20] potential sources of threat include nuclear threats, climate change, bioterrorism, and artificial intelligence.[21] Members of the board judge Midnight by discussing how close they think humanity is to the end of civilization. In 1947, at the beginning of the Cold War, the Clock was started at seven minutes to midnight.[13]

Fluctuations and threats

[edit]Before January 2020, the two tied-for-lowest points for the Doomsday Clock were in 1953 (when the Clock was set to two minutes until midnight, after the U.S. and the Soviet Union began testing hydrogen bombs) and in 2018, following the failure of world leaders to address tensions relating to nuclear weapons and climate change issues. In other years, the Clock's time has fluctuated from 17 minutes in 1991 to 2 minutes 30 seconds in 2017.[13][22] Discussing the change to 2+1/2 minutes in 2017, the first use of a fraction in the Clock's history, Lawrence Krauss, one of the scientists from the Bulletin, warned that political leaders must make decisions based on facts, and those facts "must be taken into account if the future of humanity is to be preserved".[20] In an announcement from the Bulletin about the status of the Clock, they went as far to call for action from "wise" public officials and "wise" citizens to make an attempt to steer human life away from catastrophe while humans still can.[13]

On January 24, 2018, scientists moved the clock to two minutes to midnight, based on threats greatest in the nuclear realm. The scientists said, of recent moves by North Korea under Kim Jong-un and the administration of Donald Trump in the U.S.: "Hyperbolic rhetoric and provocative actions by both sides have increased the possibility of nuclear war by accident or miscalculation".[22]

The clock was left unchanged in 2019 due to the twin threats of nuclear weapons and climate change, and the problem of those threats being "exacerbated this past year by the increased use of information warfare to undermine democracy around the world, amplifying risk from these and other threats and putting the future of civilization in extraordinary danger".[5]

On January 23, 2020, the Clock was moved to 100 seconds (1 minute, 40 seconds) before midnight. The Bulletin's executive chairman, Jerry Brown, said "the dangerous rivalry and hostility among the superpowers increases the likelihood of nuclear blunder... Climate change just compounds the crisis".[6] The "100 seconds to midnight" setting remained unchanged in 2021 and 2022.

On January 24, 2023, the Clock was moved to 90 seconds (1 minute, 30 seconds) before midnight, the closest it has ever been set to midnight since its inception in 1947. This adjustment was largely attributed to the risk of nuclear escalation that arose from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Other reasons cited included climate change, biological threats such as COVID-19, and risks associated with disinformation and disruptive technologies.[7]

Criticism

[edit]Anders Sandberg of the Future of Humanity Institute has stated that the "grab bag of threats" currently mixed together by the Clock can induce paralysis. People may be more likely to succeed at smaller, incremental challenges; for example, taking steps to prevent the accidental detonation of nuclear weapons was a small but significant step towards avoiding nuclear war.[23][24] Alex Barasch in Slate argued that "putting humanity on a permanent, blanket high-alert isn't helpful when it comes to policy or science" and criticized the Bulletin for neither explaining nor attempting to quantify their methodology.[19]

Cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker harshly criticized the Doomsday Clock as a political stunt, pointing to the words of its founder that its purpose was "to preserve civilization by scaring men into rationality". He stated that it is inconsistent and not based on any objective indicators of security, using as an example its being farther from midnight in 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis than in the "far calmer 2007". He argued it was another example of humanity's tendency toward historical pessimism, and compared it to other predictions of self-destruction that went unfulfilled.[25]

Conservative media outlets have often criticized the Bulletin and the Doomsday Clock. Keith Payne writes in the National Review that the Clock overestimates the effects of "developments in the areas of nuclear testing and formal arms control".[26] Tristin Hopper in the National Post acknowledges that "there are plenty of things to worry about regarding climate change", but states that climate change is not in the same league as total nuclear destruction.[27] In addition, some critics accuse the Bulletin of pushing a political agenda.[23][27][28][29]

