Vergina

Vergina

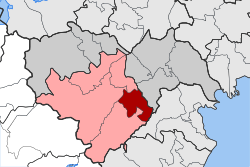

Βεργίνα | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 40°29′N 22°19′E / 40.483°N 22.317°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Imathia |

| Municipality | Veroia |

| Area | |

| • Municipal unit | 69.0 km2 (26.6 sq mi) |

| Lowest elevation | 120 m (390 ft) |

| Population (2021)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 2,034 |

| • Municipal unit density | 29/km2 (76/sq mi) |

| • Community | 1,096 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official name | Archaeological Site of Aigai (modern name Vergina) |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii |

| Reference | 780 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

| Area | 1,420.81 ha |

| Buffer zone | 4,811.73 ha |

Vergina (Greek: Βεργίνα, Vergína [verˈʝina]) is a small town in Northern Greece, part of the Veria municipality in Imathia, Central Macedonia. Vergina was established in 1922 in the aftermath of the population exchanges after the Treaty of Lausanne and was a separate municipality until 2011, when it was merged with Veroia under the Kallikratis Plan.

Vergina is best known as the site of ancient Aigai (Ancient Greek: Αἰγαί, Aigaí, Latinized: Aegae), the first capital of Macedon. In 336 BC Philip II was assassinated in Aigai's theatre and his son, Alexander the Great, was proclaimed king. While the resting place of Alexander the Great is unknown, researchers uncovered three tombs at Vergina in 1977 – referred to as tombs I, II and III.

Tomb I contained Philip II, Alexander the Great's father, tomb II belonged to Philip III of Macedon, Alexander the Great's half-brother, while tomb III contained Alexander IV, Alexander the Great's son.[2][3]

Tomb I had been looted; Tombs II and III were intact and contained an array of burial goods. The ancient town was also the site of an extensive royal palace. The archaeological museum of Vergina was built to house all the artifacts found at the site and is one of the most important museums in Greece.[4]

Aigai has been awarded UNESCO World Heritage Site status as "an exceptional testimony to a significant development in European civilization, at the transition from classical city-state to the imperial structure of the Hellenistic and Roman periods".[4]

History

[edit]This article duplicates the scope of other articles. (February 2024) |

The area within 7 km of the later city was occupied by villages forming an important population centre by 1000BC. This has been shown by archaeology since 1995. Aigai followed a similar development as other ancient Greek cities.[5]

In the 7th century BC, the Temenids' dominance led to the Macedonians expanding and subduing local populations until the end of the 6th century BC, and establishing the dynasty at Aigai.

Ancient sources give conflicting accounts of the origins of the Argead dynasty.[6][7] Alexander I is the first truly historic figure and, based on the line of succession, the beginnings of the Macedonian dynasty have been traditionally dated to 750 BC.[8] Herodotus says[9] that the Argead dynasty was an ancient Greek royal house led by Perdiccas I who fled from Argos in about 650 BC.[10]

Aigai is the name of several ancient Greek cities (see Aegean Sea#Etymology). Their name is often derived from the name of a legendary founder, Aegeus. In the case of this city, it is also etymologized as "city of goats" (from αἴξ, aíks, "goat") by Diodorus Siculus, who reports it was named so by Perdiccas I who was advised by the Pythian priestess to build the capital city of his kingdom where goats led him.[11]

Archaeologic evidence shows that Aigai developed as an organized collection of villages, spatially representing the aristocratic structure of tribes centred on the power of the king. It remained so throughout its history.[12] Indeed, Aigai never became a large city and most of its inhabitants lived in surrounding villages.[13] The walled asty (acropolis) was built at the centre of Aigai.[14]

From Aigai the Macedonians spread to the central part of Macedonia and displaced the local population of Pierians.

From 513 to 480 BC Aigai was part of the Persian Empire, but Amyntas I managed to keep its relative independence, avoid satrapy and extend its possessions.

In the first half of the 5th century BC Aigai became the capital of Macedonia. Life reached unseen levels of luxury and to meet the needs of the court merchants from all over the ancient world brought to Aigai valuable goods including perfume, carved ornaments and jewellery.[15] The city wall was built in the 5th century, probably by Perdiccas II. At the end of the 5th century Archelaus I brought to his court artists, poets, and philosophers from all over the Greek world; for example, it was at Aigai that Euripides wrote and presented his last tragedies.

