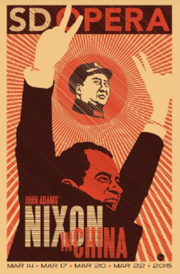

Nixon in China

| Nixon in China | |

|---|---|

| Opera by John Adams | |

2015 poster of the San Diego Opera | |

| Librettist | Alice Goodman |

| Language | English |

| Premiere | October 22, 1987 Wortham Theater Center, Houston |

| Website | www |

Nixon in China is an opera in three acts by John Adams with a libretto by Alice Goodman. Adams's first opera, it was inspired by U.S. president Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to the People's Republic of China. The work premiered at the Houston Grand Opera on October 22, 1987, in a production by Peter Sellars with choreography by Mark Morris. When Sellars approached Adams with the idea for the opera in 1983, Adams was initially reluctant, but eventually decided that the work could be a study in how myths come to be, and accepted the project. Goodman's libretto was the result of considerable research into Nixon's visit, though she disregarded most sources published after the 1972 trip.

To create the sounds he sought, Adams augmented the orchestra with a large saxophone section, additional percussion, and electronic synthesizer. Although sometimes described as minimalist, the score displays a variety of musical styles, embracing minimalism after the manner of Philip Glass alongside passages echoing 19th-century composers such as Wagner and Johann Strauss. With these ingredients, Adams mixes Stravinskian 20th-century neoclassicism, jazz references, and big band sounds reminiscent of Nixon's youth in the 1930s. The combination of these elements varies frequently, to reflect changes in the onstage action.

Following the 1987 premiere, the opera received mixed reviews; some critics dismissed the work, predicting it would soon vanish. However, it has been presented on many occasions since, in both Europe and North America, and has been recorded at least five times. In 2011, the opera received its Metropolitan Opera debut, a production based on the original sets, and in the same year was given an abstract production in Toronto by the Canadian Opera Company. Recent critical opinion has tended to recognize the work as a significant and lasting contribution to American opera.

Background

[edit]Historical background

[edit]

During his rise to power, Richard Nixon became known as a leading anti-communist. After he became president in 1969, Nixon saw advantages in improving relations with China and the Soviet Union; he hoped that détente would put pressure on the North Vietnamese to end the Vietnam War, and he might be able to manipulate the two main communist powers to the benefit of the United States.[1]

Nixon laid the groundwork for his overture to China even before he became president, writing in Foreign Affairs a year before his election: "There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation."[1] Assisting him in this venture was his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, with whom the President worked closely, bypassing Cabinet officials. With relations between the Soviet Union and China at a nadir—border clashes between the two took place during Nixon's first year in office—Nixon sent private word to the Chinese that he desired closer relations. A breakthrough came in early 1971, when Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong invited a team of American table tennis players to visit China and play against top Chinese players. Nixon followed up by sending Kissinger to China for clandestine meetings with Chinese officials.[1]

The announcement that Nixon would visit China in 1972 made world headlines. Almost immediately, the Soviet Union also invited Nixon for a visit, and improved US-Soviet relations led to the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT). Nixon's visit to China was followed closely by many Americans, and the scenes of him there were widely aired on television.[1] Chinese premier Zhou Enlai stated that the handshake he and Nixon had shared on the airport tarmac at the beginning of the visit was "over the vastest distance in the world, 25 years of no communication".[2] Nixon's change, from virulent anti-communist to the American leader who took the first step in improving relations with a great communist power, led to a new political adage, "Only Nixon could go to China."[1]

Inception

[edit]

In 1983, theater and opera director Peter Sellars proposed to American composer John Adams that he write an opera about Nixon's 1972 visit to China.[3] Sellars was intrigued by Nixon's decision to make the visit, seeing it as both "a ridiculously cynical election ploy ... and a historical breakthrough".[4] Adams, who had not previously attempted an opera, was initially skeptical, assuming that Sellars was proposing a satire.[5] Sellars persisted, however, and Adams, who had interested himself in the origin of myths, came to believe the opera could show how mythic origins may be found in contemporary history.[3] Both men agreed that the opera would be heroic in nature, rather than poking fun at Nixon or Mao.[6] Sellars invited Alice Goodman to join the project as librettist,[5] and the three met at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. in 1985 to begin intensive study of the six characters, three American and three Chinese, upon whom the opera would focus. The trio endeavored to go beyond the stereotypes about figures such as Nixon and Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao and to examine their personalities.[3]