Timeline

[edit]

| Year | Minutes to midnight | Time (24-h) | Change (minutes) | Reason | Clock |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | 7 | 23:53 | 0 | The initial setting of the Doomsday Clock. |

|

| 1949 | 3 | 23:57 | −4 | The Soviet Union tests its first atomic bomb, the RDS-1, officially starting the nuclear arms race. |

|

| 1953 | 2 | 23:58 | −1 | The United States tests its first thermonuclear device in November 1952 as part of Operation Ivy, before the Soviet Union follows suit with the Joe 4 test in August. This remained the clock's closest approach to midnight (tied in 2018) until 2020. |

|

| 1960 | 7 | 23:53 | +5 | In response to a perception of increased scientific cooperation and public understanding of the dangers of nuclear weapons (as well as political actions taken to avoid "massive retaliation"), the United States and Soviet Union cooperate and avoid direct confrontation in regional conflicts such as the 1956 Suez Crisis, the 1958 Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, and the 1958 Lebanon crisis. Scientists from various countries help establish the International Geophysical Year, a series of coordinated, worldwide scientific observations between nations allied with both the United States and the Soviet Union, and the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, which allow Soviet and American scientists to interact. |

|

| 1963 | 12 | 23:48 | +5 | The United States and the Soviet Union sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty, limiting atmospheric nuclear testing. |

|

| 1968 | 7 | 23:53 | −5 | The involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War intensifies, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 takes place, and the Six-Day War occurs in 1967. France and China, two nations which have not signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty, acquire and test nuclear weapons (the 1960 Gerboise Bleue and the 1964 596, respectively) to assert themselves as global players in the nuclear arms race. |

|

| 1969 | 10 | 23:50 | +3 | Every nation in the world, with the notable exceptions of India, Israel, and Pakistan, signs the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. |

|

| 1972 | 12 | 23:48 | +2 | The United States and the Soviet Union sign the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. |

|

| 1974 | 9 | 23:51 | −3 | India tests a nuclear device (Smiling Buddha), and SALT II talks stall. Both the United States and the Soviet Union modernize multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs). |

|

| 1980 | 7 | 23:53 | −2 | Unforeseeable end to deadlock in American–Soviet talks as the Soviet–Afghan War begins. As a result of the war, the U.S. Senate refuses to ratify the SALT II agreement. |

|

| 1981 | 4 | 23:56 | −3 | The Soviet war in Afghanistan toughens the U.S.' nuclear posture. U.S. President Jimmy Carter withdraws the United States from the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow. The Carter administration considers ways in which the United States could win a nuclear war. Ronald Reagan becomes President of the United States, scraps further arms reduction talks with the Soviet Union, and argues that the only way to end the Cold War is to win it. Tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union contribute to the danger of nuclear annihilation as they each deploy intermediate-range missiles in Europe. The adjustment also accounts for the Iran hostage crisis, the Iran–Iraq War, China's atmospheric nuclear warhead test, the declaration of martial law in Poland, apartheid in South Africa, and human rights abuses across the world.[30][31] |

|

| 1984 | 3 | 23:57 | −1 | Further escalation of the tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, with the ongoing Soviet–Afghan War intensifying the Cold War. U.S. Pershing II medium-range ballistic missile and cruise missiles are deployed in Western Europe.[30] Ronald Reagan pushes to win the Cold War by intensifying the arms race between the superpowers. The Soviet Union and its allies (except Romania) boycott the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, as a response to the U.S.-led boycott in 1980. |

|

| 1988 | 6 | 23:54 | +3 | In December 1987, the United States and the Soviet Union sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, to eliminate intermediate-range nuclear missiles, and their relations improve.[32] |

|

| 1990 | 10 | 23:50 | +4 | The fall of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain, along with the reunification of Germany, mean that the Cold War is nearing its end. |

|

| 1991 | 17 | 23:43 | +7 | The United States and Soviet Union sign the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I), the US announces the removal of many tactical nuclear weapons in September 1991, and the Soviet Union takes similar steps, as well as announcing the complete cessation of all nuclear testing in October 1991. The Bulletin editorial, published November 26, 1991, announces that "the 40-year-long East-West nuclear arms race is over."[33] One month after the Bullitin made this clock adjustment, the Soviet Union dissolves on December 26, 1991. This is the farthest from midnight the Clock has been since its inception. |

|

| 1995 | 14 | 23:46 | −3 | Global military spending continues at Cold War levels amid concerns about post-Soviet nuclear proliferation of weapons and brainpower. |

|

| 1998 | 9 | 23:51 | −5 | Both India (Pokhran-II) and Pakistan (Chagai-I) test nuclear weapons in a tit-for-tat show of aggression; the United States and Russia run into difficulties in further reducing stockpiles. |

|

| 2002 | 7 | 23:53 | −2 | Little progress on global nuclear disarmament. United States rejects a series of arms control treaties and announces its intentions to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, amid concerns about the possibility of a nuclear terrorist attack due to the amount of weapon-grade nuclear materials that are unsecured and unaccounted for worldwide. |