At the beginning of the 4th century BC, Archelaus transferred the Macedonian capital northeast to Pella on the central Macedonian plain.[16] Nevertheless, Aigai retained its role as the sacred city of the Macedonian kingdom, the site of the traditional cult centres, a royal palace and the royal tombs. For this reason it was here that Philip II was attending the wedding of his daughter Cleopatra to King Alexander of Epirus when he was murdered by one of his bodyguards in the theatre.[17] His was the most lavish funeral ceremony of historic times held in Greece. Laid on an elaborate gold and ivory deathbed wearing his precious golden oak wreath, the king was surrendered, like a new Hercules, to the funeral pyre.

The bitter struggles between the heirs of Alexander in the 3rd century adversely affected the city; in 276 BC Gallic mercenaries of Pyrrhus plundered many of the tombs.

After the overthrow of the Macedonian kingdom by the Romans in 168 BC, both old and new capitals were destroyed, the walls pulled down and all buildings burned.[12] In the 1st century AD, a landslide destroyed what had been rebuilt (excavations establish that parts were still inhabited then).[18] In the 2nd to 5th centuries AD the population gradually moved from the foothills of the Pierian range to the plain, and all that remained was a small settlement whose name alone Palatitsia (palace) indicated its former importance.

The modern settlement of Vergina was established in 1922, between two preexisting villages, "Kutlesh" (Κούτλες, Koútles) and "Barbes" (Μπάρμπες, Bármpes), formerly part of the Ottoman Beylik of Palatitsia. In the 19th century, both Kutlesh and Barbes were Greek villages in the Ber Kaza of the Ottoman Empire. Several inhabitants of the two villages took part in the Greek uprising of 1821. Alexander Sinve (Les Grecs de l'Empire Ottoman. Etude Statistique et Ethnographique) wrote in 1878 that 120 Greeks lived in Barbas. According to the statistics of Vasil Kanchov ("Macedonia. Ethnography and Statistics"), in 1900, 60 Greek Christians lived in Kutlesh and 50 in Barbes. The town of Vergina was settled in the course of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey following the Treaty of Lausanne, by Greek families from Asia Minor. The name "Vergina" was a suggestion by the metropolitan of Veroia, chosen from a legendary queen Vergina (Bergina), who was said to have ruled somewhere north of the Haliacmon and to have had her summer palace near Palatitsia.[19] Vergina was a separate municipality from 1922 until 2011, when it was incorporated into Veroia.[20] The population of Vergina municipality as of 2011 was 2,464, of whom 1,242 lived in Vergina proper.

Archaeology

[edit]Archaeologists were interested in the burial mounds around Vergina as early as the 1850s, supposing that the site of Aigai was in the vicinity. Excavations began in 1861 under the French archaeologist Léon Heuzey, sponsored by Napoleon III. Parts of a large building that was considered to be one of the palaces of Antigonus III Doson (263–221 BC), partly destroyed by fire, were discovered near Palatitsa, which preserved the memory of a palace in its modern name. However, the excavations had to be abandoned because of the risk of malaria. The excavator suggested that this was the site of the ancient city Valla, a view that prevailed until 1976.[21]

In 1937, the University of Thessaloniki resumed the excavations. More ruins of the ancient palace were found, but the excavations were abandoned on the outbreak of war with Italy in 1940. After the war the excavations were resumed, and during the 1950s and 1960s the rest of the royal capital was uncovered, including the theatre.

The Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos became convinced that a hill called the Great Tumulus (Μεγάλη Τούμπα) concealed the tombs of the Macedonian kings. In 1977, Andronikos undertook a six-week dig at the Great Tumulus and found four buried tombs, two of which had never been disturbed. Andronikos identified that these were the burial sites of the kings of Macedon, including the tomb of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great (Tomb II) and also of Alexander IV of Macedon, son of Alexander the Great and Roxana (Tomb III). This view was challenged by some archaeologists,[22][23][24] and in 2010 research based on detailed study of the skeletons, vindicated Andronikos and supports the evidence of facial asymmetry caused by a possible trauma of the cranium of the male, evidence that is consistent with the history of Philip II.[25][26] From 1987 the burial cluster of the queens was discovered including the tomb of Queen Eurydice. In March 2014, five more royal tombs were discovered in Vergina, possibly belonging to Alexander I of Macedon and his family or to the family of Cassander of Macedon. Some artifacts excavated at Vergina may be treated as influenced by Asian practices or even imported from Achaemenid Persia in late 6th and early 5th centuries BC,[27] which is during the time Macedon was under the Persian sway.

