Battle of the Nek

| Battle of the Nek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I Gallipoli Campaign | |||||||

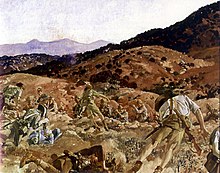

The charge of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade at the Nek, 7 August 1915 by George Lambert, 1924. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 600 | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 372 killed and wounded | At least 12 | ||||||

The Battle of the Nek (Turkish: Kılıçbayır Muharebesi) was a minor battle that took place on 7 August 1915, during the Gallipoli campaign of World War I. "The Nek" was a narrow stretch of ridge on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The name derives from the Afrikaans word for a "mountain pass" but the terrain itself was a perfect bottleneck and easy to defend, as had been proven during an Ottoman attack in June. It connected Australian and New Zealand trenches on the ridge known as "Russell's Top" to the knoll called "Baby 700" on which the Ottoman defenders were entrenched.

The campaign on the Gallipoli Peninsula had begun in April 1915, but over the following months had developed into a stalemate. In an effort to break the deadlock, the British and their allies launched an offensive to capture the Sari Bair range. As part of this effort, a feint attack by Australian troops was planned at the Nek to support New Zealand troops assaulting Chunuk Bair.

Early on 7 August 1915, two regiments of the Australian 3rd Light Horse Brigade, one of the formations under the command of Major General Alexander Godley for the offensive, mounted a futile bayonet attack on the Ottoman trenches on Baby 700. Due to poor co-ordination and inflexible decision making, the Australians suffered heavy casualties for no gain. A total of 600 Australians took part in the assault, assaulting in four waves; 372 were killed or wounded. Ottoman casualties were negligible.

Prelude

[edit]Geography

[edit]A narrow saddle, the Nek connected the Australian and New Zealand trenches on Walker's Ridge at a plateau designated as "Russell's Top" (known as Yuksek Sirt to the Ottomans)[1] to the knoll called "Baby 700"[2] (Kilic Bayir),[3] on which the Ottoman defenders were entrenched in what the historian Chris Coulthard-Clark describes as "the strongest position at Anzac".[4] The immediate area was known to the British and Empire troops as the Anzac sector, and the allied landing site was dubbed Anzac Cove, after the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps.[5] The Nek was between 30–50 metres (98–164 ft) wide;[6] on each side, the ground sloped steeply down to deep valleys 150 metres (490 ft) below.[4] These valleys were Monash Valley to the south and Malone's Gulley to the north.[7][8]

The name given to the feature by Australian troops – the Nek – derives from the Afrikaans word for "mountain pass" and according to Glenn Wahlert was "likely coined by veterans of the South African war".[2] The Turkish name for the Nek was Cesarettepe.[9] It was well suited to defence, with no vegetation, and providing the defenders good observation and fields of fire along a narrow frontage.[2] The ground was bare and covered in pot-holes, and on a slight slope.[10] The difficult nature of the terrain had been highlighted earlier in the campaign, initially when a battalion of the Turkish 57th Regiment had suffered heavy casualties during a failed counter-attack in April.[11] After the 19 May Ottoman counter-attack, Major-General Alexander Godley had ordered an attack by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade across the Nek, but Brigadier General Andrew Russell (after whom Russell's Top was named) had convinced him to abandon this over concerns of the commanders of both the Wellington and Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiments.[12] Another unsuccessful attack resulting in heavy casualties had been made by the Turkish 18th Regiment across the Nek on the night of 30 June.[13] Despite these incidents, the challenges of attacking the Nek were not fully appreciated by Allied commanders when formulating the plan for the August Offensive.[14]

The Australian line at Russell's Top lay just below the Nek and extended 90 metres (300 ft). The right of the line lay opposite the Ottoman position across flat ground; it was described by Les Carlyon as a "conventional trench" and was deep enough that wooden hand and footholds had been attached to the wall of the trench to enable the assaulting troops to climb out. On the left of the Australian line, the line sloped away into dead ground where the Australians had established what Carlyon describes as a "ditch without a parapet" that was obscured from view with vegetation and earth.[15]