|

| 2007 | 5 | 23:55 | −2 | North Korea tests a nuclear weapon in October 2006,[34] Iran's nuclear ambitions, a renewed American emphasis on the military utility of nuclear weapons, the failure to adequately secure nuclear materials, and the continued presence of some 26,000 nuclear weapons in the United States and Russia.[4] After assessing the dangers posed to civilization, climate change was added to the prospect of nuclear annihilation as the greatest threats to humanity.[35] |

|

| 2010 | 6 | 23:54 | +1 | Worldwide cooperation to reduce nuclear arsenals and limit effect of climate change.[13] The New START agreement is ratified by both the United States and Russia, and more negotiations for further reductions in the American and Russian nuclear arsenal are already planned. The 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen results in the developing and industrialized countries agreeing to take responsibility for carbon emissions and to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius. |

|

| 2012 | 5 | 23:55 | −1 | Lack of global political action to address global climate change, nuclear weapons stockpiles, the potential for regional nuclear conflict, and nuclear power safety.[36] |

|

| 2015 | 3 | 23:57 | −2 | Concerns amid continued lack of global political action to address global climate change, the modernization of nuclear weapons in the United States and Russia, and the problem of nuclear waste.[37] |

|

| 2017 | 2+1⁄2 | 23:57:30 | −1⁄2 (−30 s) |

United States President Donald Trump's comments over nuclear weapons, the threat of a renewed arms race between the U.S. and Russia, and the expressed disbelief in the scientific consensus over climate change by the Trump administration. This is the first setting not to express a full minute figure.[38][39][40][41][20] |

|

| 2018 | 2 | 23:58 | −1⁄2 (−30 s) |

Failure of world leaders to deal with looming threats of nuclear war and climate change. This is the clock's third closest approach to midnight, matching that of 1953.[42] In 2019, the Bulletin reaffirmed the "two minutes to midnight" time, citing continuing climate change and Trump administration's abandonment of U.S. efforts to lead the world toward decarbonization; U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty; U.S. and Russian nuclear modernization efforts; information warfare threats and other dangers from "disruptive technologies" such as synthetic biology, artificial intelligence, and cyberwarfare.[43] |

|

| 2020 | 1+2⁄3 (100 s) |

23:58:20 | −1⁄3 (−20 s) |

Failure of world leaders to deal with the increased threats of nuclear war, such as the end of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) between the United States and Russia as well as increased tensions between the U.S. and Iran, along with the continued neglect of climate change. Announced in units of seconds, instead of minutes; this is the clock's second closest approach to midnight, exceeding that of 1953 and 2018.[44] The Bulletin concluded by stating that the current issues causing the adjustment are "the most dangerous situation that humanity has ever faced". In the annual statements for 2021 and 2022, issued in January of each year, the Bulletin left the "100 seconds to midnight" time setting unchanged.[45][46][47] |

|

| 2023 | 1+1⁄2 (90 s) |

23:58:30 | −1⁄6 (−10 s) |

Due largely–but not exclusively–to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the increased risk of nuclear escalation stemming from the conflict. Russia suspended its participation in the last remaining nuclear weapons treaty between it and the United States, New START.[48] Russia also brought its war to the Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia nuclear reactor sites, violating international protocols and risking widespread release of radioactive materials. North Korea resumed its nuclear rhetoric, launching an intermediate-range ballistic missile test over Japan in October 2022. Continuing threats posed by the climate crisis and the breakdown of global norms and institutions set up to mitigate risks associated with advancing technologies and biological threats such as COVID-19 also contributed to the time setting.[7] This setting remained unchanged the next year, 2024, thus remaining the closest to midnight the Clock has been since its inception.[49] |

|

In popular culture

[edit]- "Seven Minutes to Midnight", a 1980 single by Wah! Heat, refers to that year's change of the Doomsday Clock from nine to seven minutes to midnight.

- Australian rock band Midnight Oil's 1984 LP Red Sails in the Sunset features a song called "Minutes to Midnight", and the album's cover shows an aerial-view rendering of Sydney after a nuclear strike.

- The title of Iron Maiden's 1984 song "2 Minutes to Midnight" is a reference to the Doomsday Clock.[50][51]

- The Doomsday Clock appears in the beginning of the 1985 music video for "Russians" by Sting.

- The 1986 short story "The End of the Whole Mess" by Stephen King refers to the Doomsday Clock being set at fifteen seconds before midnight due to elevated geopolitical tension.[52]

- The Doomsday Clock was a recurring visual theme in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's seminal Watchmen graphic novel series (1986–87), its 2009 film adaptation, and its 2019 television miniseries sequel.[51] Additionally its sequel series, which takes place in the main DC Universe, borrows the title.

