Spiritual Exercises

The Spiritual Exercises (Latin: Exercitia spiritualia), composed 1522–1524, are a set of Christian meditations, contemplations, and prayers written by Ignatius of Loyola, a 16th-century Spanish Catholic priest, theologian, and founder of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits).

Divided into four thematic "weeks" of variable length, they are designed to be carried out over a period of 28 to 30 days.[1] They were composed with the intention of helping participants in religious retreats to discern the will of God in their lives, leading to a personal commitment to follow Jesus whatever the cost.[2]: 98 Their underlying theology has been found agreeable to other Christian denominations who make use of them[3] and also for addressing problems facing society in the 21st century.[4]

Editions

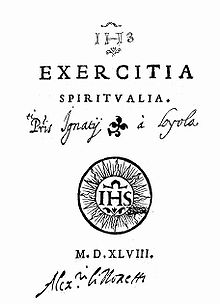

[edit]The first printed edition of the Spiritual Exercises was published in Latin in 1548, after being given papal approval by Pope Paul III.[5] However, Ignatius's manuscripts were in Spanish, so this first edition was in fact a translation, although it was made during Ignatius's lifetime and with his approval. Many subsequent editions in Latin and in various other languages were printed early on with widely differing texts.[6]

Archival work on the authentic text of the Spiritual Exercises was undertaken at the initiative of the 19th century Jesuit Superior General Jan Roothaan, who himself published a translation and notes from the original manuscripts of St. Ignatius. The culmination of this work was a "critical edition" of the Exercises published by the Jesuit order in 1919, in the Monumenta Historica Societatis Jesu series.[7] A critical edition from 1847 that incorporates Roothaan's studies can be found online.[8] An authoritative Spanish-Latin text, based on the critical edition, was published in Turin by Marietti, in 1928. This was edited by the editor of the critical edition, and included convenient marginal numbers for every section, which can be found in all contemporary editions (and inline in this article).

An English translation by Louis J. Puhl, S.J., published in 1951, has been widely used by Jesuits, spiritual directors, retreat leaders, and others in the English-speaking world. Puhl translated directly from studies based on the original manuscripts.[2]

Background

[edit]

After recovering from a leg wound incurred during the Siege of Pamplona in 1521, Ignatius made a retreat with the Benedictine monks at their abbey high on Montserrat in Catalonia, northern Spain, where he hung up his sword before the statue of the Virgin of Montserrat. The monks introduced him to the spiritual exercises of Garcias de Cisneros, which were based in large part on the teachings of the Brothers of the Common Life, the promoters of the "devotio moderna". From Montserrat, he left for Barcelona but took a detour through the town of Manresa, where he eventually remained for several months, continuing his convalescence at a local hospital. During this time he discovered The Imitation of Christ of Thomas à Kempis, the crown jewel of the "devotio moderna",[9] which however gave little grounding for an apostolic spirituality,[10] an omission Ignatius later tried to supply in his Constitutions with its focus on labor in the Lord's vineyard.[11] He also spent much of his time praying in a cave nearby, where he practiced rigorous asceticism. During this time Ignatius experienced a series of visions, and formulated the fundamentals of his Spiritual Exercises. He would later refine and complete the Exercises when he was a student in Paris.[12]

The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius form the cornerstone of Ignatian Spirituality: a way of understanding and living one's relationship with God in the world as practiced by members of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). Although he originally designed them to take place in the setting of a secluded retreat, during which those undergoing the exercises would be focused on nothing other than the Exercises, Ignatius also provided a model in his introductory notes for completing the Exercises over a longer period without the need of seclusion.[2]: 19 The Exercises were designed to be carried out while under the guidance of a spiritual director, but they were never meant only for monks or priests: Ignatius gave the Exercises for 15 years before he was ordained, and years before the Society of Jesus was founded. He saw them as an instrument for bringing about a conversion or change of heart, especially in the Reformation times in which he lived. After the Society of Jesus was formed, the Exercises became the central component of its training program. They usually take place during the first year of a two-year novitiate and during a final year of spiritual studies after ordination to the priesthood. The Exercises have also impacted the founders of other religious orders, even becoming central to their work.[13]