In 2023, nearly 50 years later, a study led by professor of anthropology at the Democritus University of Thrace Antonios Bartsiokas 'conclusively' revealed that the skeleton long identified as belonging to Alexander IV of Macedon is in fact his father Philip II of Macedon, and vice versa: Tomb I contained Philip II, Alexander the Great's father, tomb II belonged to Philip III of Macedon, Alexander the Great's half-brother, while tomb III contained Alexander IV, Alexander the Great's son.[28] Tomb I also contained the remains of a woman and a baby, who Bartsiokas identified as Philip II's young wife Cleopatra Eurydice and their newborn child. Cleopatra Eurydice was assassinated along with her newborn child.[29]

Royal burial cluster of Philip II

[edit]

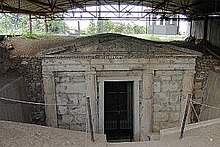

The museum of the tumulus of Philip II, which was inaugurated in 1993, was built over the tombs leaving them in situ and showing the tumulus as it was before the excavations. Inside the museum there are four tombs and one small temple, the heroon built as the temple for the burial cluster of Philip II. The two most important tombs (II and III) were not sacked and contained the main treasures of the museum. Tomb II of Philip II, the father of Alexander was discovered in 1977 and was separated in two rooms. The main room included a marble chest, and in it was the Golden Larnax made of 24-carat gold and weighing 11 kilograms (24 lb), embossed with the Vergina Sun symbol. Inside the golden larnax the bones of the dead were found and a golden wreath of 313 oak leaves and 68 acorns, weighing 717 grams (25.3 oz). In the room were also found the golden and ivory panoply of the dead, the richly carved burial bed on which he was laid and later burned and exquisite silver utensils for the funeral feast. Other magnificent items include several gold-adorned suits of armour, weapons, and bronze funeral utensils.

In the antechamber was another chest with another golden larnax containing the bones of a woman wrapped in a golden-purple cloth with a golden diadem decorated with flowers and enamel, indicating a queen (probably Philip's Thracian wife, Meda)[30] who by tradition sacrificed herself at the funeral. Also included was another burial bed partially destroyed by the fire and on it a golden wreath representing leaves and flowers of myrtle. Above the Doric order entrance of the tomb is a magnificent wall painting measuring 5.6 metres (18 ft) representing a hunting scene, believed to be the work of the celebrated Philoxenos of Eretria, and thought to show Philip and Alexander.

Next to him in Tomb I a distinctive member of his family (probably Nicesipolis, another of his queens), was buried just a few years before in a cist grave, found unfortunately plundered. The only wall painting in the tomb pictures the Abduction of Persephone by the God of the Underworld, the silent Demeter and the three unprejudiced Fates with Hermes, the Guide of Souls, leading the way, and a scared nymph witnessing the horrifying event. This is a unique example of ancient painting, believed to be the work of the famous painter Nicomachus of Thebes, as well as one of the few surviving depictions of the ancient mystic views of afterlife.

In 1978 Tomb III was discovered, also near the tomb of Philip, which is thought to belong to Alexander IV of Macedon, son of Alexander the Great, murdered 25 years after Philip's assassination. It is slightly smaller than Tomb II and was also not sacked. It was also arranged in two parts, but only the main room contained a cremated body. On a stone pedestal was found a fine silver hydria, which contained the cremated bones, and on it a golden oak wreath. There were also exquisite silver utensils and weaponry indicating royal status. A narrow frieze with a chariot race by a great painter decorated the walls of the tomb. The remains of a wooden mortuary couch adorned with gold and ivory is notable for an exquisite representation of Dionysos with a flute-player and a satyr.

Tomb IV, discovered in 1980, had an impressive entrance with four Doric columns though is heavily damaged and may have contained valuable treasures. It was built in the 4th century BC and may have belonged to Antigonus II Gonatas.

The great tumulus was constructed at the beginning of the third century BC (by Antigonos Gonatas) perhaps over smaller individual tumuli to protect the royal tombs from further pillaging after marauding Galati had looted and destroyed the cemetery. The hill material contained many earlier funeral stele.