As Adams worked on the opera, he came to see Nixon, whom he had once intensely disliked, as an "interesting character", a complicated individual who sometimes showed emotion in public.[7] Adams wanted Mao to be "the Mao of the huge posters and Great Leap Forward; I cast him as a heldentenor".[3] Mao's wife, on the other hand, was to be "not just a shrieking coloratura, but also someone who in the opera's final act can reveal her private fantasies, her erotic desires, and even a certain tragic awareness. Nixon himself is a sort of Simon Boccanegra, a self-doubting, lyrical, at times self-pitying melancholy baritone."[3]

Goodman explained her characterizations:

A writer tends to find her characters in her self, so I can tell you ... that Nixon, Pat, Mme. Mao, Kissinger and the chorus were all 'me.' And the inner lives of Mao and Chou En-Lai, who I couldn't find in myself at all, were drawn from a couple of close acquaintances.[8]

Sellars, who was engaged at the time in staging the three Mozart-Da Ponte operas, became interested in the ensembles in those works; this interest is reflected in Nixon in China's final act.[9] The director encouraged Adams and Goodman to make other allusions to classical operatic forms; thus the expectant chorus that begins the work, the heroic aria for Nixon following his entrance, and the dueling toasts in the final scene of Act 1.[9] In rehearsal, Sellars revised the staging for the final scene, changing it from a banquet hall in the aftermath of a slightly alcohol-fueled dinner to the characters' bedrooms.[10]

The work required sacrifices: Goodman later noted that choruses which she loved were dropped for the improvement of the opera as a whole. The work provoked bitter arguments among the three. Nevertheless, musicologist Timothy Johnson, in his 2011 book about Nixon in China, noted "the result of the collaboration betrays none of these disagreements among its creators who successfully blended their differing points of view into a very satisfyingly cohesive whole".[6]

Roles

[edit]| Role (and pinyin romanization)[11] | Voice type[11] | Premiere cast Houston, October 22, 1987 Conductor: John DeMain[12][13] |

|---|---|---|

| Richard Nixon | baritone | James Maddalena |

| Pat Nixon | soprano | Carolann Page |

| Chou En-lai (Zhou Enlai) | baritone | Sanford Sylvan |

| Mao Tse-tung (Mao Zedong) | tenor | John Duykers |

| Henry Kissinger | bass | Thomas Hammons |

| Chiang Ch'ing (Madame Mao) (Jiang Qing) | coloratura soprano | Trudy Ellen Craney |

| Nancy Tang (Tang Wensheng), First Secretary to Mao | mezzo-soprano | Mari Opatz |

| Second secretary to Mao | alto | Stephanie Friedman |

| Third secretary to Mao | contralto | Marion Dry |

| Dancers, militia, citizens of Peking | ||

Synopsis

[edit]- Time: February 1972.

- Place: In and around Peking.

Act 1

[edit]

At Peking Airport, contingents of the Chinese military await the arrival of the American presidential aircraft "Spirit of '76", carrying Nixon and his party. The military chorus sings the Three Rules of Discipline and Eight Points for Attention. After the aircraft touches down, Nixon emerges with Pat Nixon and Henry Kissinger. The president exchanges stilted greetings with the Chinese premier, Chou En-lai, who heads the welcoming party. Nixon speaks of the historical significance of the visit, and of his hopes and fears for the encounter ("News has a kind of mystery"). The scene changes to Chairman Mao's study, where the chairman awaits the arrival of the presidential party. Nixon and Kissinger enter with Chou, and Mao and the president converse in banalities as photographers record the scene. In the discussion that follows, the westerners are confused by Mao's gnomic and frequently impenetrable comments, which are amplified by his secretaries and often by Chou. The scene changes again, to the evening's banquet in the Great Hall of the People. Chou toasts the American visitors ("We have begun to celebrate the different ways") and Nixon responds ("I have attended many feasts"), after which the toasts continue as the atmosphere becomes increasingly convivial. Nixon, a politician who rose to prominence on anti-communism, announces: "Everyone, listen; just let me say one thing. I opposed China, I was wrong".

Act 2

[edit]

Pat Nixon is touring the city, with guides. Factory workers present her with a small model elephant which, she delightedly informs them, is the symbol of the Republican Party which her husband leads. She visits a commune where she is greeted enthusiastically, and is captivated by the children's games that she observes in the school. "I used to be a teacher many years ago", she sings, "and now I'm here to learn from you". She moves on to the Summer Palace, where in a contemplative aria ("This is prophetic") she envisages a peaceful future for the world. In the evening the presidential party, as guests of Mao's wife Chiang Ch'ing, attends the Peking Opera for a performance of a political ballet-opera The Red Detachment of Women. This depicts the downfall of a cruel and unscrupulous landlord's agent (played by an actor who strongly resembles Kissinger) at the hands of brave women revolutionary workers. The action deeply affects the Nixons; at one point Pat rushes onstage to help a peasant girl she thinks is being whipped to death. As the stage action ends, Chiang Ch'ing, angry at the apparent misinterpretation of the piece's message, sings a harsh aria ("I am the wife of Mao Tse-tung"), praising the Cultural Revolution and glorifying her own part in it. A revolutionary chorus echoes her words.