The Ottoman front line at the Nek consisted of two lines of trenches, with machine guns positioned on the flanks on spur lines, which provided clear fields of fire into no man's land in front of the Ottoman position.[16] Behind this another eight trenches existed, tiered along the slopes towards Baby 700. At least five groups of machine guns – approximately 30 altogether – were located in the area, providing direct fire support to the Ottoman troops holding the Nek.[17][18] These positions were widely dispersed and positioned in depth, at least 200 yards (180 m) from the Ottoman front line.[19] The commanders of the two Ottoman regiments occupying positions around the Nek had chosen not to cover their trenches, despite orders from their divisional headquarters, due to concerns that a bombardment would collapse the roofs and block communication through the trenches, similar to what had occurred at Lone Pine.[20]

Strategic situation and planning

[edit]For the three months since the 25 April landings, the Anzac beachhead had been a stalemate. On 19 May, Ottoman troops had attempted to break the deadlock with a counter-attack on Anzac Cove, but had suffered heavy casualties. In August, an Allied offensive (which later became known as the Battle of Sari Bair) was intended to break the deadlock by capturing the high ground of the Sari Bair range, and linking the Anzac front with a new landing to the north at Suvla. Along with the main advance north out of the Anzac perimeter, supporting attacks were planned from the existing trench positions.[21] Higher-level conceptual planning for the offensive was undertaken by the commander of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, Lieutenant General William Birdwood, and Colonel Andrew Skeen; more detailed tactical planning devolved to other staff.[22] Tactical command of the offensive to secure Sari Bair was given to Godley, who was at the time in command of the New Zealand and Australian Division.[23]

As part of the effort to secure Baby 700, Godley, assisted by Birdwood, planned a breakthrough from the Nek.[24] The official Australian historian Charles Bean writes that concerns about "attacking unaided" meant that plans were made to co-ordinate the attack with other actions.[25] The attack at the Nek was meant to coincide with an attack by New Zealand troops from Chunuk Bair, which was to be captured during the night. The light horsemen were to attack across the Nek to Baby 700 while the New Zealanders descended from the rear from Chunuk Bair onto Battleship Hill, the next knoll above Baby 700.[26][27] Other attacks were to be made by the 1st Light Horse Brigade at Pope's Hill and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade at Quinn's Post.[28]

The 3rd Light Horse Brigade was chosen for the attack at the Nek. This formation was commanded by Colonel Frederic Hughes, and consisted of the 8th, 9th and 10th Light Horse Regiments.[10] For the attack, the 8th and 10th would provide the assault troops, while the 9th was placed in reserve.[29] Some of its machine guns, positioned on Turk's Point, about 120 metres (390 ft) from the Nek, would provide direct fire support during the attack.[30] Like the other Australian Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles formations, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade had been dispatched to Gallipoli in May as infantry reinforcements, leaving their horses in Egypt.[31] The area around the Nek was held by the 18th Regiment,[32] under the command of Major Mustafa Bey. The regiment formed part of Mustafa Kemal's Ottoman 19th Division.[33][34] The 27th Regiment, under Lieutenant Colonel Sefik Bey, also held part of the line south from the Nek to Quinn's Post (Bomba Sirt).[35][36][9]

Godley's orders for the attack stipulated that the attack would be made with bayonets and grenades only; rifles would be unloaded.[37] This was, according to Roland Perry, designed to "influence the troopers to keep running at the [Ottoman] trenches" and ultimately meant they could not stop and fire.[24] Planners envisaged four waves of troops attacking from Russell's Top across the Nek. The first wave would use the cover of a naval bombardment to approach the trenches silently and quickly while the defenders were dazed, and would capture the trench with bayonets and grenades. The second wave would then pass through the first to capture trenches on the lower slopes of Baby 700. The third and fourth waves would exploit further and would dig-in,[10][37] with ultimate goal of securing the heights 200 metres (660 ft) away on Baby 700.[24] The British 8th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment, was to consolidate positions on the Nek afterwards, while two companies from the 8th Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers would advance up the western part of Monash Valley and carry out an attack around the "Chessboard" – to the south of the Nek[8] – to cover the southern flank of the Australians on the Nek.[38]