Ignatius considered the examen, or spiritual self-review, to be the most important way to continue to live out the experience of the Exercises after their completion.[14]

Spiritual viewpoint

[edit]Ignatius identified the various motives that lead a person to choose one course of action over another as "spirits".[15] A major aim of the Exercises is the development of discernment (discretio), the ability to discern between good and evil spirits. A good spirit can bring love, joy, peace, but also desolation to reveal the evil in one's present life. An evil spirit usually brings confusion and doubt, but may also prompt complacency to discourage change. The human soul is continually drawn in two directions: towards goodness but at the same time towards sinfulness.[2]: 313ff

According to the theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, "choice" is the center of the Exercises, and they are directed to choosing God's will, a deepening self-abandonment to God. The Exercises "have as their purpose the conquest of self and the regulation of one’s life in such a way that no decision is made under the influence of any inordinate attachment."[16]

"Discernment" is very important to Ignatian thought. Through the process of discernment, the believer is led toward a direct connection between one's thought and action and the grace of God. As such, discernment can be considered a movement toward mystical union with God, and it emphasizes the mystical experience of the believer. This aspect of the Spiritual Exercises reflects the trend toward mysticism in Catholic thought which flourished during the time of the Counter-Reformation (e.g., with Teresa of Ávila, Francis de Sales, and Pierre de Bérulle). However, while discernment can be understood as a mystical path, it is also more prosaically a method of subjective ethical thought, emphasizing the role of one's own mental faculties in deciding right and wrong.[2]: 313

| Part of a series on the |

| Society of Jesus |

|---|

|

| History |

| Hierarchy |

| Spirituality |

| Works |

| Notable Jesuits |

|

|

Typical methodology and structure

[edit]The original, complete form of the Exercises is a retreat of about 30 days in silence and solitude.[17] The Exercises are divided into four "weeks" of varying length with four major themes: sin and God's mercy, episodes in the life of Jesus, the passion of Jesus, and the resurrection of Jesus together with a contemplation on God's love. This last is often seen as the goal of Ignatian spirituality, to find God in all things.[2]: 235 The "weeks" represent stages in a process of wholehearted commitment to the service of God.

- First Week: Sin, and God's mercy

- Second Week: Episodes in the life of Jesus

- Third Week: The passion of Jesus

- Fourth Week: The resurrection of Jesus, and God's love

Morning, afternoon, and evening will be times of the examinations. The morning is to guard against a particular sin or fault, the afternoon is a fuller examination of the same sin or defect. There will be a visual record with a tally of the frequency of sins or defects during each day. In it, the letter 'g' will indicate days, with 'G' for Sunday. Three kinds of thoughts: "my own" and two from outside, one from the "good spirit" and the other from the "bad spirit".

Ignatius' book is not meant to be used by the retreatant but by a director or spiritual guide. Each day the exercitant uses the material proposed by the director for four or five hour-long periods, each followed by a review of how the period went. The exercitant reports back to the spiritual director who helps interpret the exercitant's experiences and proposes material for the next day. Ignatius observes that God "deals directly" with the well-disposed person and the director should not give advice to the retreatant that might interfere with God's workings.[2]: 15

After the first week Ignatius recommends a form of contemplation which he calls "application of the senses."[2]: 121–126 For this you “place yourself in a scene from the Gospels. Ask yourself, "What do I see? What do I hear? What do I feel, taste and smell?”[18] The purpose of these Exercises is that we might gain the empathy to "follow and imitate more closely our Lord."[2]: 109 From this comes the widespread use of the magis concept in Ignatian circles, pursuing spiritual growth and progress rather than sudden transformation.

Modern applications

[edit]The Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola are considered a classic work of spiritual literature.[16] Many Jesuits are ready to direct the general public in retreats based on the Exercises.