Act 3

[edit]On the last evening of the visit, as they lie in their respective beds, the chief protagonists muse on their personal histories in a surreal series of interwoven dialogues. Nixon and Pat recall the struggles of their youth; Nixon evokes wartime memories ("Sitting round the radio"). Mao and Chiang Ch'ing dance together, as the Chairman remembers "the tasty little starlet" who came to his headquarters in the early days of the revolution. As they reminisce, Chiang Ch'ing asserts that "the revolution must not end". Chou meditates alone; the opera finishes on a thoughtful note with his aria "I am old and I cannot sleep", asking: "How much of what we did was good?" The early morning birdcalls are summoning him to resume his work, while "outside this room the chill of grace lies heavy on the morning grass".

Performance history

[edit]The work was a joint commission from the Houston Grand Opera, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Netherlands Opera and the Washington Opera,[14] all of which planned to mount early productions of the opera.[12] Fearful that the work might be challenged as defamatory or not in the public domain, Houston Grand Opera obtained insurance to cover such an eventuality.[10] Before its stage premiere, the opera was presented in concert form in May 1987 in San Francisco, with intermission discussions led by Adams. According to the Los Angeles Times review, a number of audience members left as the work proceeded.[15]

Nixon in China formally premiered on the Brown Stage at the new Wortham Theater Center in Houston on October 22, 1987, with John DeMain conducting the Houston Grand Opera.[13] Former president Nixon was invited, and was sent a copy of the libretto; however, his staff indicated that he was unable to attend, due to illness and an impending publication deadline.[16] A Nixon representative later stated that the former president disliked seeing himself on television or other media, and had little interest in opera.[10] According to Adams, he was later told by former Nixon lawyer Leonard Garment that Nixon was highly interested in everything written about him, and so likely saw the Houston production when it was televised on PBS's Great Performances.[17]

The piece opened in conjunction with the annual meeting of the Music Critics Association, guaranteeing what the Houston Chronicle described as a "very discriminating audience".[18] Members of the association also attended meetings with the opera's production team.[18] When Carolann Page, originating Pat Nixon, waved to the audience in character as First Lady, many waved back at her.[19] Adams responded to complaints that the words were difficult to understand (no supertitles were provided) by indicating that it is not necessary that all the words be understood on first seeing an opera.[16] The audience's general reaction was expressed by what the Los Angeles Times termed "polite applause", the descent of the Spirit of '76 being the occasion for clapping from both the onstage chorus and from the viewers in the opera house.[20]

When the opera reached the Brooklyn Academy of Music, six weeks after the world premiere, there was again applause during the Spirit of '76's descent. Chou En-lai's toast, addressed by baritone Sanford Sylvan directly to the audience, brought what pianist and writer William R. Braun called "a shocked hush of chastened admiration".[4] The meditative Act 3 also brought silence, followed at its conclusion by a storm of applause.[4] On March 26, 1988, the work opened at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, where Nixon's emergence from the plane was again met with applause.[21]

After the opera's European premiere at the Muziektheater in Amsterdam in June 1988, it received its first German performance later that year at the Bielefeld Opera, in a production by John Dew with stage designs by Gottfried Pilz.[22] In the German production, Nixon and Mao were given putty noses in what the Los Angeles Times considered "a garish and heavy-handed satire".[10] Also in 1988 the opera received its United Kingdom premiere, at the Edinburgh International Festival in August.[23]

For the Los Angeles production in 1990, Sellars made revisions to darken the opera in the wake of the Tiananmen Square protests. The original production had not had an intermission between Acts 2 and 3; one was inserted, and Sellars authorized supertitles, which he had forbidden in Houston.[10] Adams conducted the original cast in the French premiere, at the Maison de la Culture de Bobigny, Paris, on December 14, 1991.[24] Thereafter, performances of the opera became relatively rare; writing in The New York Times in April 1996, Alex Ross speculated on why the work had, at that time, "dropped from sight".[25]