Preparations for the attack began several days earlier when the troopers were ordered to stow unnecessary clothing, including woollen tunics, and equipment. This resulted in the men living in the trenches for several cold nights in just shirts and short pants. Each man was authorised to carry 200 rounds of ammunition, as well as a small amount of personal rations. Assault equipment included wire cutters, empty sandbags, ladders, and periscopes; only the fourth and final assault line would carry entrenching tools.[24][39] The light horsemen had not participated in a large-scale attack before; they had not been trained to fight like infantrymen, having been recruited to fight in a mounted role, but they were all keen and eager for the attack to commence. Encouraged by earlier efforts by compatriots at Lone Pine, the troops were spurred on by the brigade major, Lieutenant Colonel John Antill, a Boer War veteran who encouraged them with stories from that war. Many soldiers who had been injured or ill, and were in hospital, ensured they were released and returned to their units in time to take part. In this climate, nobody questioned the tactics of the plan, contingencies, or the efficacy of attacking without loaded weapons.[40][41] Prior to the assault, each man was given a double issue of rum to warm up.[41]

Battle

[edit]The attack was scheduled to commence at 04:30 on 7 August.[42] It was to be preceded by a naval bombardment, supported by field guns from several shore based batteries.[43] The 8th and 10th Light Horse Regiments assembled in a trench about 90 metres (300 ft) long, opposite the Ottoman line that was between 20–70 metres (66–230 ft) away.[4][6] Coloured marker flags were carried, to be shown from the captured trenches to indicate success.[44] To help the supporting artillery to identify the attacking Australian troops, the attackers attached white armbands and patches to their shirts.[24][28]

On the morning of 7 August, it was clear that the prerequisites for the attack had not been met.[37][45] The initial concept of operations for the August offensive required a simultaneous attack from the rear of Baby 700, thereby creating a hammer and anvil effect on the Ottoman trenches caught in between this pincer movement.[46] Because the New Zealand advance on Chunuk Bair had been held up and failed to reach Chunuk Bair, the troops assaulting the Nek would have to do so alone if the attack was to continue.[42] The New Zealanders had made some progress, though, having captured the lower part of Rhododendron Spur and it was hoped that Chunuk Bair could still be carried; as a result, Birdwood and Skeen decided it was important for the attack on the Nek to proceed as a feint – rather than a pincer – to assist the New Zealanders at Chunuk Bair,[47][28] while the Australians and Indians from other formations also attacked Hill 971.[48] British troops were also landing at Suvla Bay, having commenced their operation the night before (6 August).[49]

A further part of the plan required an attack from Steele's Post through several tunnels against German Officers' Trench by the Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Bennett's 6th Battalion (2nd Infantry Brigade of the Australian 1st Division).[50] The Ottoman machine guns sited there enfiladed the ground in front of Quinn's Post and the Nek and the 6th Battalion's attack was conceived as a preliminary supporting move to suppress Ottoman fire onto the Nek to assist the 3rd Light Horse Brigade's. Planners had requested that this attack be conducted simultaneously with the attack at the Nek, but Birdwood had decided it should be conducted prior. The failure of this attack meant that Ottoman machine guns supporting the 18th Regiment around the Nek remained intact.[51] Nonetheless, Birdwood declared that the 3rd Light Horse Brigade's attack was to proceed, albeit with some modifications. This would see the Australian light horsemen become the right flank of the assault on Chunuk Bair, linking in with the New Zealand Infantry Brigade on Rhododendron Spur.[42]

Following the decision to proceed, at 04:00 field artillery and howitzers began firing from the beachhead around Anzac Cove onto the Ottoman trenches around the Nek. These guns were then joined by several warships, including a destroyer, which opened fire on the Nek and other positions around Baby 700. This continued at a steady and deliberate rate until 04:27, when the intensity rose. Due to the proximity of the two sides' trenches, the shells mostly landed behind the first line of Ottoman trenches.[52] Bean describes the bombardment as the heaviest since 2 May;[52] but Carlyon notes that no battleships were assigned to the shelling due to the proximity of the Australian trenches, and describes it as "'desultory' and a 'joke'", citing an officer from the 9th Light Horse Regiment, who were in reserve for the attack.[15]