Palace of Aigai

[edit]The most important building discovered is the monumental palace. Located on a plateau directly below the acropolis, this building of two or perhaps three stories is centred on a large open courtyard flanked by Doric colonnades. On the north side was a large gallery with a view of the stage of the neighbouring theatre and the whole Macedonian plain. The palace was sumptuously decorated, with mosaic floors, painted plastered walls, and fine relief tiles. The masonry and architectural members were covered with high-quality marble stucco. Excavations have dated its construction to the reign of Philip II,[30] even though he also had a palace in the capital, Pella. It has been suggested that the building was designed by the architect Pytheos of Priene, known for his work on the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and for his views on urban planning and architectural proportions). The theatre, also from the second half of the 4th century BC, was closely associated with the palace.

Nearly 30 large columns that surrounded the palace's main peristyle have been reconstructed, some towering to a height of 25 ft.[31] The frieze on the peristyle's southern section has also been reconstructed.[32] Over 5,000 square feet of mosaics depicting a range of scenes, including the ravishing of Europa and motifs from nature have been carefully conserved.

The Palace of Aigai is the largest building of classical Greece and is the location where Alexander the Great was proclaimed king in 336 BC.[33]

The Palace of Aigai reopened to the public in January 2024 after an extensive 16 year restoration.[34]

Other tombs

[edit]

The cemetery of the tumuli[35] extends for over 3 km (1.9 mi) and contains over 500 grave-mounds of significant wealth, some dating as early as the 11th century BC.

To the north-west of the ancient city is the important group of tombs from the 6th and 5th centuries BC belonging to members of the Macedonian dynasty and their courts.

The Cluster of the Queens includes cist and pit tombs dating to the Greco-Persian Wars era, two of which probably belong to the mother and spouse of Alexander I: the all golden "Lady of Aigai" and her female relative, in whose funeral at least twenty-six small terracotta statues. One from around 340 BC with an imposing marble throne is identified as that of Eurydice, mother of Philip II.

The so-called "Ionic Tomb" or "Rhomaios's Tomb", named after its excavator, Konstantinos Rhomaios, is an elegant Macedonian tomb with an Ionic facade consisting of four engaged columns crowned by a painted floral frieze, now no longer visible because of weathering. It contained a marble throne with armrests supported by sphinxes.[36]

Gallery

[edit]-

"Hades abducting Persephone" fresco

-

Remains from the King's tomb

-

Remains from Queen's tomb

-

Great Tumulus of Aigai

-

Tomb III, probably belonged to Alexander IV of Macedon

-

Manolis Andronikos in memoriam

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2021, Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός κατά οικισμό" [Results of the 2021 Population - Housing Census, Permanent population by settlement] (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 29 March 2024.

- ^ Antonis Bartsiokas, Juan Luis Arsuaga, Nicholas Brandmeir: The identification of the Royal Tombs in the Great Tumulus at Vergina, Macedonia, Greece: A comprehensive review. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 52, December 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.104279

- ^ Antonis Bartsiokas (2024): The Identification of the Sacred “Chiton” (Sarapis) of Pharaoh Alexander the Great in Tomb II at Vergina, Macedonia, Greece. Journal of Field Archaeology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2024.2409503

- ^ a b "Archaeological Site of Aigai (modern name Vergina)". UNESCO World Heritage Convention. United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Angeliki Kottaridi, Aegae, the Macedonian metropolis, Treasures from the Royal Capital of Macedon, Ashmolean Museum 2011. p 155

- ^ Justin: Historiarum Philippicarum

- ^ Strabo. Geography, Book 7

- ^ Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Griffith, Guy Thompson (1972). A History of Macedonia: Historical Geography and Prehistory I. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Herodotus. Histories, 8.137.8

- ^ Ring, Trudy (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 753. ISBN 1-884964-02-8.

- ^ Sikeliotis, Diodoros or Diodorus Siculus 80–20 B.C., Historical, 7.16: "and then/Where thou shalt see white-horned goats, with fleece/Like snow, resting at dawn, make sacrifice/Upon the blessed gods upon that spot/And raise the chief city of a state."

- ^ a b "Timeline – Museum of Royal Tombs of Aigai -Vergina". www.aigai.gr. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "Aigai: The royal metropolis of the Macedonians – Multimedia". Latsis Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "The ancient city – Museum of Royal Tombs of Aigai-Vergina". www.aigai.gr. Archived from the original on 2014-09-11.