The London premiere of the opera took place in 2000, at the London Coliseum, with Sellars producing and Paul Daniel conducting the English National Opera (ENO).[26] A revival of this production was planned for the reopening of the renovated Coliseum in 2004, but delays in the refurbishment caused the revival to be postponed until 2006.[27] The ENO productions helped to revive interest in the work, and served as the basis of the Metropolitan Opera's 2011 production.[28] Peter Gelb, the Met's general manager, had approached Adams in 2005 about staging his operas there. Gelb intended that Nixon in China be the first of such productions, but Adams chose Doctor Atomic to be the first Adams work to reach the Met.[29] However, Gelb maintained his interest in staging Nixon in China, which received its Metropolitan premiere on February 2, 2011.[30] The work received its BBC Proms debut at the Royal Albert Hall in London on September 5, 2012, although the second-act ballet was omitted.[31]

While a number of productions have used variations on the original staging, the February 2011 production by the Canadian Opera Company used an abstract setting revived from a 2004 production by the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis.[8] Alluding to Nixon's "News" aria, the omnipresence of television news was dramatized by set designer Allen Moyer by keeping a group of televisions onstage throughout much of the action, often showing scenes from the actual visit. Instead of an airplane descending in Act 1, a number of televisions descended showing an airplane in flight.[32]

Adams conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Los Angeles Master Chorale for performances of the opera at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2017 during a series of concerts celebrating his 70th birthday. This "musically and visually dazzling reimagining of the piece" [33] included Super 8mm home movies of the visit to China (shot by H. R. Haldeman, Dwight Chapin, and others) projected onto a giant screen with the appearance of a 1960s television set. In some scenes the historical footage was a backdrop that was artfully synchronized to the live cast in the foreground, in other scenes the actors were lit from behind the translucent screen appearing inside the TV, adding to the surreal experience. The props and other details were simple but effective, including the miniature souvenir program designed after Mao's Little Red Book.

Despite a recent proliferation of performances worldwide, the opera has not been shown in China as of 2011[update].[8]

Houston Grand Opera is again producing the opera in 2017 on the 30th anniversary of the world premiere to mixed reviews.[34][35][36]

A new production was premiered at Staatsoper Stuttgart in April 2019.

Reception

[edit]

The original production in Houston received mixed reviews. Chicago Tribune critic John von Rhein called Nixon in China "an operatic triumph of grave and thought-provoking beauty".[8] Houston Chronicle reviewer Ann Holmes said of the work, "The music of Nixon catches in your ear; I find myself singing it while whizzing along the freeways."[37] Los Angeles Herald Examiner critic Mark Swed wrote that it would "bear relevance for as long as mankind cherished humanity".[8] Martin Bernheimer, writing in the Los Angeles Times, drew attention to the choreography of Morris ("the trendy enfant terrible of modern dance") in the Act 2 ballet sequences. Morris had produced "one of those classical yet militaristic Sino-Soviet ballets from the revolutionary repertory of Mme. Mao". Bernheimer also praised "the subtle civility of Alice Goodman's couplet-dominated libretto".[20]

In a more critical vein, The New York Times chief music critic Donal Henahan alluded to the publicity buildup for the opera by opening his column, headed "That was it?", by calling the work "fluff" and "a Peter Sellars variety show, worth a few giggles but hardly a strong candidate for the standard repertory".[8] New York magazine Peter G. Davis said that "Goodman's libretto, written in elegant couplets, reads better than it sings" and "the main trouble... is Adams's music... this is the composer's first opera and it shows, mainly in the clumsy prosody, turgid instrumentation that often obscures the words, ineffective vocal lines, and inability to seize the moment and make the stage come to life."[38] St. Louis Post-Dispatch critic James Wierzbicki called the opera "more interesting than good ... a novelty, not much more."[16] Television critic Marvin Kitman, just prior to the telecast of the original Houston production in April 1988, stated "There are only three things wrong with Nixon in China. One, the libretto; two, the music; three, the direction. Outside of that, it's perfect."[8]

The critic Theodore Bale, in his review of a revival of the opera in Houston in 2017, said he continues "to enjoy being perplexed by its deep structure and quirky contemporary aesthetic. Adam's music is constantly shimmering with some new idea, Alice Goodman's libretto is constantly surprising and eloquent, and each of the three acts offers myriad opportunities for interpretation and commentary. The opera is filled with gorgeous ensemble passages and the chorus as an entity is at the heart of the work. I have, I suppose, "used" Nixon in China for three decades as one of the finest examples of late 20th-century American opera."[39]