According to Bean, owing to a failure to co-ordinate timings, the field artillery preparation of the forward positions ceased at 04:23, although the naval guns continued to engage some of the depth targets.[53] While the original plan had been for the attack to begin as soon as the artillery had stopped, local commanders did not adjust their plans following the early cutoff of preparatory fires and the attack was not launched until the appointed time of 04:30.[15][54] After the artillery firing ceased, no-one in the assaulting force knew if the bombardment was to continue. It was later discovered that the synchronisation of watches between the artillery officer and the assault officer was overlooked.[54] As the attack was not launched as soon as the bombardment ceased, but instead held back until the planned time of 04:30, the Ottoman defenders had ample time to return to their trenches – which were largely undamaged – and prepare for the assault that they now knew was coming.[15]

At the appointed time, the first wave of 150 men from the 8th Light Horse Regiment, led by their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Henry White, "hopped the bags" and went over the top.[55] They were met with a hail of machine gun and rifle fire and, within 30 seconds, White and all of his men were gunned down. A few men reached the Ottoman trenches, where they began to hurl grenades and marker flags were reportedly seen flying around the south-eastern corner of the Ottoman trench line, but the men were quickly overwhelmed by the Ottoman defenders.[56]

At this stage, the futility of the effort became clear to those in the second wave and, according to Carlyon, the attack should have been called off at this point.[57] The second wave of 150 followed the first without question two minutes later and met the same fate, almost all the men being cut down by heavy rifle and machine gun fire before they got halfway to the Ottoman trench.[44] This contrasted with the simultaneous attack by the 2nd Light Horse Regiment (1st Light Horse Brigade) at Quinn's Post, against the Ottoman trench system known as "The Chessboard", which was abandoned after 49 out of the 50 men in the first wave became casualties. In this case, the regiment's commander had not gone in the first wave and so was able to make the decision to cancel further attacks.[57][58]

As the third wave, consisting of men from the 10th Light Horse Regiment, began assembling in the forward trench, two Ottoman field artillery pieces began firing into no man's land.[59] Lieutenant Colonel Noel Brazier, commander of the 10th Light Horse Regiment, attempted to have the third wave cancelled. He was unable to find Hughes – who had moved to an observation post[60] – and instead found Antill. A strong personality, Antill exerted a large amount of influence within Hughes' command, and had a personal dislike of Brazier, who he felt was being insubordinate in questioning orders.[61][30] Antill had received the reports that marker flags, implying success, had been sighted.[62] This report of marker flags was subsequently confirmed in a Turkish article published after the war, where it was stated by the commander of the Turkish 27th Regiment that a couple of men with a marker flag reached the Ottoman trench and raised the flag, but were killed.[36] Antill had not checked the scene to establish if it was of any use to send the next wave,[61] nor did he confirm if the marker flags were still in place,[63] and after heated words with Brazier issued the order for the third wave to proceed without referring the matter to Hughes.[59] Without being able to speak to Godley, who was at his headquarters on the beach, Brazier returned to the forward Australian position at Russell's Top and gave the order for the third wave to attack,[64] telling them "Sorry, lads, but the order is to go".[59]

The assault by the third wave was launched at 04:45, and came to a quick end as before.[65][66] Brazier made another attempt to reason with Antill, as did the 10th Light Horse Regiment's second-in-command, Major Allan Love. Again Antill ordered the men forward. This time, Brazier conferred with several majors and then went forward to find Hughes, who called off the attack.[63] Meanwhile, the troops assigned to the fourth wave assembled on the fire-step of the forward Australian trench; amidst much confusion the right hand side of the line charged before Hughes' order could reach them. The troops on the left followed them shortly afterwards, but according to Bean many of them adopted a more cautious approach, "keeping low and not running".[67]

Briefly, Hughes entertained detaching a force via Monash Valley to support the British attack towards the "Chessboard" but this was eventually abandoned.[67] In the aftermath, the ridge between Russell's Top and the Turkish trenches was covered with dead and wounded Australian soldiers, most of whom remained where they fell for the duration of the war.[68] Recovering the wounded during the daylight proved largely impossible and many of those who lay injured on the battlefield succumbed in the intense heat. Some troops that had fallen into defiladed positions were recovered,[69] but mostly the wounded had to wait until night. Under the cover of darkness, stretcher bearers were able to venture out to recover some of the wounded, others of whom were able to crawl back to the Australian trenches.[70] A total of 138 wounded were saved.[71] Of these, one who had been wounded in the ankle made it back to Australian lines two nights later; he was among three men to have made it to the Ottoman firing line on the right. Another Australian, Lieutenant E.G. Wilson, is known to have reached the left trench where he was killed by an Ottoman grenade.[72]