- ^ Angeliki Kottaridi, Aegae, the Macedonian metropolis, Treasures from the Royal Capital of Macedon, Ashmolean Museum 2011. p.158

- ^ Roisman, Joseph (December 2010). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Diodorus Siculus — Book XVI Chapters 66‑95". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "Vergina 2012: The excavation at the 'Tsakiridis' Section": Styliani Drougou, professor of History and Archaeology Department, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. http://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/vergina-2012-excavation-at-tsakiridis.html

- ^ Alexander Eliot, The Penguin Guide to Greece (1991), p. 291.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ^ M. Andronikos,"Anaskafi sti Megali Toumpa tis Verginas" Archaiologica Analekta Athinon 9(1976), 127–129.

- ^ Borza, Eugene N. (1999). Before Alexander: Constructing Early Macedonia. Publications of the Association of Ancient Historians, 6. Claremont, CA: Regina Books. pp. 68–74. ISBN 0941690970 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Bartsiokas, Antonis (21 April 2000). "The Eye Injury of King Philip II and the Skeletal Evidence from the Royal Tomb II at Vergina". Science. 288 (5465): 511–514. Bibcode:2000Sci...288..511B. doi:10.1126/science.288.5465.511. JSTOR 3075009. PMID 10775109.

- ^ Borza, Eugene N.; Palagia, Olga (2007). "The Chronology of the Macedonian Royal Tombs at Vergina". Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. 122: 81–125. ISSN 0070-4415.

- ^ Bristol, University of. "2010: Vergina Tomb II - News - University of Bristol". www.bris.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Musgrave, J.; Prag, A. J. N. W.; Neave, R.; Fox, R. L. & White, H. (2010). "The Occupants of Tomb II at Vergina. Why Arrhidaios and Eurydice must be excluded". International Journal of Medical Sciences. 7 (6): s1–s15.

- ^ Roisman & Worthington 2011, p. 345.

- ^ Antonis Bartsiokas, Juan Luis Arsuaga, Nicholas Brandmeir: The identification of the Royal Tombs in the Great Tumulus at Vergina, Macedonia, Greece: A comprehensive review. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 52, December 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.104279

- ^ Antonis Bartsiokas (2024): The Identification of the Sacred “Chiton” (Sarapis) of Pharaoh Alexander the Great in Tomb II at Vergina, Macedonia, Greece. Journal of Field Archaeology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2024.2409503

- ^ a b "Αιγές (Βεργίνα) – Museum of Royal Tombs of Aigai -Vergina". aigai.gr. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Mandal, Dattatreya (28 February 2018). "Philip II's massive palace at Aigai to be opened for the public in May". Realm of History. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Philip II's palace at Aigai to open to the public in May". The Greek Observer. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Kantouris, Derek Gatopoulos and Costas (2024-01-06). "Greece unveils palace where Alexander the Great became king". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ Kantouris, Derek Gatopoulos and Costas (2024-01-06). "Greece unveils palace where Alexander the Great became king". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ The Cemetery of the Tumuli, https://www.aigai.gr/en/archaeological-site-of-aigai/necropolis Archived 2022-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Drougou, Stella; Saatsoglou-Paliadelē, Chrysoula (2006). Vergina: The Land and Its History. Athens. pp. 186–190. ISBN 960-89121-1-3. OCLC 79447186.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

References

[edit]- Drougou S., Saatsoglou Ch., Vergina: Reading around the archaeological site, Ministry of Culture, 2005.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5163-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Barr-Sharrar, Beryl (2013-10-01) Some Comprehensive New Publications on Ancient Macedonia, American Journal of Archaeology, 117, pp. 599–608. doi:10.3764/aja.117.4.0599

- Drougou, Stella; Saatsoglou-Paliadelē, Chrysoula. Vergina: wandering through the archaeological site (2004), Athens: Archaeological Receipts Fund, Direction of Publications OCLC 80765321.

- Drougou, S. Macedonian Metallurgy: an Expression of Royalty, L. Fox (ed.), Heracles to Alexander the Great, Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2011.

- Romero, Ramona V. (2003) Vergina: tomb II and the Great Tumulus; a reevaluation of identities.

- Films for the Humanities & Sciences. The glory of Macedonia, 2000, DVD, OCLC 1100218182.

External links

[edit]- Small heads of Alexander the Great and his mother Olympias made of ivory, Vergina - by Kantonsschule Zürcher Unterland (KZU) (in German)(Archived)

- Golden larnax, Vergina - KZU (in German)(Archived)

- Archaeological Site of Aigai (modern name Vergina) - UNESCO World Heritage Centre