The British premiere at the 1988 Edinburgh Festival brought critical praise: "Through its sheer cleverness, wit, lyrical beauty and sense of theater, it sweeps aside most of the criticism to which it lays itself open."[40] When the work was finally performed in London, 13 years after its Houston premiere and after a long period of theatrical neglect, Tempo's critic Robert Stein responded to ENO's 2000 production enthusiastically. He particularly praised the performance of Maddalena, and concluded that "Adams's triumph ... consists really in taking a plot chock-full of talk and public gesture, and through musical characterisation ... making a satisfying and engaging piece."[26] Of the ENO revival in 2006, Erica Jeal of The Guardian wrote that "from its early visual coup with the arrival of the plane, Sellars' production is an all-too-welcome reminder of his best form". In Jeal's view, the cast met admirably the challenge of presenting the work in a non-satirical spirit.[27] Reviewing the 2008 Portland Opera production (the basis of the 2011 Canadian Opera Company presentation in Toronto), critic Patrick J. Smith concluded that "Nixon in China is a great American Opera. I suspected that it was a significant work when I saw it in 1987; I was ever more convinced of its stature when I heard it subsequently, on stage and on disc, and today I am certain that it is one of the small handful of operas that will survive."[41]

At the Met premiere in February 2011, although the audience—which included Nixon's daughter Tricia Nixon Cox—gave the work a warm reception,[28] critical approval of the production was not uniform. Robert Hofler of Variety criticized Sellars for using body microphones to amplify the singing, thus compensating for the "vocally distressed" Maddalena. He further complained that the director, known for designing unorthodox settings for the operas he has staged (Hofler mentions The Marriage of Figaro in the New York Trump Tower and Don Giovanni in an urban slum), here uses visually uninteresting, overly realistic sets for the first two acts. Hofler felt that it was time that the opera received a fresh approach: "Having finally arrived at the Met, Nixon in China has traveled the world. It is a masterpiece, a staple of the opera repertory, and now it simply deserves a new look".[42] However, Anthony Tommasini of The New York Times, while noting that Maddalena's voice was not as strong as it had been at the world premiere, maintained that due to his long association with the role, it would have been impossible to bring the opera to the Met with anyone else as Nixon: "Maddalena inhabits the character like no other singer".[28] Tommasini also praised the performance of Robert Brubaker in the role of Mao, "captur[ing] the chairman's authoritarian defiance and rapacious self-indulgence", and found the Scottish soprano Janis Kelly "wonderful" as Pat Nixon.[28]

Swed recalled the opera's reception in 1987 while reviewing the Metropolitan Opera's 2011 production:

An opera that was belittled in 1987 by major New York critics – as a CNN Opera of no lasting merit when Houston Grand Opera premiered it – has clearly remained relevant. Reaching the Met for the first time, it is now hailed as a classic.[43]

Music

[edit]Nixon in China contains elements of minimalism. This musical style originated in the United States in the 1960s and is characterized by stasis and repetition in place of the melodic development associated with conventional music.[44] Although Adams is associated with minimalism, the composer's biographer, Sarah Cahill, asserts that of the composers classed as minimalists, Adams is "by far the most anchored in Western classical tradition".[45]

Timothy Johnson contends that Nixon in China goes beyond minimalism in important ways. Adams had been inspired, in developing his art, by minimalist composers such as Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and Terry Riley, and this is reflected in the work by repetitive rhythmic patterns. However, the opera's complex harmonic structures are very different from the simpler ones in, for example, Glass's Einstein on the Beach, which Adams terms "mindlessly repetitive"; Johnson nevertheless considers the Glass opera an influence on Nixon in China.[46] As Glass's techniques did not allow Adams to accomplish what he wanted, he employed a system of constantly shifting metric organizational schemes to supplement the repeated rhythms in the opera. The music is marked by metrical dissonance, which occurs both for musical reasons and in response to the text of the opera.[47]

The New York Times critic Allan Kozinn writes that with Nixon in China, Adams had produced a score that is both "minimalist and eclectic ... In the orchestral interludes one hears references, both passing and lingering, to everything from Wagner to Gershwin and Philip Glass."[48] In reviewing the first recording of the work, Gramophone's critic discusses the mixture of styles and concludes that "minimalist the score emphatically is not".[49] Other commentators have evoked "neo-classical Stravinsky",[50] and concocted the term "Mahler-meets-minimalism", in attempts to pinpoint the opera's idiom.[51]

The opera is scored for an orchestra without bassoons, French horns, and tuba, but augmented by saxophones, pianos, and electronic synthesizer. The percussion section incorporates numerous special effects, including a wood block, sandpaper blocks, slapsticks and sleigh bells.[52] The work opens with an orchestral prelude of repetitive ascending phrases, after which a chorus of the Chinese military sings solemn couplets against a subdued instrumental background. This, writes Tommasini, creates "a hypnotic, quietly intense backdrop, pierced by fractured, brassy chords like some cosmic chorale", in a manner reminiscent of Philip Glass.[28] Tommasini contrasts this with the arrival of Nixon and his entourage, when the orchestra erupts with "big band bursts, rockish riffs and shards of fanfares: a heavy din of momentous pomp".[28] Gramophone's critic compares the sharply written exchanges between Nixon, Mao and Chou En-lai with the seemingly aimless wandering of the melodic lines in the more reflective sections of the work, concluding that the music best serves the libretto in passages of rapid dialogue.[49] Tommasini observes that Nixon's own vocal lines reflect the real-life president's personal awkwardness and social unease.[28][48]