Aftermath

[edit]

A further consequence of the failure to call off the attack at the Nek was that the supporting attack by two companies of the Royal Welch Fusiliers was launched from the head of Monash Valley, between Russell's Top and Pope's Hill, against the "Chessboard" trenches. Sixty-five casualties were incurred before the attack was aborted around 06:00.[73] The Australians charged with unloaded rifles with fixed bayonets and were unable to fire; in contrast the volume of fire they faced was, according to Bean, the most intense the Australians faced throughout the war.[74] Of the 600 Australians from the 3rd Light Horse Brigade who took part in the attack, the casualties numbered 372; 234 out of 300 men from the 8th Light Horse Regiment, of whom 154 were killed, and 138 out of the 300 men from the 10th, of whom 80 were killed. The Ottoman losses were negligible;[75] Bean notes that the Ottomans suffered no losses during the assault, but afterwards a "large number ... who continued to expose themselves after the attack ... were certainly shot by [Australian] machine guns" from Turk 's Point (to the north of Walker's Ridge and the Nek) and Pope's Hill (to the south).[76][8] Ottoman losses are placed at around twelve dead.[77]

In analysing the battle, Carlyon writes that the attack failed due to poor planning and appreciation of the ground by Birdwood, Godley and Skeen.[78] John Hamilton writes that in the aftermath, some Australians nicknamed the battleground "Godley's abattoir", holding him responsible for the losses.[79] Perry writes that Godley "on the beach and out of touch, was most culpable",[80] although Carlyon highlights command deficiencies within the Australian brigade as being a key factor, focusing on the role of Hughes and Antill in the decision to continue the attack.[61] Bean, while noting higher-level conceptual errors by Birdwood and Skeen, also concludes that the local commanders were "chiefly responsible" for the large-scale loss of life at the Nek.[81] Carlyon questions why Godley did not heed the lessons highlighted by the Ottoman attack over the same ground on 30 June, pointing out that the Australians were at several disadvantages – attacking up hill, in daylight and against stronger defences – compared to the Ottoman attack on 30 June. He also contrasts Hughes and Antill's unquestioning approach with that of Brigadier General Harold Walker, who was ordered to attack Lone Pine despite his own protests but who critically analysed the problem to give his soldiers the best chance of success.[82]

Bean wrote that the attack was "one of the bravest actions in the history of war",[83] but in terms of its wider impact, according to Carlyon the attack gained no ground and served no strategic purpose.[75] Coulthard-Clark concludes that "at most, the bold display by the light horsemen at the Nek may have impeded for a few hours – but did not prevent – the transfer of Turkish reinforcements towards Chunuk Bair, where the New Zealanders were also engaged in a desperate struggle".[45] Ultimately, the August Offensive failed to break the deadlock and it proved to be the last major attack launched by the Allied forces on the peninsula. Before it concluded, elements of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade – the 9th and 10th Light Horse Regiments – took part in another costly attack during the Battle of Hill 60.[84] As winter arrived in October, the Allies made plans to evacuate their troops from Gallipoli beginning in December 1915.[85] One of the final Allied offensive actions took place at the Nek during the evacuation when, on 20 December, a large mine was detonated under the Nek by Allied troops, killing 70 Ottoman defenders.[86]

Efforts were made by the Australians to recover their dead throughout the months following the battle, the 20th Battalion managing to recover the bodies of several men from the first wave, including White in October.[87] Most were unrecoverable during the campaign. When Australian Commonwealth burial parties returned to the peninsula in 1919 after the war's end, the bones of the dead light horsemen were still lying thickly on the small piece of ground. The Nek Cemetery now covers most of no-man's land of the tiny battlefield and contains the remains of 316 Australian soldiers, most of whom fell during the 7 August attack; only five could be identified.[88] Trooper Harold Rush of the 10th Light Horse Regiment died in the third wave. His body was one of the few identified, and he is buried in Walker's Ridge Cemetery. His epitaph famously reads: "His last words, Goodbye Cobber, God bless you".[63]