- The title of Linkin Park's 2007 album Minutes to Midnight is a reference to the Doomsday Clock.[53] Their music video for "Shadow of the Day" from Minutes to Midnight, represents the Doomsday Clock as an actual clock with it reaching midnight at the end of the video.

- In the Flobots' song "The Circle in the Square", the lyrics say "the clock is now 11:55 on the big hand", which was the Doomsday Clock's setting in 2012 when the song was released.[54]

- The title of the 1982 Doctor Who episode "Four to Doomsday" references the Doomsday Clock. In the 2017 episode "The Pyramid at the End of the World", the Monks changed every clock in the world to three minutes to midnight as a warning about what will happen if humanity does not accept their help. Representatives of the three most powerful armies on Earth agreed not to fight each other, believing a potential war is the catastrophe. However, the clock remained displaying two minutes to midnight. After the Doctor averted the true catastrophe - an accidental bacteriological disaster, the clock began moving backwards.[55]

- The Doomsday Clock is featured in Yael Bartana's What if Women Ruled the World, which premiered on July 5, 2017 at the Manchester International Festival.[56]

- One minute to midnight on the Doomsday Clock is heavily referenced in the grime/punk crossover song "Effed" by Nottingham rapper Snowy and Jason Williamson of Sleaford Mods. Because of the track's political content, there was an initial reluctance from mainstream radio stations to play the track before the 2019 United Kingdom general election. However, the track was later championed by a number of BBC Radio DJs, including punk innovator Iggy Pop.[57][58][59]

- In the Criminal Minds season 13 episode "The Bunker", the unsubs abduct women using the Doomsday Clock.

- The Madam Secretary season 2 episode "On the Clock" features the Doomsday Clock, as the characters try to keep it from moving forward.

- The character Bezel in Chikn Nuggit is a personification of the Doomsday Clock.

See also

[edit]- Apocalypticism

- The Bomb (film), a 2015 documentary film about the history of nuclear weapons

- Climate apocalypse

- Climate Clock

- DEFCON

- Doomsday device

- Eschatology

- Extinction symbol

- Metronome, a climate clock as public artwork showing the time remaining until the Earth's carbon budget is used up

- Mutual assured destruction

- Nuclear terrorism

- Svalbard Global Seed Vault

- World Scientists' Warning to Humanity

References

[edit]- ^ "Science and Security Board". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Morrison, R. (January 23, 2024). Doomsday Clock is 90 seconds to midnight as experts warn “ai among the biggest threats” to humanity. Tom’s Guide. https://www.tomsguide.com/news/ai-a-threat-to-the-end-of-the-world-doomsday-clock-stays-at-90-seconds-to-midnight

- ^ Stover, Dawn (September 26, 2013). "How Many Hiroshimas Does it Take to Describe Climate Change?". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013.

- ^ a b "'Doomsday Clock' Moves Two Minutes Closer To Midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 17, 2007. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ a b "Doomsday Clock 2019 Time". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 24, 2019. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ a b James, Sara (January 24, 2020). "'If there's ever a time to wake up, it's now': Doomsday Clock moves 20-seconds closer to midnight". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Doomsday Clock set at 90 seconds to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 24, 2023. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Starkey, Sarah (January 23, 2024). "PRESS RELEASE: Doomsday Clock remains at 90 seconds to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Doomsday Clock moving closer to midnight?". The Spokesman-Review. October 16, 2006. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "The Doomsday Clock". Southeast Missourian. February 22, 1984. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Running the 'Doomsday Clock' is a full-time job. Really". CNN. January 26, 2018. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "Doomsday Clock Symposium". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Timeline". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 2015. Archived from the original on June 24, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "A Timeline of Conflict, Culture, and Change". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ "Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950". Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. 2013. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- ^ "5th Doomsday Clock Symposium". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Doomsday Clock ticks closer to midnight". The Washington Post. January 10, 2012. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ^ "Doomsday Clock Moves Closer To Midnight, We're 2 Minutes From World Annihilation". The Two-Way. NPR. January 25, 2018. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Barasch, Alex (January 26, 2018). "What The Doomsday Clock Doesn't Tell Us". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c "The Doomsday Clock Is Reset: Closest To Midnight Since The 1950s". NPR.org. Archived from the original on November 27, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Reynolds, Emily (January 25, 2018). "What is the Doomsday Clock and why does it matter?". Wired. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Koran, Laura (January 25, 2018). "'Doomsday clock' ticks closer to apocalyptic midnight". CNN. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Chan, Sewell (2018). "Doomsday Clock Is Set at 2 Minutes to Midnight, Closest Since 1950s". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Is the Doomsday Clock Still Relevant?". Live Science. February 24, 2016. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Pinker, Steven (2019). Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. Penguin. pp. 308–11. ISBN 978-0-14-311138-2.