The differences in perspective between East and West are set forth early in the first act, and underscored musically: while the Chinese of the chorus see the countryside as fields ready for harvest, the fruits of their labor and full of potential, the Nixons describe what they saw from the windows of the Spirit of '76 as a barren landscape. This gap is reflected in the music: the chorus for the workers is marked by what Johnson terms "a wide-ranging palette of harmonic colors", the Western perspective is shown by the "quick, descending, dismissive cadential gesture" which follows Nixon's description of his travels.[53]

The second act opens with warm and reflective music culminating in Pat Nixon's tender aria "This is prophetic". The main focus of the act, however, is the Chinese revolutionary opera-ballet, The Red Detachment of Women, "a riot of clashing styles" according to Tommasini, reminiscent of agitprop theatre with added elements of Strauss waltzes, blasts of jazz and 1930s Stravinsky.[28][49] The internal opera is followed by a monologue, "I am the wife of Mao Tse-tung" in which Chiang Ch'ing, Mao's wife, rails against counterrevolutionary elements in full coloratura soprano mode that culminates in a high D, appropriate for a character who in real life was a former actress given to self-dramatization.[a] Critic Thomas May notes that, in the third act, her "pose as a power-hungry Queen of the Night gives way to wistful regret".[9] In this final, "surreal" act[55] the concluding thoughts of Chou En-lai are described by Tommasini as "deeply affecting".[28] The act incorporates a brief foxtrot episode, choreographed by Morris, illustrating Pat Nixon's memories of her youth in the 1930s.[55][b]

Critic Robert Stein identifies Adams's particular strengths in his orchestral writing as "motoring, brassy figures and sweetly reflective string and woodwind harmonies",[26] a view echoed by Gregory Carpenter in the liner notes to the 2009 Naxos recording of the opera. Carpenter pinpoints Adams's "uncanny talent for recognising the dramatic possibilities of continually repeating melodies, harmonies and rhythms", and his ability to change the mix of these elements to reflect the onstage action.[58] The feel of the Nixon era is recreated through popular music references;[59] Sellars has observed that some of the music associated with Nixon is derived from the big band sound of the late 1930s, when the Nixons fell in love.[3] Other commentators have noted Adams's limitations as a melodist,[49] and his reliance for long stretches on what critic Donal Henahan has described as "a prosaically chanted recitative style".[60] However, Robert Hugill, reviewing the 2006 English National Opera revival, found that the sometimes tedious "endless arpeggios" are often followed by gripping music which immediately re-engages the listener's interest.[61] This verdict contrasts with that of Davis after the original Houston performance; Davis commented that Adams's inexperience as an opera writer was evident in often "turgid instrumentation", and that at points where "the music must be the crucial and defining element ... Adams fails to do the job".[38]

List of arias and musical sequences

[edit]|

Act 1

|

Act 2

|

Act 3

|

Recordings

[edit]The opera has been recorded at least six times:

| Year | Details | Roles | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conductor | Chiang | Pat | Mao | Chou | Nixon | Kissinger | |||||

| 1987 | Filmed Oct. 1987 in Houston for a PBS Great Performances broadcast | DeMain | Craney | Page | Duykers | Sylvan | Maddalena | Hammons | |||

| 1987 | Recorded Dec. 1987 in RCA Studio A, New York for 3-CD set on Nonesuch | de Waart | Craney | Page | Duykers | Sylvan | Maddalena | Hammons | |||

| 2008 | Recorded live in Denver for 3-CD set on Naxos[62][63] | Alsop | Dahl | Kanyova | Heller | Yuan | Orth | Hammons | |||

| 2011 | Filmed in New York for Nonesuch DVD[64] | Adams | Kim-K | Kelly | Brubaker | Braun | Maddalena | Fink | |||

| 2012 | Filmed in Paris for Mezzo TV | Briger | Jo | Anderson-J | Kim-A | Kim-KC | Pomponi | Sidhom | |||

| 2023 | Filmed on April 7, 2023 in Paris for Mezzo TV and medici.tv[65] | Dudamel | Kim | Fleming | Myers | Zhang | Hampson | Bloom | |||