On 25 November 1915, shortly before the decision to completely withdraw from the peninsula, Godley was temporarily promoted to lieutenant general and appointed corps commander. After the evacuation (he left the day before the rest of his troops), in recognition of his services at Gallipoli, he was made Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, second highest of the seven British orders of chivalry.[89]

Post war, the belief that the main reason for the failure of the assault was due to a delay between the artillery bombardment and the attack being launched has been challenged. In 2017, author Graham Wilson discussed the delay at length, analysing various accounts of the assault. In doing so, he reached the conclusion that there are few accounts supporting the idea and opined that there had been no delay between the bombardment ending and the assault being launched. Instead, Wilson contends that reason for the high casualties amongst the attackers was likely due to the barrage itself being ineffective. He argues that due to the close proximity of the Allied and Ottoman trenches, the supporting artillerymen had likely been concerned about injuring the light horsemen forming up for the attack and had as such laid their guns behind the Ottoman forward defensive positions, meaning that when the assault began the troops in these lines were quickly able to return to their firing positions.[90]

Portrayals in media

[edit]In the aftermath of the battle, Bean covered the fighting at the Nek in a September 1915 article for The Argus that was heavily censored. A January 1916 report by the British commander during the Gallipoli campaign, General Ian Hamilton, provided limited details and was, according to Carlyon, very optimistic in its assessment. Godley's autobiography devoted only two sentences to the battle. Post-war, the battle formed the basis of a chapter in the second volume of Bean's official history.[91]

The battle is depicted in the climax of Peter Weir's movie, Gallipoli (1981),[92] although it inaccurately portrays the offensive as a diversion to reduce Ottoman opposition to the landing at Suvla Bay.[78] The battle is also depicted in the Gallipoli miniseries, episode 5: "The Breakout" (air date 2 March 2015).[93] The episode was reviewed for the Honest History website by Peter Stanley.[94]

References

[edit]- ^ Celik 2013, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Wahlert 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, p. xiii.

- ^ a b c Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 108.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, Map p. 60 & 191.

- ^ a b Perry 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Bean 1941a, p. 274.

- ^ a b c Burness 2013, Map p. 109.

- ^ a b Celik 2013, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Broadbent 2005, p. 203.

- ^ Wahlert 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 398.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 307–317.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, pp. 396–397 & 400.

- ^ a b c d Carlyon 2001, p. 403.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 464.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Perry 2009, p. 106.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 609.

- ^ Celik 2013, pp. 166–170.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, pp. 257–259.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 454.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d e Perry 2009, p. 104.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 597.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, Map p. 191 & 202.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 463–464.

- ^ a b c Burness 2013, p. 118.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, pp. 401 & 403.

- ^ a b Burness 2013, p. 119.

- ^ Bou 2010, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 307–317 & 611.

- ^ Celik 2013, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Broadbent 2013, p. 199.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, p. xiv.

- ^ a b Wahlert 2008, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Carlyon 2001, p. 401.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 608.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 610.

- ^ Perry 2009, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b Carlyon 2001, p. 402.

- ^ a b c Broadbent 2005, p. 202.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 611–612.

- ^ a b Bean 1941b, p. 615.

- ^ a b Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 109.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 464 & 597.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 597 & 607.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Burness 2013, p. 116.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 597–606.

- ^ a b Bean 1941b, p. 612.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 612–613.

- ^ a b Broadbent 2005, p. 204.

- ^ Burness 1990.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 613–615.

- ^ a b Carlyon 2001, p. 405.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 629–631.

- ^ a b c Carlyon 2001, p. 406.

- ^ Perry 2009, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Carlyon 2001, p. 410.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 617.

- ^ a b c Broadbent 2005, p. 207.

- ^ Perry 2009, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 618.

- ^ Perry 2009, p. 110.

- ^ a b Bean 1941b, p. 621.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, pp. 408 & 411.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 620.

- ^ Perry 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Broadbent 2005, p. 208.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 404.

- ^ Bean 1941b, pp. 621, 622 & 624.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 622.

- ^ a b Carlyon 2001, p. 408.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 624.

- ^ "Comprehensive list of Australian, British and Turkish Nek Killed in Action". Australian Light Horse Studies Centre. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ a b Carlyon 2001, p. 409.

- ^ Hamilton 2015, p. 112.

- ^ Perry 2009, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Bean 1941b, p. 631.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, p. 400.