- ^ "Precision Prediction". National Review. January 18, 2010. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "Why the Doomsday Clock is an idiotic indicator the world's media should ignore". National Post. January 25, 2018. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Doomsday Clock moves closer to midnight". CBS News. January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "The Famed 'Doomsday Clock' Is Little More Than A Liberal Angst Meter". Investor's Business Daily. January 25, 2019. Archived from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "Doomsday Clock at 3'til midnight". The Daily News. December 21, 1983. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Feld, Bernard T. (January 1981). "The hands move closer to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 37 (1): 1. Bibcode:1981BuAtS..37a...1F. doi:10.1080/00963402.1981.11458799. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ "Hands of the 'Doomsday Clock' turned back three minutes". Reading Eagle. December 17, 1987. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Editorial Board (November 26, 1991). Moore, Mike (ed.). "A New Era (Editorial)". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 47 (10 (December 1991)): 3.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "The North Korean nuclear test". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 2009. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ^ "Nukes, climate push 'Doomsday Clock' forward". NBC News. January 15, 2012. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "Doomsday Clock moves to five minutes to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 14, 2013. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ Casey, Michael (January 22, 2015). "Doomsday Clock moves two minutes closer to midnight". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Science and Security Board Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (August 9, 2011). "It is two and a half minutes to midnight" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ "Board moves the clock ahead". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (Press release). January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Holley, Peter; Ohlheiser, Abby; Wang, Amy B. "The Doomsday Clock just advanced, 'thanks to Trump': It's now just 2⁄1 minutes to 'midnight.'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Bromwich, Jonah Engel (January 26, 2017). "Doomsday Clock Moves Closer to Midnight, Signaling Concern Among Scientists". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Bever, Lindsey; Kaplan, Sarah; Ohlheiser, Abby (January 25, 2018). "The Doomsday Clock is now just 2 minutes to 'midnight,' the symbolic hour of the apocalypse". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Mecklin, John (January 24, 2019). "A new abnormal: It is still 2 minutes to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (January 23, 2020). "Doomsday clock: Humanity closer to annihilation than ever before, scientists say; Clock is now set to 100 seconds to midnight, experts announce". The Independent. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ "Current Time". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "2021 Doomsday Clock Statement" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 27, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ "2022 Doomsday Clock Statement". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 20, 2022. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (February 21, 2023). "Putin's Move on Nuclear Treaty May Signal End to Formal Arms Control". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Starkey, Sarah (January 23, 2024). "Doomsday Clock remains at 90 seconds to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (Press release). Retrieved January 23, 2024.

- ^ Bowen, LB (January 24, 2017). "Doomsday Clock: Iron Maiden – Two Minutes to Midnight". OnStage Magazine. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Ihnat, Gwen (February 23, 2017). "The people behind the Doomsday Clock explain why we're so close to midnight". AUX (The A.V. Club). Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ King, Stephen (1993). Nightmares & Dreamscapes. New York: Scribner. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-5011-9203-6.

The saber-rattling had become a din. On the last day of the old year the Scientists for Nuclear Responsibility had set their black clock to fifteen seconds before midnight.

- ^ Rodriguez, Dana (May 25, 2007). "Linkin Park Makes 'Minutes to Midnight' Count". BMI.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ^ Flobots – The Circle in the Square, archived from the original on December 9, 2019, retrieved December 9, 2019

- ^ "The Pyramid at the End of the World: The Fact File". BBC. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ Judah, Hettie (July 10, 2017). "What If Women Ruled the World? review – Kubrick meets covfefe as catastrophe strikes". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ ""EFFED" by Snowy feat. Jason Williamson". genius.com. November 21, 2019. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ "Snowy & Jason Williamson (Ft. Jason Williamson & Snowy) – EFFED". Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ "BBC Radio 6 Music - Iggy Pop, Iggy Confidential with a track from his album of 2019". BBC. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

External links

[edit] Media related to Doomsday Clock at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Doomsday Clock at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Doomsday Clock at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Doomsday Clock at Wikiquote- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- Doomsday Clock homepage

- Timeline of the Doomsday Clock