The only studio recording, made in New York by Nonesuch two months after the October 1987 Houston premiere, used the same cast, just a different chorus, orchestra and conductor: Edo de Waart led the Chorus and Orchestra of St. Luke's. Gramophone's Good DVD Guide praised the singing, noting James Maddalena's "aptly volatile Nixon" and Trudy Ellen Craney's admirable delivery of Chiang Ch'ing's coloratura passages.[66] This recording also received the 1988 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Composition in the Classical category.[67] It was reissued in 2011 to coincide with the opera's production at the Metropolitan Opera.[62] The Denver live recording on Naxos has Marin Alsop conducting the Colorado Symphony and Opera Colorado Chorus, with Robert Orth as Nixon, Maria Kanyova as Pat Nixon, Thomas Hammons as Kissinger, Chen-Ye Yuan as Chou En-Lai, Marc Heller as Mao Tse-Tung and Tracy Dahl as Chiang Ch'ing.[58] Sumi Jo and June Anderson star as the two wives in the Paris video.

References

[edit]- ^ "Several of the solos are direct descendants of 19th-century Italian opera archetypes: Chiang Ch'ing's bravura aria at the end of Act II ('I am the wife of Mao Tse-tung'), for example, contains coloratura runs up to a high D—a 'showpiece' aria for a character whose capacity for self-dramatization (as a former actress) was an important facet of her personality".[54]

- ^ As "a kind of warmup for embarking on the creation of the full opera", Adams had written an extended orchestral foxtrot, The Chairman Dances.[56] Although this was not incorporated into the opera it is performed regularly as a concert piece, and has been fashioned by choreographer Peter Martins into a ballet.[57]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e "Foreign Affairs". American President: Richard Milhous Nixon (1913–1994). Miller Center for Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ Kabaservice, Ch. 11 (unpaginated).

- ^ a b c d e f "The Myth of History". The Metropolitan Opera Playbill (Nixon in China Edition): 6–10. February 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c Braun, William R. (February 2011). "The Inquiring Mind". Opera News: 20–24.

- ^ a b Park, Elena. "History in the making". John Adams's Nixon in China. Metropolitan Opera. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Johnson, p. 3.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (February 2, 2011). "Adams/Nixon: A kitchen debate on portraying a president in opera". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2024. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gurewitsch, Matthew (January 26, 2011). "Still Resonating From the Great Wall". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c May, Thomas (February 9, 2011). "Program Note". The Metropolitan Opera Playbill (Nixon in China Edition): Ins1–Ins3.

- ^ a b c d e Henken, John (September 2, 1990). "Rethinking Nixon in China". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2024-01-02. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ a b "Nixon in China". Opera News: 38. February 2011.

- ^ a b von Rhein, John (October 30, 1987). "DeMain earns praise conducting new Nixon opera". Chicago Tribune via The Vindicator (Youngstown, Ohio). Archived from the original on September 1, 2024. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Holmes, Ann (October 18, 1987). "Nixon in China/HGO presents world premiere of unusual opera". Houston Chronicle. p. Zest 15. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (July 28, 1987). "International network nourishes avant-garde". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 23, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Bernheimer, Martin (May 25, 1987). "Minimalist Mush : Nixon Goes To China Via Opera In S.f". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c Ward, Charles (October 24, 1987). "'Critics review Wortham, Nixon opera". Houston Chronicle. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Johnson, p. 4.

- ^ a b "Classical music critics gather here for meeting". Houston Chronicle. October 22, 1987. p. 7. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Ewing, Betty (October 24, 1987). "Dancing lions greet Nixon in Houston". Houston Chronicle. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Bernheimer, Martin (October 24, 1987). "Gala opera premiere: John Adams' Nixon in China in Houston". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ "James Maddalena, baritone". CA Management. Archived from the original on 2016-08-11. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Neef, Sigrid, ed. (2000). Opera: Composers, Works, Performers (English ed.). Cologne: Könemann. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-3-8290-3571-2.

- ^ "Edinburgh International Festival". The Scotsman. March 27, 2010. Archived from the original on September 1, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Nixon in China". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ^ Ross, Alex (April 7, 1996). "Nixon Is Everywhere, it Seems, but in 'China'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c Stein, Robert (2000). "London Coliseum: Nixon in China". Tempo (214): 43–45. JSTOR 946494. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Jeal, Erica (June 19, 2006). "Nixon in China". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 1, 2024. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tommasini, Anthony (February 3, 2011). "President and Opera, on Unexpected Stages". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Gelb, Peter (February 9, 2011). "Nixon lands at the Met". The Metropolitan Opera Playbill (Nixon in China Edition): 3.

- ^ "Nixon in China: The Background". Opera News: 40. February 2011.