- ^ Bean 1990, p. 109.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Fewster, Basarin & Basarin 2003, p. 125.

- ^ Hamilton 2015, p. 111.

- ^ "The Gallipoli Campaign, 1915" (PDF). Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ "No. 29507". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 March 1916. p. 2872.

- ^ Wilson 2017, Chapter 8.

- ^ Carlyon 2001, pp. 410–411.

- ^ "The Anzac Walk: The Nek". Visiting Gallipoli today. Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "ABC's Monday Closes In On Nine". TV Tonight. 3 March 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ Stanley, Peter (5 March 2015). "Scars breaking out on the Peninsh". Honest History. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Bean, Charles (1941a). The Story of ANZAC from the Outbreak of War to the End of the First Phase of the Gallipoli Campaign, May 4, 1915. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. I (11th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 220878987.

- Bean, Charles (1941b). The Story of ANZAC from May 4, 1915, to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. II (11th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 220898941.

- Bean, Charles (1990) [1948]. Gallipoli Mission. Sydney, New South Wales: Australian Broadcasting Corporation. ISBN 978-0-73330-022-6.

- Bou, Jean (2010). Light Horse: A History of Australia's Mounted Arm. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52119-708-3.

- Broadbent, Harvey (2005). Gallipoli: The Fatal Shore. Camberwell, Victoria: Viking/Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-04085-8.

- Broadbent, Harvey (2013). "Ottoman Commanders' Responses to the August Offensive". In Ekins, Ashley (ed.). Gallipoli: A Ridge Too Far. Wollombi, New South Wales: Exisle. pp. 196–213. ISBN 978-1-77559-051-4.

- Burness, Peter (1990). "White, Alexander Henry (1882–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. XII. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-52284-236-4.

- Burness, Peter (2013). "By Bomb and Bayonet". In Ekins, Ashley (ed.). Gallipoli: A Ridge Too Far. Wollombi, New South Wales: Exisle. pp. 106–125. ISBN 978-1-77559-051-4.

- Carlyon, Les (2001). Gallipoli. Sydney, New South Wales: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-74353-422-9.

- Celik, Kenan (2013). "There Will Be No Retreating: Turkish Soldiers' Reactions to the August Offensive". In Ekins, Ashley (ed.). Gallipoli: A Ridge Too Far. Wollombi, New South Wales: Exisle. pp. 162–179. ISBN 978-1-77559-051-4.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553227-9.

- Fewster, Kevin; Basarin, Vecihi; Basarin, Hatice Hurmuz (2003) [1985]. Gallipoli: The Turkish Story. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-045-5.

- Hamilton, John (2015). The Price of Valour: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Gallipoli Hero, Hugo Throssell, VC. Sydney, New South Wales: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-74261-336-9.

- Perry, Roland (2009). The Australian Light Horse. Sydney, New South Wales: Hachette Australia. ISBN 978-0-7336-2272-4.

- Wahlert, Glenn (2008). Exploring Gallipoli: An Australian Army Battlefield Guide. Australian Army Campaigns Series – 4. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Army History Unit. ISBN 978-0-9804753-5-7.

- Wilson, Graham (2017). Bully Beef & Balderdash. Volume II: More Myths of the AIF Examined and Debunked. London: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925520-32-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Burness, Peter (1996). The Nek: The Tragic Charge of the Light Horse at Gallipoli. Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-782-8.

- Broadbent, Harvey (2015). Defending Gallipoli: The Turkish Story. St. Leonards, New South Wales: Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-52286-457-1.

- Cameron, David (2009). Sorry, Lads, But the Order is to Go: The August Offensive, Gallipoli: 1915. Sydney, New South Wales: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-174223-077-1.

- Hamilton, John (2004). Goodbye Cobber, God Bless You. Sydney, New South Wales: Pan MacMillan Australia. ISBN 0-330-42202-2.

External links

[edit]- Celik, Kenan. "A Turkish View of the August Offensive". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "The Nek and Hill 60". Australian Light Horse Studies Centre. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- "The Nek – 7 August 1915". Australian Light Horse Studies Centre. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- "World War I Timeline – Gallipoli". University of San Diego History Department. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

40°14′29″N 26°17′18″E / 40.2414°N 26.288385°E