Since the 1980s there has been a growing interest in the Spiritual Exercises among people from other Christian traditions.[3] The Exercises are also popular among lay people[17] both in the Catholic Church and in other denominations, and lay organizations like the Christian life community place the Exercises at the center of their spirituality. The Exercises are seen variously as an occasion for a change of life[2]: 18 and as a school of contemplative prayer.

The most common way for laypersons to go through the Exercises now is a "retreat in daily life", which involves a five- to seven-month programme of daily prayer and meetings with a spiritual director.[17] Also called the "19th annotation exercises" based on a remark of St. Ignatius in the 19th "introductory observation" in his book, the retreat in daily life does not require an extended stay in a retreat house and the learned methods of discernment can be tried out on day-to-day experiences over time.[2]: 19

Also, some break the 30 days into two or three sections over a two-year period. Most retreat centers offer shorter retreats with some of the elements of the Spiritual Exercises. Retreats have been developed for specific groups of people, such as those who are married or engaged. Self-guided forms of the Exercises are also available, including online programs.[19][20]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Counsell, Michael. 2000 Years of Prayer, 2004, ISBN 1-85311-623-8 p. 203

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Louis J. Puhl, S.J. Translation - The Spiritual Exercises". Ignatian Spirituality. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Ignatian Spirituality & The Spiritual Exercises | Trinity Episcopal Church". trinityic.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Lessons in the Life of Prayer from Ignatius Loyola | National Review". National Review. 2018-08-11. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- ^ In the brief Pastoralis officii of 31 July 1548.

- ^ Sabau, Antoaneta. "Rewriting Through Translation: Some Textual Issues in the Vulgáta of the Ejercicios Espirituales by Ignatius Of Loyola" (PDF). Annual of Medieval Studies. 16: 155–165.

- ^ Monumenta Historica Societatis Jesu, Monumenta Ignatiana, Series Secunda: Exercitia Spiritualia. Madrid, 1919.

- ^ "The spiritual exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola". archive.org. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ De La Boullaye, Pinard. Ignatian Spirituality.

- ^ Balthasar, Hans Urs von. The Glory of the Lord V. Cambridge U. Press, 2001, p. 103. ISBN 978-0898702477.

- ^ "Vineyard in Ignatius' Constitutions" (PDF). Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "St. Ignatius Loyola - Saints & Angels - Catholic Online". Catholic Online. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "History | Oblates of the Virgin Mary". www.omvusa.org. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ "The Daily Examen - IgnatianSpirituality.com". Ignatian Spirituality. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ user1. "Discernment in a Nutshell". Ignatian Spirituality. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Löser, Werner. Hans Urs Von Balthasar. (David Schindler, ed.) Ignatius Press, 1991 ISBN 9780898703788

- ^ a b c lpignatian. "The Spiritual Exercises". Ignatian Spirituality. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- ^ "Father James Martin: An introduction to Ignatian contemplation". America Magazine. 21 September 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "Online Retreat in Everyday Life". onlineministries.creighton.edu. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "The Jesus Way: Practicing the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises". The Ignatian Spiritual Exercises. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

References

[edit]- Ignatius of Loyola, Spiritual Exercises, London: limovia.net, 2012. ISBN 978-1-78336-012-3.

- David L. Fleming, S.J. The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, A Literal Translation and A Contemporary Reading. St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1978. ISBN 0-912422-31-9.

- Timothy M. Gallagher, The Discernment of Spirits: An Ignatian Guide for Everyday Life. Crossroad, 2005.

- George E. Ganss, S.J. The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius: A Translation and Commentary. Chicago: Loyola Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8294-0728-6.

- C. G. Jung, Jung on Ignatius of Loyola's 'Spiritual Exercises'. (Princeton University 2023).

- Anthony Mottola, Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius. Image, 1964, ISBN 0-385-02436-3.

- Joseph A. Tetlow, The Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola. Crossroad, 2009.

- Ignatian contemplation: application of the senses

External links

[edit]Online text

- Puhl's translation

- Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- The Spiritual Exercises Audio from Librivox