- ^ Ashley, Tim (September 6, 2012). "Prom 72: Nixon in China—review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 1, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Everett-Green, Robert (February 7, 2011). "Nixon in China fuses national and personal histories". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Ginell, Richard (4 March 2017). "L.A. Phil delivers a dazzling reimagining of 'Nixon in China'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "Houston Grand Opera's 2016–17 Season ... Celebrates 30th Anniversary of HGO World Premiere of John Adams's Nixon in China (PDF)" (PDF) (Press release). Houston Grand Opera. January 29, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ "HGO's rousing Nixon in China sheds new light on an American masterpiece". CultureMap Houston. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved Jun 10, 2020.

- ^ Chen, Wei-Huan (Jan 23, 2017). "'Nixon in China' can't hide behind art to avoid social responsibility". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved Jun 10, 2020.

- ^ Holmes, Ann (November 1, 1987). "After the ball/With the frenzy of three simultaneous operas behind it, what's next for the HGO?". Houston Chronicle. p. Zest p. 23.

- ^ a b Davis, Peter G. (November 9, 1987). "Nixon—the opera". New York: 102–104. Archived from the original on September 1, 2024. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "HGO's rousing Nixon in China sheds new light on an American masterpiece" Archived 2017-01-26 at the Wayback Machine by Theodore Bale, Culturemap Houston, January 24, 2017

- ^ Ward, Charles (September 6, 1988). "British critics laud Nixon in China". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Patrick J. (2005). "Nixon in China: A Great American Opera". Portland Opera. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ^ Hofler, Robert (February 3, 2011). "Nixon in China". Variety. Archived from the original on March 25, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Swed, Mark (February 13, 2011). "Opera review: 'Nixon in China' at the Metropolitan Opera". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Davis, Lucy (2007). "Minimalism". Oxford Companion to Music (online edition). Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ Cahill, Sarah (2007). "Adams, John (Coolidge)". Oxford Music Online. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ Johnson, p. 7.

- ^ Johnson, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Kozinn, Allan (2007). "Nixon in China". Oxford Music Online. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c d "Adams: Nixon in China". Gramophone: 148. October 1988. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Oestreich, James R. (June 17, 2008). "The Nixonian Psyche, With Arias and a Bluish Glow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Mellor, Andrew (December 21, 2009). "You hear the machinery of Adams's writing: bright, alert, lucid". BBC. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "John Adams – Nixon in China". Boosey & Hawkes. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- ^ Johnson, p. 22.

- ^ "In Focus". The Metropolitan Opera Playbill (Nixon in China Version): 33–34. February 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Yohalem, John (February 7, 2011). "Nixon in China, New York". Opera Today. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Adams, John (23 September 2003). "The Chairman Dances: Foxtrot for orchestra (1985)". John Adams official website. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ Kisselgoff, Anna (May 16, 1988). "Ray Charles at a Peter Martins City Ballet Premiere". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Carpenter, Gregory (2008). American Opera Classics: Nixon in China (CD). Naxos Records. (liner notes, pp. 5–6)

- ^ "Adams in China". Gramophone: 12. October 1998. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Henahan, Donal (October 24, 1987). "Opera: Nixon in China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Hugill, Robert (July 2, 2006). "A Mythic Story". Music & Vision. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "John Adams: Nixon in China". Nonesuch Records. 15 April 1988. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Adams, John. "Nixon in China, Nonesuch CD". Discog. Archived from the original on 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "Nixon in China [Blu-ray/DVD] | Nonesuch Records - MP3 Downloads, Free Streaming Music, Lyrics". Nonesuch Records Official Website. 2012-10-03. Archived from the original on 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Blum, Ronald (27 March 2023). "Fleming stars as 'Nixon in China' arrives at Paris Opera". AP News. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Roberts, David, ed. (2006). The Classical Good CD and DVD Guide. London: Haymarket. ISBN 978-0-86024-972-6.

- ^ "Past Winners Search". Grammy.com. The Recording Academy. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

Other sources

- Johnson, Timothy A. (2011). John Adams's Nixon in China: Musical Analysis, Historical and Political Perspectives. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4094-2682-0.

- Kabaservice, Geoffrey (2012). Rule and Ruin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199912902.

External links

[edit]- Nixon in China from John C. Adams's official website

- 1987 operas

- English-language operas

- Opera world premieres at Houston Grand Opera

- Minimalist operas

- Operas

- Operas set in the 20th century

- Operas by John Adams (composer)

- Operas set in China

- Cultural depictions of Richard Nixon

- Cultural depictions of Henry Kissinger

- Cultural depictions of Mao Zedong

- Cultural depictions of Zhou Enlai

- Works about Richard Nixon

- Operas based on real people

- Operas about politicians

- Beijing in fiction